AI and education seem to be what everyone is talking about. Depending on what you read, these are either extremely exciting or terrifying times for public education. On one hand, AI will revolutionize how students learn. On the other, students will use AI to either cheat on tests or use it to do all types of writing, from email to college essays, while teachers will use it to monitor and manipulate students.

I’ve avoided entering the fray, mainly because I don’t see AI infiltrating my fifth-grade classroom any time soon, and, more importantly, there are others who are more knowledgeable and write more eloquently on the subject.

has been writing sharp essays intelligently critiquing the use of AI, specifically in writing, for over a year. He contributes regularly to Inside Higher Ed, has his own master course on teaching writing in an AI world, and has an upcoming book titled, More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI. My favorites of his are Writing is Thinking and ChatGPT Can't Kill Anything Worth Preserving. Warner has influenced how I think about my own writing and how I teach my students to be better writers and thinkers. This year, I’ve been using his book, The Writer’s Practice in my classroom, giving students authentic rhetorical experiences instead of forcing them to “produc[e] writing-related simulations, utilizing prescriptive rules and templates (like the five-paragraph essay format), which pass muster on standardized tests, but [do] not prepare them for the demands of writing in college contexts.” It has been a great experience. My students are writing more and better drafts than I’ve ever seen before.Marc Watkins is also a teacher and writer with a vested interested in AI and education. His Substack,

, is full of thorough essays on generative AI and its impact on teaching and learning. He also writes guest posts for Inside Higher Ed.Needless to say, if you want well-researched and astute writing (as well as tons of resources) regarding AI, I highly recommend you read both of their Substacks.

Recently Watkins wrote a piece titled The Enduring Role of Writing in an AI Era. In it, he discusses our history of offloading the labor of writing to algorithms.

Watkins thinks about AI through a higher education lens. However, I was struck by the idea of offloading labor to AI, and how it relates to my teaching career. I think there has long been a fascination with offloading the work of teaching to technology. I remember the rise of the 21st Century Learner, Wikipedia, and MOOCs. Whether it was Web 1.0 and 2.0 tools, flipped classrooms, gamified apps, or ChatGTP, there always seems to be a prevailing notion that technology gives students more of what they need (and does a better job) than teachers. As a teacher, how can I compete with machine learning? A gamified computer program can help my students master a particular concept more efficiently than I can with a classroom of 30 students, all with different learning gaps, needs, and strengths. Right? There is an allure to the idea that I can plug students into the computer and after 15 minutes they re-emerge with better conceptual understanding. It seems like the ultimate shortcut or hack to learning.

Over the last 20 years, I believe that we have become obsessed with finding shortcuts. Why listen to an entire album when I can skip ahead to my favorite song? Why read an entire book before class when I can use CliffsNotes and SparkNotes? I can use Blinkist and Four Minute Books instead of sitting down to read a novel or Shortform to summarize nonfiction. I can even reduce my knowledge into bite-sized lessons.

What people don’t realize is that while machine learning may be more adaptive, authentic teaching and learning will always be a human experience requiring human to human interaction. I may be able to learn something from a computer, but I won’t remember it nearly as well as a conversation I had with another person. I won’t be able to make connections to other aspects of my life. Learning is vulnerable and an innately social act, and AI will always fail in replicating the social humanness of learning. Augustine of Hippo says that “our ability to love one another depends on our capacity to learn from one another” and we cannot learn from one another if we are all plugged into our devices.

There are no shortcuts to deep and meaningful learning. I want my students to have an intellectual life, not just a series of regurgitated, bite-sized opinions. Deep thinking takes time and effort, something I’ve been experimenting with in my classroom lately. I’m striving toward an ethos of communal intellectualism. I’m trying to push my students toward the common goal of promoting a shared intellectual life, not just passing a test. I want my students to delight in learning and understand complex topics in a way that enhances their lives, not just increases their test scores. This takes time; more time than what is allowed in the standardized system of public education. When we try to bypass the time and effort involved in teaching and learning, we reduce ourselves to shallow soundbites and AI-produced blurbs or ChatGTP essays. Ancient philosophers were “lovers of wisdom”; not algorithms.

Empathy and Journey Mapping

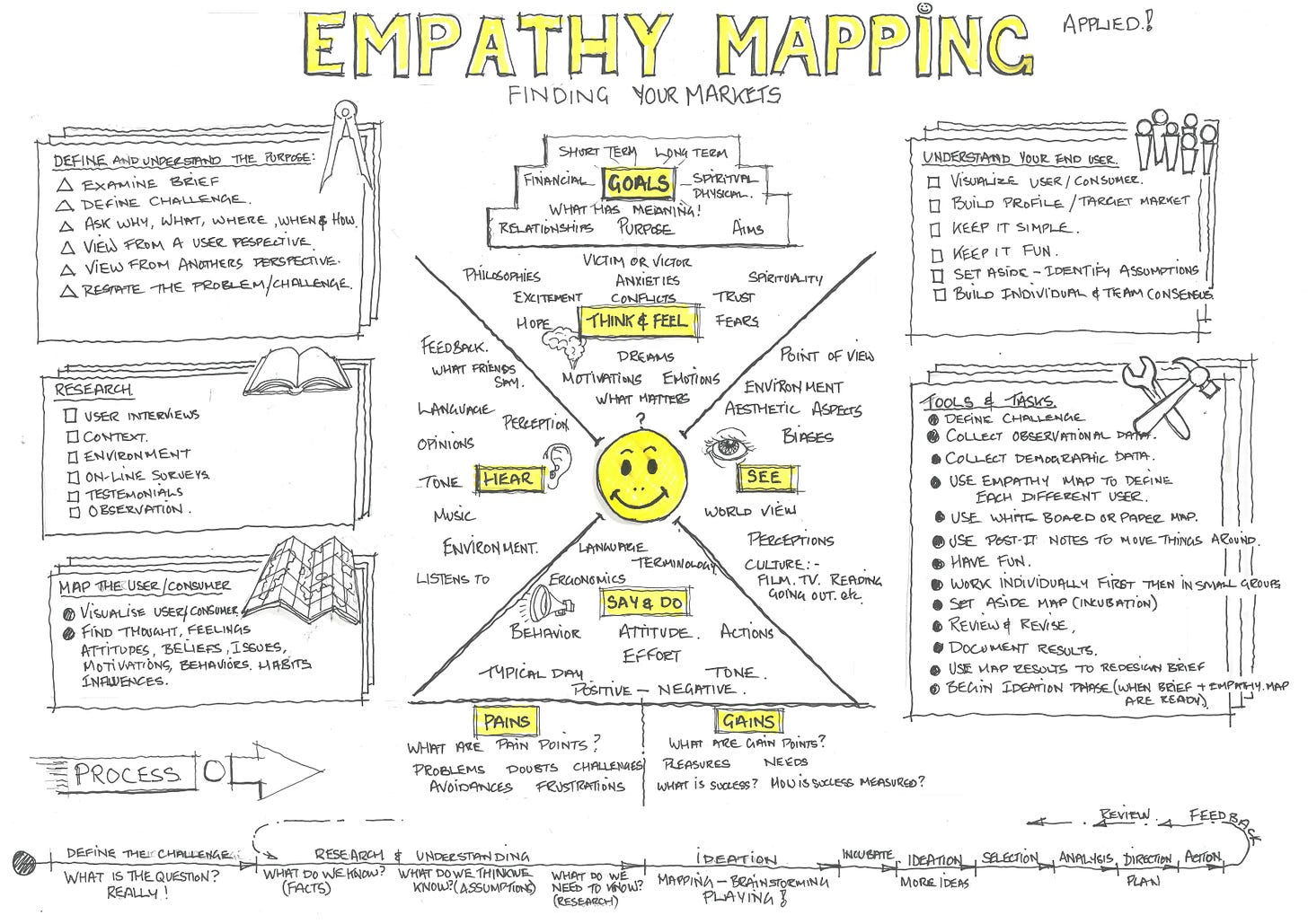

One way I resist the urge to automate my teaching, or speed up my students’ learning, is through empathy maps and journey mapping. A journey map helps me gain important information in how my students will experience an upcoming learning experience by better understanding their learning processes. It is most often used in customer or user experience design. For example, design firms will map the steps a customer will take in ordering a cup of coffee or purchasing something online. They then identify the positives and negatives in order to improve that experience. I storyboard learning experiences in order to identify touchpoints, areas where students interact with a particular concept or question. I then structure a sequence of activities that build upon one another, leading students to a more authentic learning experience.

Even though empathy maps are primarily used after an experience, I use empathy mapping when trying to identify the thoughts and feelings of my students before, during, and after a new learning experience. Before I test out new experiences, I informally interview a few of my students to elicit their perspectives (e.g.: students who absolutely love school and students who have negative experiences with school). This helps me uncover new insights, and plan for how I might meet their needs during the learning experience. Once I have some of my students’ perspectives, I use an empathy map to help me record and start synthesizing their comments. I want to draw out unexpected insights that may come up during the learning experience.

I use what my students SAY during the interview and the try to imagine what they may THINK and FEEL during the learning experience.

SAY: What are some student quotes and defining words?

THINK: What might students be thinking? What does this tell you about their beliefs?

FEEL: What emotions might students be feeling?

For the DO quadrant, I plan the learning experience from start to finish using IDEO’s AEIOU Guide:

ACTIVITIES What are students doing and why might they be doing it?

ENVIRONMENTS What does the classroom look like, and what’s in it? How will the classroom either hinder or help the learning experience?

INTERACTIONS How are students interacting with others in this space?

OBJECTS What physical objects are in the space and how are students using them?

UNDERSTANDING Based on what I’ve observed, what new insights or understanding have I gained? Were any ideas sparked?

Once I test this experience with my students, I return to the AEIOU prompts and use them as an observation guide, adding new insights and ideas. This helps me fill in the DO quadrant with my students’ behaviors and actions. I can also infer my students beliefs and emotions, adding these to the empathy map in the THINK and FEEL quadrants. Empathy maps are also great reflection tools to use with students in evaluating the learning success of a particular experience. It makes for a great classroom discussion.

Wouldn’t it be easier to select a learning standard from a drop-down list, assign it to my students, and then let them log in and complete a gamified activity, which uses AI to cater to my students’ individual learning needs? Perhaps, but this is not teaching and learning. This conflates machine learning with student learning. Students are not machines. Meaningful teaching and learning are messy and are human-centered.

Teachers who have a deep understanding of their students know their academic strengths and weaknesses. They take time to form strong relationships with their students, understanding their cultural identity and the asset-focused factors that will help students be successful. They know that the process of teaching and learning is active.

A rigorous learning experiences offers students more than fancy edtech or AI tools. Teachers who build students’ content knowledge while simultaneously acknowledging and validating their everyday experiences and interests, help students grow beyond improving a test score. Teaching in a classroom with 30 students is dynamic and alive; there is interpersonal give and take, almost like breathing. Teachers make learning feel alive. Their classrooms are filled with love, authenticity, and intentionality. Dr. Adeyemi Stembridge explains that masterful teachers “choreograph rigorous and engaging learning experiences that draw richly on students’ strengths and identities by building upon their assets.” These classrooms invite students to bring their whole selves to school every day. Dr. Christopher Emdin describes this as ratchetdemic, allowing students to be both their ratchet and academic selves. Teachers who teach the kids in the room, not the scores in the gradebook, empower students to embrace themselves, their background, and their education.

Authentic and dynamic learning experiences seems effortless, but require empathy and intentional planning. It takes time to build mutual trust with my students and use this trust to build a loving teacher-student relationship that empowers them to learn beyond my classroom. I may not be able to compete with AI’s efficient machine learning, but I don’t want to. I’d rather invest in teaching to my students’ humanity, creating classroom experiences that will help them grow as human beings. I’m not looking for AI-powered shortcuts in my classroom. I’m not worried about being replaced by Pepper, the humanoid robot. There are no shortcuts in the type of learning I’m interested in for my students. I don’t believe that teaching my students how to learn and how to be better people in the world will ever be killed by AI. Or as

states, “ChatGPT can't kill anything worth preserving.”Have a great week!

—Adrian

Resources

Build Your Creative Confidence: Empathy Maps - IDEO

I first learned about Empathy Maps from David Kelley’s book Creative Confidence. It is a great book that has helped me empower students and teach them how to develop a more creative confidence in their work.

I learned about Aspen Labs when I was the STEM and Innovation Coordinator for our K-5 Elementary Schools. The above link has excellent resources for human-centered design thinking that you can use in your classroom.

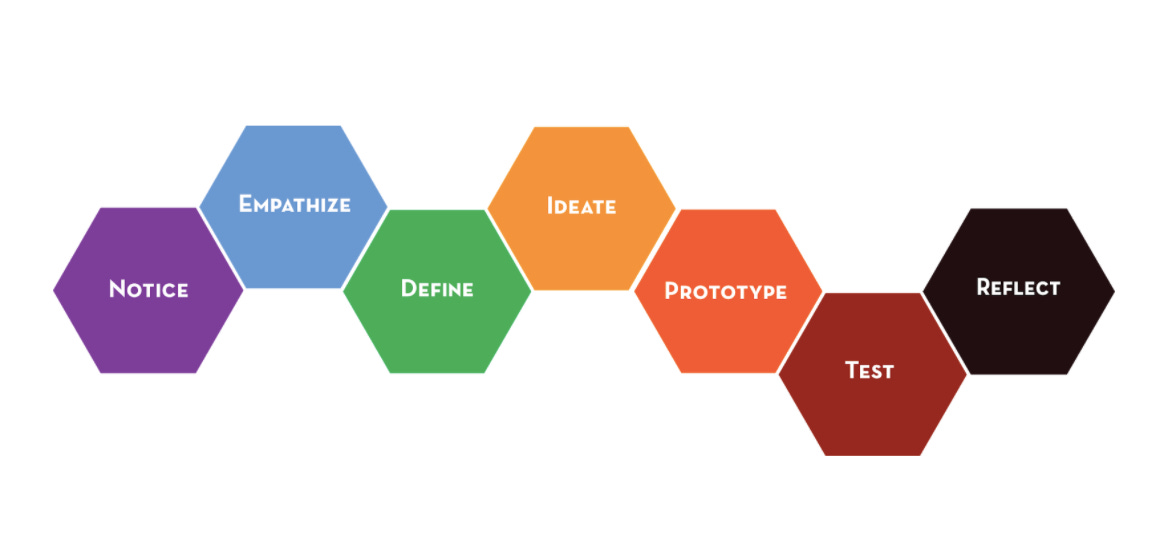

Equity-Centered Design Framework - d.school

I’ve been using d.schools’ Design Framework for a number of years. In 2016, they updated it in order to incorporate self-awareness as a equity-centered designer.

Design Thinking Bootcamp Bootleg - d.school

This toolkit is a great resource for using design thinking. I’ve used many of these activities with my students.

The Co-Designing Schools Toolkit is a collaboration between The Teachers Guild x School Retool. I was lucky enough to participate in virtual It Starts With Schools experience, where I first learned about this toolkit. They published a Learning Reimagined report that continues to guide my pedagogy.