Discover more from Adrian’s Newsletter

As a classroom teacher, I have always strived to try new things. I redesign my lesson plans, my classroom layout, and my delivery of instruction. I’m constantly trying to find what works best for my students. It’s an elusive goal: What works one day, oftentimes doesn’t work the next; each new group has different strengths, challenges, personalities, and educational needs. When I first learned about project-based learning in 2015, I thought, Hey! That’s what I do in my classroom! I never called it PBL, but each year, I tried to be more interdisciplinary. I tried to tie what we were learning with the real world. I would find great problems for my students to solve connected to what we were learning in each content area.

Solving real-world problems was great for helping my students learn team dynamics, design thinking, and collaboration. However, I found that sometimes, the problems I was using were not authentic to my students. I wanted them to help me find relevant problems that we could solve together. I didn’t want to always be the one finding projects and problems. I didn’t want students making posters and dioramas just because. Loni Bergqvist, PBL Instructor and Founder of Imagine If, puts it beautifully.

Products ARE the learning if products NEED the learning.

— Loni Bergqvist

Did all of my final products need the learning we were doing? Bergqvist believes that it's “through making products that we really learn because we are actively applying knowledge.” Were my students really applying their new knowledge? Having students complete a craft can be a creative endeavor; however not all crafts are creative. Crafts that are connected to non-authentic problems may be fun, but are most likely structured solely for the purpose of assigning a grade or encouraging student compliance. They can be used to trick students into thinking they are participating in an engaging and rigorous experience. Even if I framed my projects with an open-ended question, the onus of control was still with me. I decided the question. I decided the project. I decided the timeline. I decided the measures for success. I decided the grades.

Finding meaningful problems and authentic projects for my students was hard.

Ewan McIntosh, founder of NoTosh, discusses that many of our public schools are “crazy about problem-based learning, but they’re obsessed with the wrong bit of it. While everyone looks at how we could help young people become better problem-solvers, we’re not thinking how we could create a generation of problem finders.” He describes a story related to him by Alan November, an educator specializing in educational technology. In it, Alan tells about teaching a Community Problem Solving course “where, on the first day, he set students the task of finding a problem in the local community that they could then go off and solve using whatever technology they had available. From the front row, a hand shot up. ‘Mr. November?’ began one of the girls in the class. ‘You’re the teacher, we’re the students. It’s your job to come up with the problems and give them to us to solve. This was in 1983.” How is this possible? Tony Wagner, author of Creating Innovators: The Making of Young People Who Will Change the World, believes that the answer is a direct result of years of pedagogical practice where “the academic world sees its mission as creating and transmitting ‘pure’ knowledge, divorced from any kind of application or the development of specific skills.”

I don’t want my classroom to be structures as a knowledge factory, but as a vibrant, collaborative think tank, where everyone involved is simultaneously searching for interesting and relevant problems to solve and designing creative solutions to those problems. Tim Brown, the CEO of IDEO, defines this type of design thinking system as “a human-centered approach to innovation that draws from the designer’s toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success.” I don’t want to view my students a group of kids with separate creative ideas, but as a collection of innovative problem solvers. I do not want compliance, even if it means a cool final project or craft. I want to enhance my students’ creativity, not just give them something creative to do.

I began searching for frameworks that would help me structure my thinking, while giving me language that I could share with my colleagues. I didn’t want Pinterest crafts or preplanned activities. I didn’t want buzzwords. I wanted concrete pedagogy that I could apply to designing better learning experiences for my students.

The Frameworks

There are so many PBL frameworks on the Internet. I started by studying the famed PBL-focused High Tech High (HTH) in San Diego, California. If I could do a fraction of what they do, it would be incredible! HTH started as a single charter school in 2000. It has has since grown into an integrated network of sixteen charter schools serving approximately 6,350 students in grades K-12 across four campuses. They are student-centered and PBL-focused, with some amazing final products. Their model is that “learning is personalized, competency based, takes place anytime/anywhere, and students exert ownership over their learning.” Since I wasn’t planning to work at HTH, I kept looking for frameworks I could apply to my planning, teaching, and assessment. I discovered George Couros, Dr. Tina Seelig, and John Spencer.

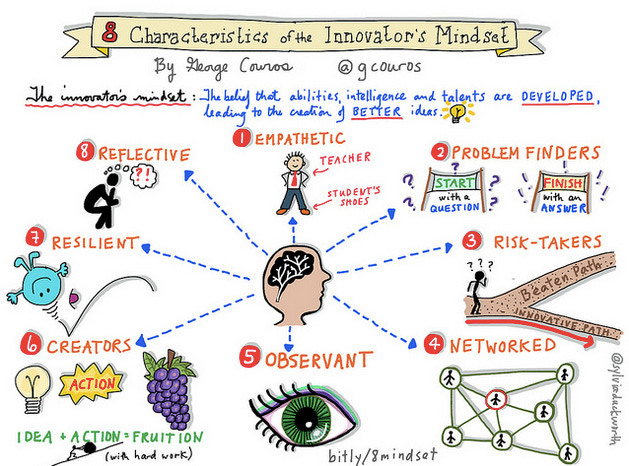

George Couros used Carol Dweck’s Growth Mindset to create his Innovator’s Mindset. He describes the importance of eight characteristics for students to have when being innovative: (a) empathetic; (b) problem finders; (c) risk-takers; (d) networked; (e) observant; (f) creators; (g) resilient; (h) reflective. Notice that being a problem finder is an important characteristic of creativity and innovation.

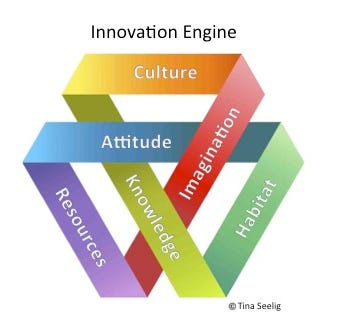

Dr. Tina Seelig views creativity as an imperative life skill. She believes that creativity is “an endless renewable resource [that anyone] can tap into at any time.” Her Innovation Engine takes into consideration the complex nature of creativity and how it is influenced by many factors. For example, knowledge, motivation, and environment are all variables that are interconnected to form creative thinking and problem solving. Seelig illustrates using a continuous ribbon consisting of six parts. The three parts inside are knowledge, imagination, and attitude. The three parts outside are resources, habitat, and culture. This framework reminds me that my students’ creativity is an active state where they are doing instead of waiting to be inspired.

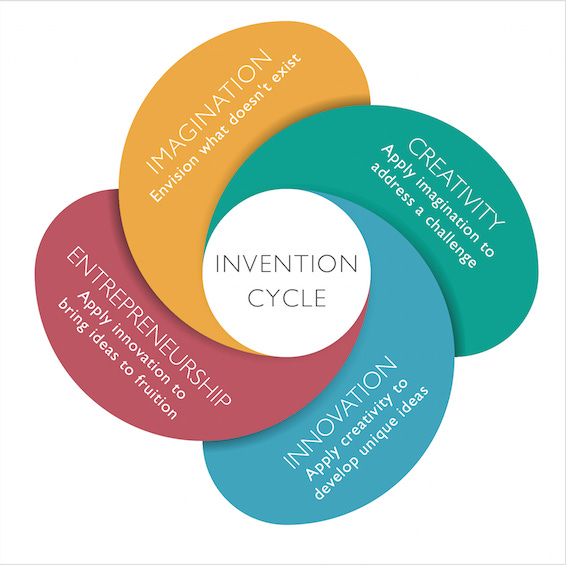

Seelig’s Invention Cycle framework takes her definitions of creativity a step further. She believes that students should not only graduate public education with a strong sense of personal creativity, but they should “emerge from school with agency, feeling empowered to address the opportunities and challenges that await them.” Her Invention Cycle captures the fluid and hierarchical process of moving from idea to entrepreneurship. For example, “imagination leads to creativity; creativity leads to innovation; innovation leads to entrepreneurship.” Each of these elements requires attitudes and actions. Seelig explains this way:

Imagination requires engagement and the ability to envision alternatives. Creativity requires motivation and experimentation to address a challenge. Innovation requires focusing and reframing to generate unique solutions. Entrepreneurship requires persistence and the ability to inspire others.

Students are not only being creative, but are using that creativity to actually create something that will change their world. This framework helps me see how my students’ attitudes and actions are “necessary to foster innovation and to bring breakthrough ideas to the world.” As I scaffold my instruction, I seek opportunities for my students to apply their understanding to a meaningful project. I want them to not only demonstrate their learning, but solve an important problem to them. This way, my classroom becomes an incubator for creativity and innovation.

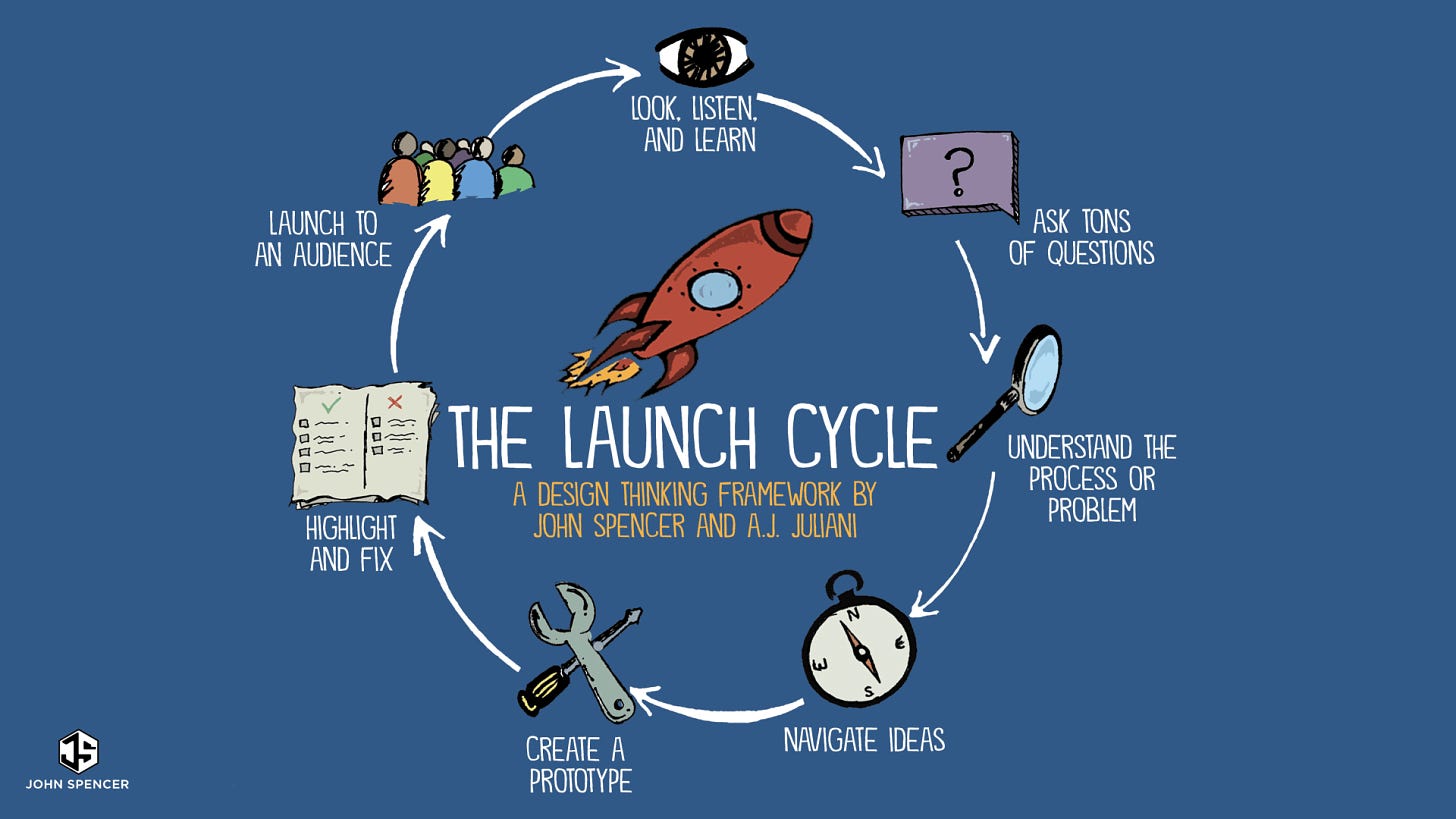

John Spencer’s LAUNCH Cycle is my favorite framework, centered in design thinking. It guides teachers and students to take an idea and see it through to a purposeful final product. LAUNCH is not formulaic or linear. It’s a cyclical process that makes “creativity an authentic experience” in classrooms. This cycle has helped me visualize my learning experiences, planning how I want a lesson to flow.

So what?

In the end, what’s critical is not following a prescribed program or framework, but allowing creativity, and the resulting innovation, to permeate my classroom. Spencer believes that “there is no single creative type.” Couros describes his Innovator’s Mindset as “the belief that the abilities, intelligence, and talents [of students] are developed so that they lead to the creation of new and better ideas.” Seelig understands that “opportunities are abundant; [and] at any place and time you can look around and identify problems that need solving, regardless of the size of the problem, there are usually creative ways to use the resources already at your disposal.”

The above frameworks can and should be used differently by different teachers. Design thinking in my classroom is more than implementing a new technology. Spencer describes it as “more a way of solving problems that encourage positive risk-taking and creativity.” The key to creative collaboration and designing more meaningful learning experiences is to understand that we are all makers, innovators, inventors, and entrepreneurs. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

I learned early in my career, that I need to stop reading the questions from the curriculum and begin creating experiences that inspire engagement. I need to stop inhibiting my students’ natural curiosity and creativity; critical thinking and problem solving; agility and adaptability. It’s my job to help students believe that their voices matter. How they demonstrate their learning matters. It is, in fact, their learning experience. I just create a space for flourishing creativity and innovation.

Each day, I try to look at my 30 students with fresh eyes; looking at my curriculum through the lens of design thinking, and structuring learning experiences so that my students are discovering skills and knowledge and making connections to their lives and other learning; not just memorizing facts. Whether I label any of this as PBL isn’t the point. The point is that my students have an abundance of background knowledge and creative ideas. As their teacher, it is my job to help them use these ideas to learn and grow together.

Have a great week!

—Adrian

Resources

Do yourself a favor and spend an hour getting lost in all of the great John Spencer videos. He makes teacher videos, student design challenges, and learning theory videos; all with excellent, hand-drawn graphics.

Design Thinking - Harvard Business Review

This 2008 article, written by Tim Brown, is still very relevant today.

The Innovator's Mindset Podcast - George Couros

I can’t believe that the Innovator’s Mindset book is almost 10 years old! If you are looking for more current applications, check out Couros’ podcast.

S2, Ep 11. Loni Bergqvist “Wonder & Wander” Podcast

I enjoyed this conversation about transforming schools. Very informative!

The Evolving Role of the Teacher by Dr. Katie Martin

In her book, Learned-Centered Innovation: Spark Curiosity, Ignite Passion and Unleash Genius, Dr. Katie Martin empathizes with the increased demand for teachers to have more creative classrooms. She has pushed my thinking into moving away from student compliance and more toward student empowerment.

McIntosh’s TEDx Talk helped me see the importance of divergent thinking and design thinking in a traditional K-5 learning environment.

I’ve always wanted to take one of Dr. Seelig’s courses at Stanford’s d.school. I’ve read most of her books, including inGenius A Crash Course on Creativity, where she discusses the Invention Cycle.

This High Tech High video goes great with Dr. Katie Martin’s article about the evolving role of teachers.

Bravo

Loved the very fisrt issue I got.