What if?

Chapter 4: Dreaming a vision for schools

Happy Sunday!

Here is my summary, reflection, and discussion questions of Alex Shevrin Venet’s Becoming and Everyday Changemaker: Healing and Justice at School. If you’ve missed any of our previous posts, I’ve linked them below. Leave a comment and keep the conversation going!

Chapter 1: Messy Scares Me (And That Might Be a Problem as a Teacher)

Chapter 2: I'm exhausted!

Chapter 3: When SMART Goals Aren't That Smart

In each post, either Marcus or I will provide a brief summary of the week’s chapter, a reflection, and a series of discussion questions designed to spark a conversation in the comments. Feel free to jump in at any point! You can also find our entire fall reading schedule and vision (with links to each chapter’s post, reflection, and discussion) here.

In Chapter 4: Dreaming a vision for schools, Venet asks us a simple question.

When you dream of school, what do you see?

In the previous chapter, Venet critiques SMART goals and public education’s obsession with quantitative data. By focusing on concrete and measurable metrics, we fail to create visions for change. “To create a vision” Venet states, “we need to dream.”

Dreaming isn’t merely imagining. Dreaming is an act of resistance to the status quo.

We have to push ourselves to think beyond what can’t happen and to think instead of our duty as holders of dreams. We must move through this moment by radically dreaming and hearing the dreams of others.

Jamila Dugan

Venet gives us space to dream in this chapter. She invites us to let the what-abouts go and dream of the what-ifs. “Change can be fueled when we radically dream” and this chapter is filled with dreaming prompts that help us create a vision for the “future we want for ourselves, our students, and our communities.” In finding a path toward change, Venet discusses how we can use these visions to inform the change process.

I’ve been thinking about what-ifs for most of my teaching career. I wasn’t an exceptionally inquisitive child; I probably annoyed my parents with the standard number of questions kids ask. What really annoyed me was the stock answer my father always gave whenever I asked why.

Because I said so.

As a parent of three teenagers, I have more empathy for my father’s exasperation. I can see why he wouldn’t entertain possibilities. It’s easy to get stuck in the status quo. in my weariness, I’ve been known to throw out that response at my kids a few times.

As a teacher, I’ve never been satisfied with the obstacles (real or imagined) that dictate much of our teaching practices. In my first years of teaching, I asked a lot of questions.

Why aren’t we allowed to have a morning and afternoon recess?

Why do I have to arrange my desks in rows?

Why do I have to follow this curriculum? Why can’t I supplement with other resources?

Why don’t we read outside today?

Why can’t students create a presentation instead of writing a report?

Why can’t I have a Makerspace in my classroom?

Why can’t I nominate more than one Student of the Month?

Why can’t my after-school club be only for boys of color?

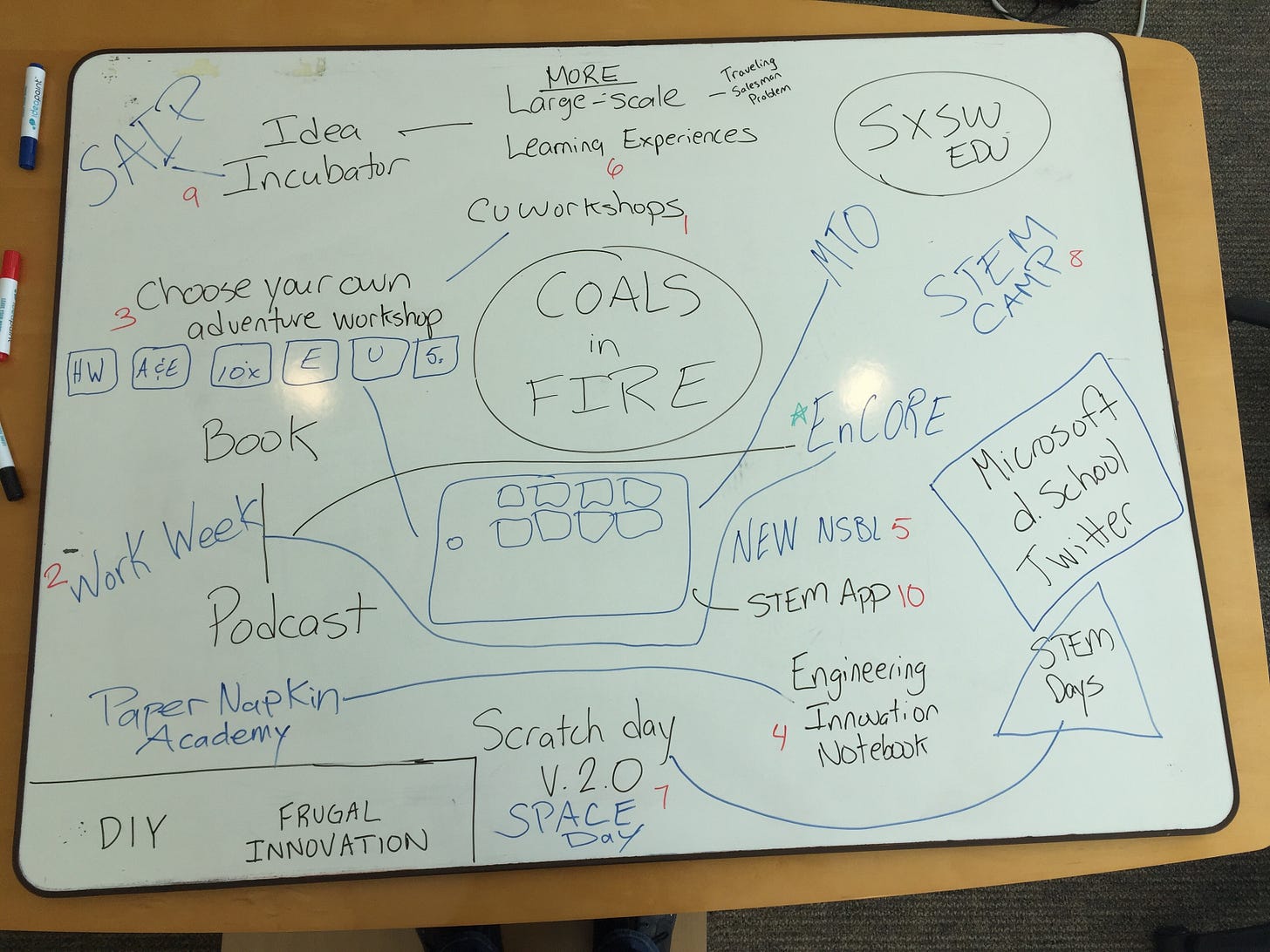

My pedagogy of why-nots tested my colleagues’ patience. More often than not, the answers sounded a lot like my father’s response: because that’s the way we’ve always done things or the more annoying that’s NOT the way we do things here. As Venet states, these cloud our ability to imagine teaching and learning beyond them. It wasn’t until I left the classroom to be a STEM and Innovation Instructional Coach, that I was given permission to dream bigger than my classroom or school building. For every project we imagined, we worked to scale it to all of our 44 elementary schools. STEM for all!

We wanted to design large-scale learning experiences that reimagined what school could be. I learned from people like Astro Teller, Dr. Tina Seelig, and Peter Diamandis, and from institutions such as IDEO, Stanford’s d.school and Harvard Innovation Labs. I began using terms like moonshot thinking, 10x, disruption, radical collaboration, and design thinking. The funny thing about dreaming is that once you start, it is hard to quit. You start questioning everything! “Imagination gives us agency” (p. 76) and having agency is a powerful thing; you don’t want to give it up.

During those six years, I tried waving a magic wand to create a different type of public education system. I dreamed of a school where students are so excited about what they are learning, that they can’t sleep at night in anticipation of the next day. I dreamed of an system that allowed teachers to design learning experiences instead of delivering standardized lesson. In my visions, the process was innovative and flexible. The main duty of teachers and administration was to radically improve public education by engineering a culture of innovation and exponential growth.

Now that I’m back in the classroom, I’ve brought my dreams with me. The visions I continue to dream ask big questions that other people don’t ask, challenge the status-quo, and keep asking why something can’t be done. The best part of having these moonshot ideas is not in the fulfillment of the idea, but in the process of working toward something challenging, and innovating against the tide of conformity.

Now it’s your turn!

Jump into the comments and share your thoughts, questions, or anything you’d like about Chapter 4. Remember, the above discussion questions are just a guide. Feel free to share how this chapter resonates with you and your own experiences.

Next week, we begin reading Part II: Equity -centered trauma-informed skills for navigating the change journey. Marcus Luther from The Broken Copier will share his thoughts on one of my favorite topics, Chapter 5: Both/and. See you then!

Dreaming big and implementing these ideas into a mainstream classroom is so important! Not enough teachers dare to do this and I can understand why. Thank you for all you do for your pupils, Adrian 😊

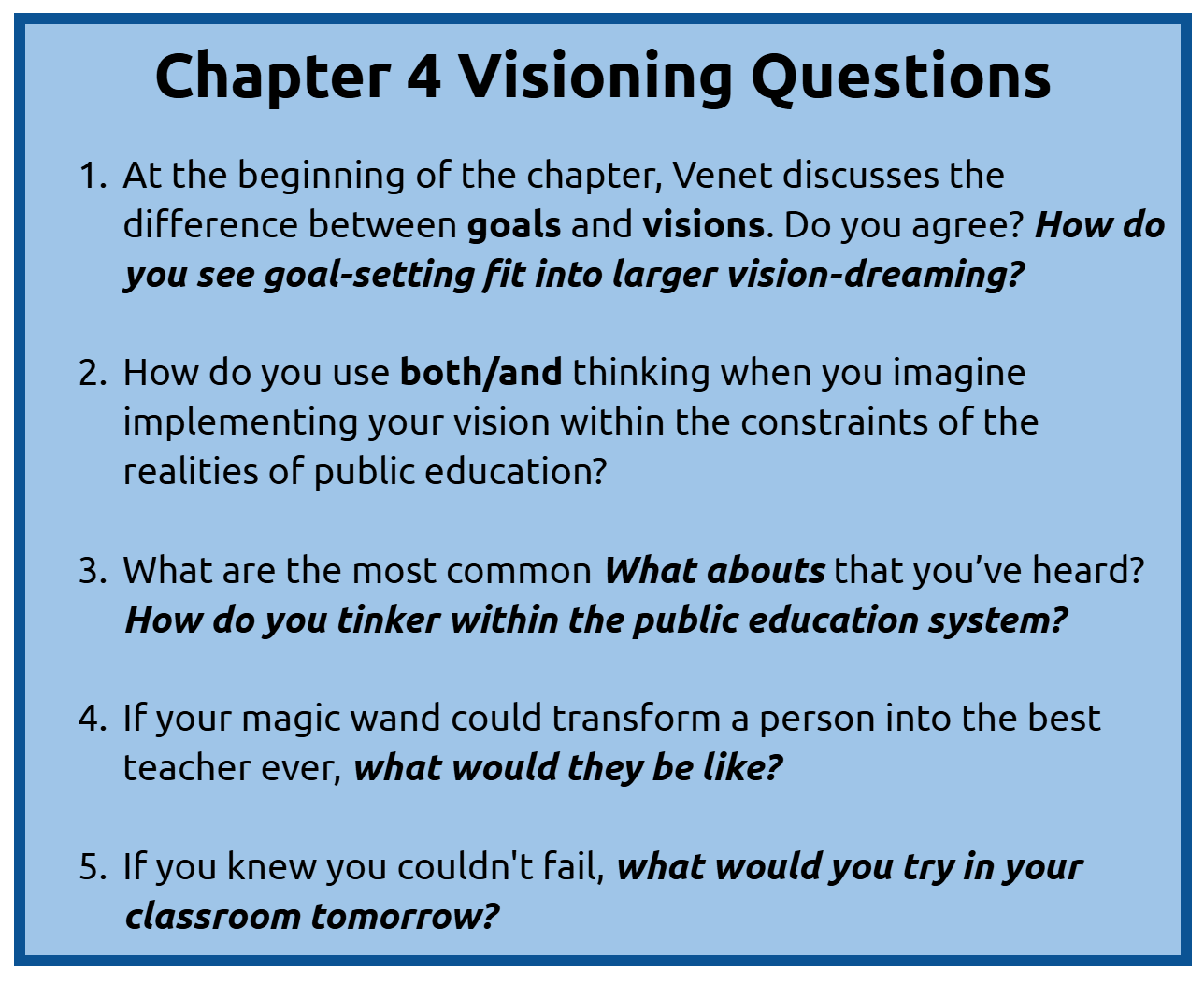

For me, the most resonant and affirming point in this chapter is the idea that we cannot be driven by goals nearly as much as our vision for what we want our classroom and schools to be.

In early years of teaching, I would easily get discouraged by specific goals not being met because I had centered them as the be-all and end-all of our classroom—but shifting to a focus on the umbrella that is the vision of our classroom, with goals living underneath it, has given me a more resilient way to be hopeful for where we are heading. (And also to be flexible to what the classroom needs to be for students, too.)

There are many things about this chapter that have me wondering/dreaming, but that intentional shift of moving from centering goals to a vision? Just imagine what education would look like if we could all move that direction...