More Than

My plan to get through the next ten years of teaching in the classroom

I’m at the point in my teaching career where many of my colleagues are retiring. I’m not talking about those veteran teachers who are in their 60s and have been teaching for 35 years. After more than two decades in the classroom, I’m beginning to see teachers in their mid 40s leave the profession. Retiring from a service career is never easy and not straightforward. Colleagues may retire because they are worn out from their years in public education; others retire because they want to start a second mid-life career that is less stressful (and pays more) than teaching. I’ve only seen a few teachers make it a full 30 years. Whatever the reason, I find that at 45 years old, I’m looking down the tunnel to retirement and seeing a faint glow from the other side.

Looking back, my first ten years as a teacher, despite being challenging, flew by. I was drowning in No Child Left Behind (NCLB), Common Core Standards, and the introduction of edtech and one-to-one devices in the classroom. It felt like I was using all of my mental resources to tread just below the surface of the water. Often, teachers will use the metaphor of a firehose to illustrate the deluge of mandates and initiatives and curricular expectations that continue piling up each year. The public education system always demands more and provides less, but as a novice teacher, you don’t realize this; you keep a smile on your face and an amicable attitude and keep teaching.

These last ten years of my career are proving even more challenging than my first decade. In 2025, teachers are bombarded with not only the same level of initiatives, but now we are expected to teach during a populist regime, among politicized academic was. Books are being banned while so-called “advocates” are proselytizing the importance of phonics. Wars in reading and mathematics are running in the background to the biggest disruptions to the status quo: The Age of Generative AI.

When ChatGPT was released on November 30, 2022, the internet exploded. Meanwhile, I was still recovering from hosting Thanksgiving and wishing that I had better behaved and more motivated students. Two years prior, during pandemic teaching, I would come home stressed out and write, eventually turning my “pandemic book” into a series of blog posts about the importance of creating learning experiences, instead of delivering lesson plans. I didn’t realize it, but I was approaching a watershed moment in my career; one where I was beginning to realize that all of the struggles I was facing were the product of years of a public education system that treats students like standardized products. I could no longer take for granted that students would just play the game of school. Remote learning gave students a peek behind the curtain and they were not impressed. Two years later, ChatGPT exposed a truth that I was invisibly moving toward despite the myriad distractions and accreting student recalcitrance: teaching and learning require humanity instead of standardization; vulnerability instead of rigidity; empathy over authoritarianism. Learning is more than regurgitating information for meaningless standardized tests.

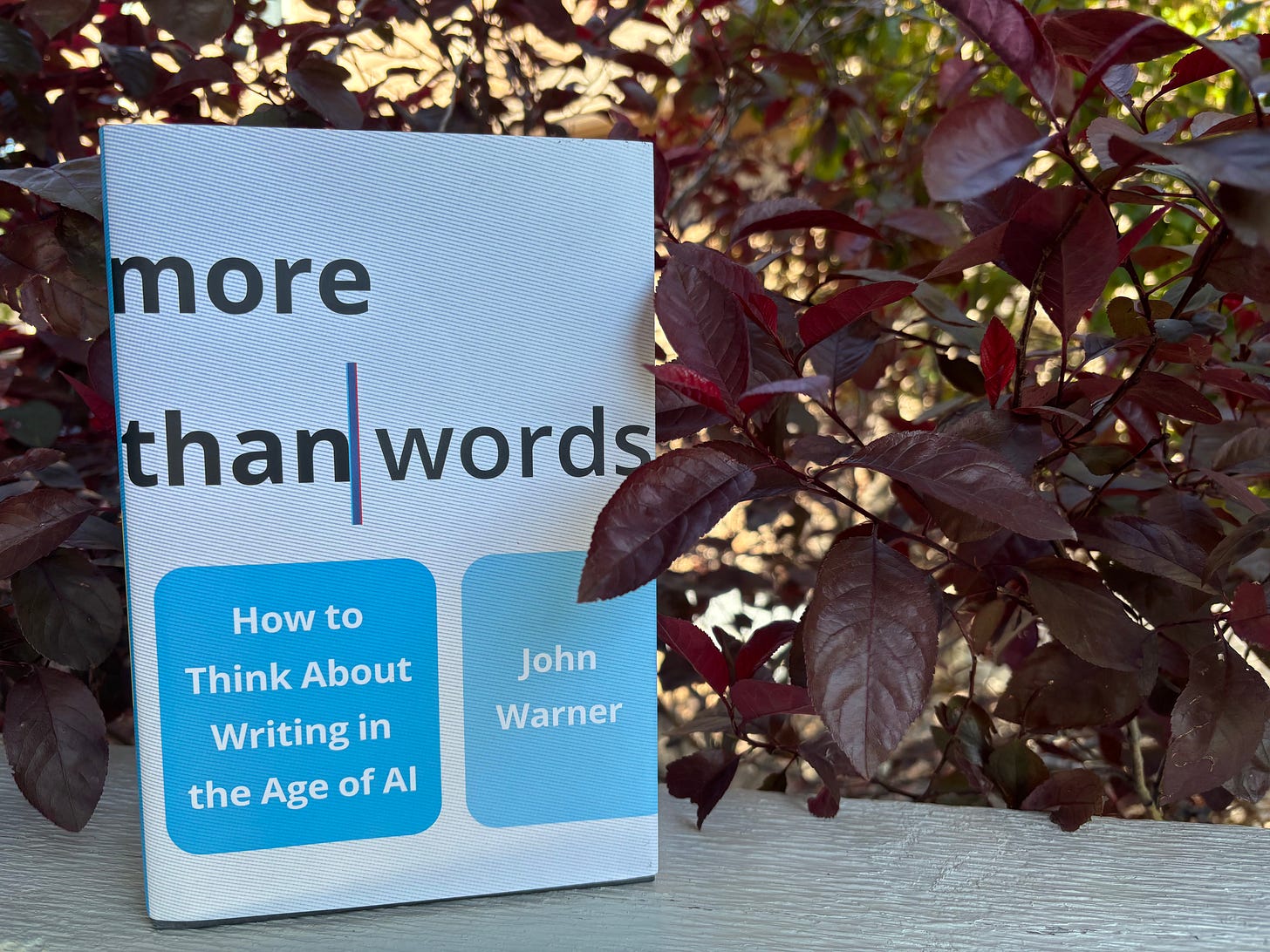

Today, we are still living in the Age of Generative AI. While it is unclear how disruptive ChatGPT (and its iterations) will be, it is clear that large-language models continue to polarize much of society, especially public education. Instead of getting swept up in AI propaganda, in his latest book, John Warner, offers a thoughtfully human approach to generative AI, calmly considering how best to proceed.

Rather than seeing ChatGPT as a threat that will destroy things of value, we should be viewing it as an opportunity to reconsider exactly what we value and why we value those things.

I’ve been a fan of Warner’s thinking about teaching and learning (especially writing), after reading his first book Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities. I had an epiphany midway through the book that the discomfort I’ve always felt when teaching my students to complete their CER paragraphs (in preparation for longer CLEAR paragraphs in middle school and the ultimate five-paragraph essays in high school) is because I haven’t really been teaching my students to write. Instead, I was forcing my students to complete expository faux-writing assignments; the same way I was taught as a student. These dysfunctional structures always bothered me, but as a young teacher, I didn’t have the pedagogical understanding to articulate why. Warner’s teaching experience showed him students were “incentivized not to write but instead to produce writing-related simulations, formulaic responses for the purpose of passing standardized assessments.” Mine too!

I finished Why They Can’t Write and decided to change the way I teach writing. I immediately picked up Warner’s book of writing experiences, The Writer’s Practice: Building Confidence in Your Nonfiction Writing and started adapting his first-year college writing exercises into writing experiences for my fifth-grade students.

At first, I was surprised at how little I actually needed to change. I took the interesting writing problems he gave his college students (e.g., making inferences from observations, writing instructions, analyzing an ethical dilemma) and merely added relevant visuals and videos for my fifth-graders. After two years of using The Writer’s Practice with my fifth-graders, I understand why I didn’t need to change much.

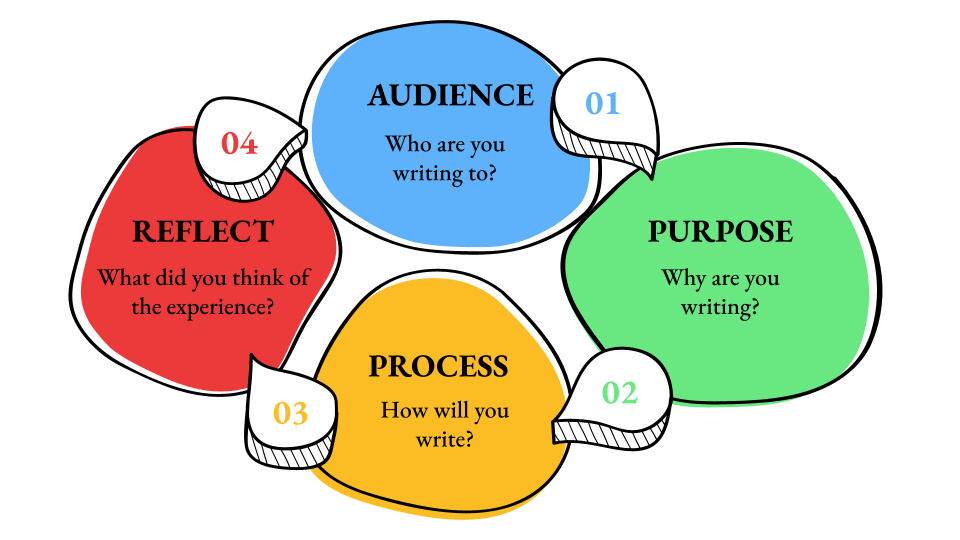

Writing values the process, and the practice-building aspects of these activities, rather than reducing them to limited proficiencies that fit on a standardized test, provides an experience which helps raise student self-knowledge, and self-efficacy when it comes to writing. Once students are engaged and empowered, we can increase the rigor of the work by requiring students to become self-regulating.

It doesn’t matter whether students are ten or twenty years old; authentic writing experiences empower burgeoning writers to tackle rhetorical situations, and even enjoy the process. One of my favorite nonfiction writing experiences is Who Are They? Students observe a pile of personal belongings and generate a list of inferences. They then use their inferences to write a profile of the owner. I love Sherlock Holmes and I use this as an opportunity to share Holmes’ incredible ability to deductively infer from his own observations. I challenge my students to take on the role of a detective, using their deductive reasoning to infer about whose belongings are strewn across my table.

Instead of using the mandated boxed curriculum, having students produce 3-4 writing assignments during the school year, thanks to Warner, my students write a variety of pieces. With each piece, and their process reflections, I see my students learning and improving as writers. In May, looking back on their writing samples from August, the visible growth in each of my students is incredible. Writing is hard, but by giving my students interesting problems to solve, and then letting them write and reflect on the writing process, they are producing better and better writing throughout the year.

Unsurprisingly, I pre-ordered Warner’s latest book, More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI as soon as he announced it. As a fifth-grade teacher, AI hasn’t yet infiltrated my classroom. I know it’s there, though. I may not have to worry about my students using ChatGPT to write their essays (yet), but algorithm-based language models are ubiquitous. Programs like Grammarly use AI to enhance their predictive text and grammar/spell check features. While it is still pretty obvious when my students try to plagiarize something from the internet (copying and pasting paragraphs to avoid taking notes and paraphrasing their research), ten-year-olds in 2025 are living and breathing in a world of automation and algorithmic control. I start each year with a Playlist of my Life narrative writing project. Students learn about me and their classmates through the media we love. I use their song choices to create our Spotify class playlist, collaboratively adding to it throughout the school year.

In recent years, students are less and less connected with music. I first saw this when designing an afterschool vinyl record club, Now Spinning. I was watching my students consume content on TikTok or YouTube instead of listening to full albums. They may be able to tell me their favorite artist (this year, Sabrina Carpenter was popular among my girls), but can rarely tell me the name of the artist’s latest album or another song on that album. My students are living in Filterworld, unable to develop their own likes because they don’t spend more than two minutes with any media online. They are disconnected from their personal tastes, choosing to be influenced by algorithms.

Disconnecting is a trend that I see in other aspects of my classroom, too. It is a problem I first noticed last year with my students’ increasing disengagement. Their attentional presence is quickly atrophying, and more students are struggling to see the purpose of schooling. Warner sees this is as a sign of “a bad disconnect between schooling and learning.” School has become a depersonalized banality filled with meaningless academic transactions promising to “prepare students for the real world.”

I wanted to read More Than Words because knowing Warner’s stance on writing as a process for thinking, I suspected he had much to say about writing in this AI Age. Large-language models are accelerating exponentially, so I best understand them.

I intentionally saved More Than Words for my first summer read where I could give it my full focus. As Warner states, “writing should be read” and since he has been so influential in improving my own pedagogical writing practice, I wanted to take my time to fully process what he has to say about our relationship with writing.

I was not disappointed.

In some ways, More Than Words, is even more affirming of my pedagogical beliefs than his first two books. In reading Why They Can’t Write and The Writer’s Practice, Warner introduced me to the systemic problems associated with formulaic responses for higher test scores. In reading More Than Words, he not only gives readers a useful framework to think about generative AI, he is helping to sustain my spirit by giving me a map for rethinking my relationship to teaching during these next ten years.

For 20 years, I have been doing my best to navigate a public education system fraught with problems. I’ve always had overcrowded and underfunded classrooms. Every time I feel like I am making progress at changing the status quo, another curricular initiative is introduced pushing me five steps back. I’ve been teaching long enough to see multiple pendulum swings. I’ve been a teacher through both the reading and math wars, swinging from phonics-based to whole-child instruction. I’ve been coached to be standardized and data-driven, and then student-centered. I’ve been encouraged to use gamified technology to enhance student learning, and then found myself reintroducing my students to pencils and paper and the human complexities inherent in education. Now, large-language models threaten to make me obsolete. More than anything else, More Than Words eases my anxiety about being replaced by machines. Warner reminds me that teaching and learning are uniquely human skills, and that will never change. I’ve known this for many years, but sometimes it takes a gentle shake on the shoulder. I am grateful for Warner’s meditation on AI. He may focus on writing, but his steady examination of AI reassures and affirms my belief that the best way to grow students is to lean into their humanity. Writing is more than generating syntax. Writing is thinking and feeling and a lifelong practice. Teaching and learning and reading and writing are all innately human acts and to outsource them to AI, albeit attractive, diminishes our collective humanity. This is how I plan to continue teaching another 10+ years: focusing on our collective interdependence and creating algorithm-free learning experiences that strengthen our classroom community.

Resist, Renew, Explore

John Warner’s framework for thinking about generative AI supplements my pedagogy. This isn’t a fad promising to make teaching and learning with AI easier. It isn’t something that will go stale as large-language models continue to grow. Warner gives us a “way of thinking about this technology in the context of a goal of giving humans the space to live good lives.” I’m more concerned with my students flourishing as humans, than increasing their test scores, so resisting, renewing, and exploring give me hope that my last decade in public education will be meaningful and enjoyable.

I have some experience resisting the status quo. Especially post-pandemic, I have worked to shift my pedagogical practice to one that his more humane and humble. So, I’m confident that I will be able to resist the inevitability of AI taking over my classroom. When Warner discusses the concept of an economic style of reasoning, I nod my head and think about all the ways I push against the speed and efficiency expected of me as a teacher. Instead of forging through curricula, I try slowing down. Instead of accelerating the pace of standardized lessons, I teach with meaningful deliberation.

Warner reminds me that I’m not a teaching machine. My students are always more important than the system. And even when I see that my test scores are not as high as others, I remember that often, the teachers with the highest test scores tend to be the ones who are the least compassionate with their students. Striving for higher and higher standardized test scores dehumanizes everyone involved. It amplifies the zero-sum game of public education and diminishes the humanity necessary to build an embodied classroom community. I choose to teach spiky humans, not averaged data, and to do so effectively, I continually revise my approach in service to my students.

We live our lives through a series of experiences rooted in a community of fellow humans.

John Warner, More Than Words

Where I need to focus my efforts now is in finding guides for navigating the Age of AI. I appreciate Warner pushing me to explore different perspectives. I have some experience with seeking different opinions to my own, specifically with race, equity, and social justice. However, researching and thinking about AI often lead me into all-or-nothing echo chambers. I’m grateful that Warner shares his guides, including Dr. Sasha Luccioni, Dr. Alex Hanna, Dr. Timnit Gebru and Dr. Margaret Mitchell. My goal in this upcoming school year is to find more guides that will help me negotiate what ChatGPT and generative AI look like in an elementary-aged classroom. My students are nascent writers and I’m tempted to outlaw any attempt to offload their thinking to machines. I want to help my students become writers, not form-fillers. I can hold this value while widening my circle to include opinions contrary to my own.

I’m not surprised that I gained so much from reading More Than Words. I am familiar with Warner’s ideas about teaching writing. I know how he feels about writing as thinking, and I wholeheartedly agree with creating meaningful, authentic writing experiences for my students instead of transactional templates to complete.

This book is more than just pedagogical affirmation. It is more than a reminder to be human in my classroom with my students. Reading More Than Words gives me hope for my later years as a teacher. I don’t have to, nor should I, resign myself to the dehumanizing pace of school or the inevitability of generative AI. Just as writing is more than syntax, more than putting words in boxes, teaching is more than any standardized curricula. School is more than a series of transactional chores. Learning is more than demonstrating proficiency. If I’m going to make it another 10+ years in the classroom, I should give myself the best possible chance to teach and live in ways that honor and amplify my humanity and that of my students. We need more books like this. More Than Words is an excellent rumination; one I will be revisiting often.

Have a great week!

— Adrian

Resources

Many people have written thoughtful reviews of More Than Words and insightful pieces on ChatGPT and large-language models. I highly recommend you read (or listen to) a few of these alongside John Warner’s latest book.

Marcus Luther does an excellent job reviewing More Than Words. In fact, he even got a chance to chat with Warner for his podcast, The Broken Copier. You can view his entire conversation here.

If you want a taste of Warner’s thoughts about generative AI and outsourcing students’ thinking to ChatGPT, read his post on The Biblioracle Recommends.

Emily Pitts Donahoe also interviewed Warner. Donahoe’s Unmaking the Grade ungrading newsletter is a wonderful lens through which to read More Than Words.

Another great thinker and writer on generative AI and its impacting education is

Marc Watkins. His Substack, Rhetorica, is filled with essays on AI’s effect on our ability to read, write, think, and communicate.

Warner references Ethan Mollick’s book Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI as a counterargument to generative AI. Warner encourages us to explore different perspectives instead of living in our self-created echo chambers. If you are looking for a counter-narrative to the doomsayer conversations about ChatGPT, I highly recommend Mollick’s newsletter, One Useful Thing.

This video shows what it might look like for elementary-aged students to use AI chatbots in the classroom. This STEM teacher is working with students to improve their digital literacy and critical thinking skills.

MagicSchool | AI for Educators

MagicSchool has come up in a few conversations with colleagues. I’ve seen teachers use AI to generate texts for students to assess specific reading skills (e.g., inferencing, finding main idea, etc.). I’ve experimented with ChatGPT and MagicSchool to write plans for a substitute teacher. I find results lackluster, but I worry that soon, teachers will be using AI platforms like MagicSchool to plan lessons, instead of designing learning experiences tailored to their students.

Shortly after ChatGPT was released, I signed up to be a beta tester for GPTZero. Like many teachers, I was afraid that I would receive a deluge of AI-generated writing from my students, and would need a way to detect human from computer. Thanks to using John Warner’s writing experiences with my students, they aren’t using AI to do their writing. Edward Tian and his team now offer a GPTZero certificate program and webinar: Teaching Responsibility with AI.

I always love listening to students discuss their personal experiences with public education. Orisa Thanajaro is a 16 year old Thai student whose traveling experience sparked her interest in education. She seeks to one day revolutionize the Thai education system to become more impactful and useful for Thai students.

Recently, Joseph Gordon-Levitt spoke with Ina Fried, the tech correspondent for Axios, about AI and the entertainment industry. I’ve enjoyed his Joe's Journal Substack, and his reflections on a variety of topics. While this interview isn’t directly related to AI in education, Levitt’s is excited about the potential for AI in creative fields. While I believe that creators should be compensated, I’m not sure if I share his enthusiasm for using AI to enhance creativity. Still, Levitt’s perspective is one that I’m considering as I help my students navigate AI.

I respect your perseverance, Adrian, and to be honest, I have hope for our kids' futures because of educators like you. We appreciate you sharing your in-depth thoughts on the pursuit of constant improvement. https://grow-agarden.io

Thanks for this. I heard Warner interviewed on a podcast and wondered if I should get the book. You have convinced me!