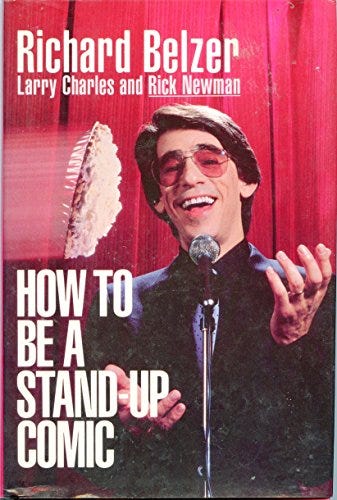

When I was fourteen, I wanted to be a stand-up comic. I remember purchasing Richard Belzer’s book, How to Be a Stand-Up Comic and pouring through it over and over again, looking for the secret steps I needed to take to make it big on stage in front of an audience.

I watched a ton of Comedy Central. I remember spending hours watching my favorite comics: Sinbad, Robin Williams, Margaret Cho, Tim Allen, Paula Poundstone, George Carlin, Eddie Murphy, Dana Carvey, Richard Pryor, Rita Rudner, and so many more.

I’m not sure I learned a lot of technical skills from watching so much early 90’s stand-up comedy. I never became a stand-up comedian. The closest I got was applying to Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Clown College in Sarasota, Florida.

Today, years later, I wonder if maybe I did learn something that I use every day as a classroom teacher.

If you ask any stand-up comedian, they will talk about how much work it takes to become successful. Yes, it’s about solid jokes with tight punchlines, but more importantly, it’s about repeatedly putting yourself in front of a crowd and asking, Do you understand this? Does this make sense? Does this make you laugh?

Today, we are inundated with Netflix comedy specials: perfectly manicured sets, effortlessly executed. The truth is that stand-up comics spend years practicing their routines in comedy clubs across the country. They relentlessly tweak their jokes, sometimes by the placement of a pause or changing a single word, in order maximize laughs. Comics know that you are only as successful as your last joke. Bombing in front of a crowd sounds excruciating, and it is the most successful comics that take that feedback, rework their material, and get back up on stage to try again. Jerry Seinfeld describes his process in phases before he wants to test out his material.

“I have two phases. There is the free-play creative phase. Then there is the polish and construction phase of, and I love to spend inordinate... amounts of time refining and perfecting every single word of it until it has this pleasing flow to my ear. Then it becomes something that I can’t wait to say. And then we go from there to the stage with it. From the stage, the audience will then — I imagine, it’s a very scientific thing to me. It’s like, 'Okay, here’s my experiment,' and you run the experiment. Then the audience just dumps a bunch of data on you, of, 'This is good, this is okay, this is very good, this is terrible.' That goes into my brain from performing it on stage. Then it’s back through the rewrite process and then new ideas will come... [emphasis mine]

In many ways, teaching is very similar to stand-up comedy. You get an idea about how best to present an abstract concept to your students. Like Seinfeld, you take time refining and then you test it in front of your students (a room full of 25 ten-year-olds can be a very tough crowd). If you teach at the intermediate or high school level, you can make tweaks and run the learning experiment multiple times per day.

Seinfeld uses an analogy of archery practice.

“To me is like an archery target, 50 yards away. Then I take out my bow and my arrow and I go, “Let me see if I can hit that. Let me see if I can create something that I could say to a room full of humans in a nightclub, that will make them see what I see in that.”

For me, teaching the fifth grade, I’m gathering data constantly and reworking my lessons on the fly. Sometimes it works and sometimes I bomb. When I completely bomb a lesson, I make major revisions and try again tomorrow.

Bombing in front of a crowd doesn’t feel good, especially after having spent hours planning the activities, embedding technology, and figuring out how you are going to assess learning. Then, there is that gut-wrenching moment when you stare at a room of ten-year-olds and all their eyes are glazed over. Either they have no clue what you are talking about or your lesson doesn’t resonate with them. Unfortunately, some students may just not care. Sometimes getting heckled brings a particular sting.

Heckled from the back

Just like a comic’s heckler, some students seem set on trying to disrupt what is happening at the front of the room. There are a number of reasons why someone goes to a comedy show and begins heckling the comic. Some don’t respect the comedian on stage and see it fit to destroy their set. Some are so engaged with a comedian’s jokes, they can’t help themselves to offer a clever wordplay or repartee.

Jimmy Carr, a British-Irish comedian, is known for his quick comebacks to any audience heckler. In fact, in interviews, he admits that he loves it when someone in the audience participates in the show.

“The idea that when you are in a room with a thousand people who all share your sense of humor. It’s such a waste that they don’t get to say anything. You know that there are great stories out there.” —Jimmy Carr, interview.

I thrive on the energy my students give me during a learning experience. When my students and I are in a interdependent flow state, time dissolves: we are interacting with each other and building each other up. It is dynamic. The classroom is a living, breathing organism that ebbs and flows depending on the bodies, minds, and attitudes in the room. Sometimes, I need to raise the energy levels in the room, especially on Monday mornings. Sometimes, students come in hot, and I need to redirect some of that enthusiasm into our learning experience. When someone has a particularly negative attitude, it can disrupt the classroom’s energy.

Different comedians handle hecklers differently. Some try and ignore them and press on with the show. Some attempt to work in the heckler’s comment to their own joke. I’ve even seen some comedians insult the heckler in order to get them to shut up.

All of these options make sense to me. If you put in hours of work writing jokes; spending hours on stage perfecting your delivery, it can be really upsetting to have an audience member heckle you. Seinfeld has a unique way of dealing with hecklers.

“Very early on in my career, I hit upon this idea of being the Heckle Therapist. So that when people would say something nasty, I would immediately become very sympathetic to them and try to help them with their problem and try to work out what was upsetting them, and try to be very understanding with their anger.”

Early in my career, I don’t remember students being actively disruptive in class. Sure, I remember the quiet, subversive behaviors like asking to go to the bathroom during a particularly challenging part of the lesson, or sharpening their pencil over and over again so that they avoid writing or solving a math problem. However, I never had a student boo me or heckle me in a way that’s analogous to a stand-up comedian.

That’s boof!

Recently, I was delivering some directions for an upcoming learning experience. Disengaged or resistant students are a more common occurrences in my classroom, post-pandemic; however my students this year are a particularly challenging group. Many have had some pretty traumatic educational experiences in previous classrooms. As I was giving these directions, a student named A started shouting, “That’s boof! I’m not doing that. That’s boof!”

This is not the first time that I’ve been heckled by A. He regularly refuses to participate. In fact, he even refuses to play games with the class during breaks in our learning. He responds best one-on-one, but in this particular moment, I was desperately trying to finish my sentences so that I could get the rest of the class working in small groups. So, I pressed on, trying to articulate what students needed to do and what they should be mindful of throughout the process. A wouldn’t relent. “I’m not doing this! This is boof! I’m not working with her.” I wish I could say that I delivered a clever retort that quieted A for long enough to let me finish explaining. No, I ended up telling him that he needed to leave my classroom, step outside for a few minutes.

I hate ejecting students from my room. Especially this year, since I am teaching in a mobile classroom, if I ask a student to step outside, they are literally outside. In the wintertime, this is not an ideal situation.

Once A was outside, I did my best to regain my composure and continue. I fumbled through the rest of the directions, and set the class to work. I joined A outside to figure out what was going on with his attitude. Unlike Seinfeld, I find that most times, being a successful heckler therapist requires one-on-one conversations. Public sparring rarely works on ten-year olds.

We chatted for a bit. Everything I said to try and convince A to return to class and participate wouldn’t work. He kept refusing. He wanted to opt out of the entire learning experience. Nothing I could say or do worked. So, A returned to class and just sat and watched. He was still disruptive, trying to get others off task. I had to ask him multiple times to stop socializing with other students who were engaged.

As I’ve mentioned before, I know that I cannot force real engagement. I can force compliance. I can remove A my classroom. I can redirect A. I can manage his behavior as best as I can, but I cannot force him to opt-in to any learning experience.

A moving target

Whether you are a clown or stand-up comedian or stage performer, you step in front of an audience presuming that they are willing participants in the experience. Theater-goers attend stage performances because they want to see the performance, connect with the actors on stage, and lose themselves in the story. People purchase tickets to watch comics on stage. I know that nightclubs are different than auditoriums, making for a different performer-audience dynamic. People expect to be entertained by a comic and if they are not, there tends to be more parasocial interactions. Many audience members feel obliged to razz a particular comic or add their own jokes, especially after a few alcoholic drinks.

Teachers continue to practice their craft, hitting the moving target of engagement. Not until college, do students pay for their classes. Students under the age of 17 are legally obligated to sit in classrooms. They are not, however, required to learn.

The pandemic gave students across the world the opportunity to opt out of their online learning experiences. Personally, I had students playing Call of Duty while listening to our Zoom lessons. It was virtually impossible [pun intended] to engage students who were blank boxes on my computer screen. I wonder if what I’m describing with A is a residual effect of months of virtual learning. In my school district, we were not allowed to grade any students during that time, only report absences. Students didn’t have to complete any work. Basically, if they logged in every day from March to June, 2020, they passed.

Sometimes, I envy stand-up comedians because they can rework the same jokes repeatedly until they land with most every audience. Middle and high school teachers can teach the same lesson eight periods a day and I’m positive that each one is better than the last. Elementary-school teachers spend seven hours a day, five days per week with their students, many of who really do not want to be at school. I can’t spend months perfecting my lessons for students. In fact, even if I teach the exact same lesson next year, the group of students are completely different with different strengths, weaknesses, personalities, and learning needs.

Lessons from comics and clowns

I’ve been reflecting on my adolescent and teenage dreams of becoming a clown and stand-up comedian. I love making others laugh. I think laughter connects people faster than anything else. People who laugh together are bonded in a shared humanity.

So, how can I recreate this in my classroom? How can I connect even my most disruptive students with their peers? How can I bond with my students?

Here are a few things I’ve learned from comedians that I employ in my classroom.

Be a heckle therapist. Seinfeld is a master at his craft. He understands audiences better than most. I try and channel his skill by being sympathetic to my most disruptive students. When a student is disruptive, there is always a deeper reason. When a student is angry, it can be because they are confused, ashamed, tired, hungry, or all of these combined. My job as a teacher is to try and understand my students and that takes time. Like any parent, I make more mistakes than I want to, but I keep showing up and work to help my students work out what is upsetting them so that they can learn.

No public shaming. As much as I find it hilarious to watch Jimmy Carr roast his hecklers, this just isn’t my personality. Publicly shaming students goes against everything I believe in as a teacher and human being. Yes, a quip can lighten the mood, but never at the expense of a student. Students disengage and disrupt for a variety of reasons and rarely is it because they are out to destroy your lesson. Many times, they are hurting inside and are confused and angry about it. Imagine being ten-years-old and reading at a third-grade level? That causes a lot of lasting hurt that takes time to resolve. Public discipline is ineffective. Public shaming never works.

Levity, levity, levity. As frustrating as disruptive students can be, I’ve learned that almost any tense situation can be diffused with a bit of levity. We all can take things too seriously. This includes teachers. Yes, I want as much student engagement as possible. 100% silence is impossible. 100% compliance does not make for a healthy learning environment. Instead, I strive to create a safe learning environment that allows for making mistakes. Learning to laugh at our own ridiculous or use humor to destress stressful situations is good for our health. This does not mean being self-deprecating. Adaptive (or self-enhancing) humor is a healthy way to cope with stress.

It’s a game of tonnage. Any comic who wants to be successful, spends time writing, practicing, an tweaking their jokes. Seinfeld describes it as getting his work in. He calls it his “work time” saying, “And it’s just work time. It’s just work time. Which, and I like the way athletes talk about, 'I got to get my work in. Did you get your work in?' I like that phrase." Teachers know that masterful teaching takes time. I may not have the ability to practice the same lesson on the same students multiple times, but I do spend 160+ days with my students. I have plenty of time to work to get things right. I put in the work because my students are worth it.

Learning should be joyful. I know that clowns get a bad rap these days. Even before Pennywise, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey was on the decline. After falling attendance and legal disputes with animal rights organizations, Ringling Brothers closed in 2017 after 146 years (they may be making a comeback next year with animal-free circuses and shows touring the U.S.). Why did the circus last almost 150 years? Because it was designed to bring awe and joy to audiences everywhere. Going to the circus as a kid was an experience that is still with me. Why can’t the classroom be the same? I want my students to remember their 5th grade experience for the rest of their lives and I can only do that if I make my classroom a safe a joyful place. Play time should be a formal part of the curriculum. As Dr. Gholdy Muhammad says, “The ultimate goal of curriculum should be joy.”

I’m a teacher, not a stand-up comedian. Perhaps, however, I have a bit of clown still inside of me that works to make my classroom a fun place to learn. I know that I’m not the best teacher in the world. But as Seinfeld explains to young comics, “Learn to accept your mediocrity. No one’s really that great. You know who’s great? The people that just put tremendous amount of hours into it.” I may not be the best out there. My classroom doesn’t have to be perfect. I just want to make it not suck. Every day, I work to make it better. I work to make school not suck anymore, especially for the hecklers in the back.

Have a great week!

—Adrian

Resources

What happens when Jerry Seinfeld decides to heckle a heckler? It’s hilarious!

If you are interested, here is Jerry Seinfeld’s entire interview with Tim Ferriss

The Human Restoration Project is a non-profit dedicated to spreading the word and providing the resources necessary for centering the needs of the human beings at the center of the education process.

Professors at Play invites educators to explore the transformative power of play higher education. Through community, resources and events, Professors at Play looks to challenge existing norms of academia, energize learning and making teaching fun!

As Dr. Brené Brown says, “I am not here to be right, I am here to get it right.”

It's amazing how much better my 6th period lesson is compared to when I teach the "same" lesson 1st period. Getting to make those little tweaks in real time on the same day is one of the joys of teaching high school. It must be hard to teach elementary - you only get one shot! (until next year)