Decentering Whiteness in my Classroom

Exploring my classroom cultural values and habits

I work hard to create a classroom that sits apart from the standardized status quo of public education. My classroom is a place where my students can be their whole selves; a learning environment where they can recuperate from the traumas and microaggressions of previous classroom experiences. My classroom is seen as irritating to some teachers and inviting to all students. I often get noise complaints from teachers who are desperately trying to convince their students that sitting quietly in rows is better than what is going on in Mr. Neibauer’s room.

Aside from the more obvious reactions to my classroom, over time I’ve observed two things. First, every year, I receive the most challenging students. These tricky treasures always accompany my new roster with similar comments: This student could really use a strong, male role-model or I think this student will do well in your class with the way you run your classroom. They are overwhelmingly boys of color, all being shoved in my classroom because no one else wants to have them in their classrooms. Secondly, if I stay in a school building long enough, I am moved to a mobile classroom where my students and my teaching will be less disruptive to the rest of the building.

I’ve become accustomed to these phenomena. I know why they happen and I’m certain they will continue as long as I am teaching. My pedagogical practice looks quite different now than it did twenty years ago. When I was a student, my teachers had authoritarian pedagogical styles. This does not work for my students. They demand more from me than traditional teachers. I may not teach in an urban school district, however, I have had to flip my pedagogical practice from dehumanized, teacher-centered teaching to what Dr. Christopher Emdin calls reality pedagogy.

Reality pedagogy is teaching and learning based on the reality of the students experience.

Dr. Christopher Emdin

When I first started teaching, I suffered from white saviorism: I believed I knew what my students needed and I tried to give it to them within the constraints of a standardized public education system. The more I learned from my students, and the more comfortable I got with subverting the system, the more I realized that I couldn’t sugarcoat standardization. I couldn’t justify dehumanizing school policies like shaming students as a form of discipline and refusing to empathize with students. I couldn’t micromanage my students; not only does it go against my values, but it is virtually impossible to control 30 students without resorting to totalitarian methods. So, I began to create a classroom where my students are allowed to feel human. Rehumanizing teaching and learning and decentering my whiteness have been the most important decisions I’ve made in my teaching career. Here are a few examples of how I continue to examine and decenter my whiteness in service to my students.

Individualism versus Collectivism

Dominant white culture values a separateness in work, favoring the individual efforts of one person over the collective efforts of a group. So, too in many classrooms, students are required to work independently and recognition is often given to a single student, even if peers are involved. Although this is the way I was taught, these habits have never worked for me. A classroom culture of separateness is not conducive to my values of collective growth. I believe in collectively creating a positive classroom community. One way we do this is by following these Guiding Principles from Michael Sorrell, President of Paul Quinn College.

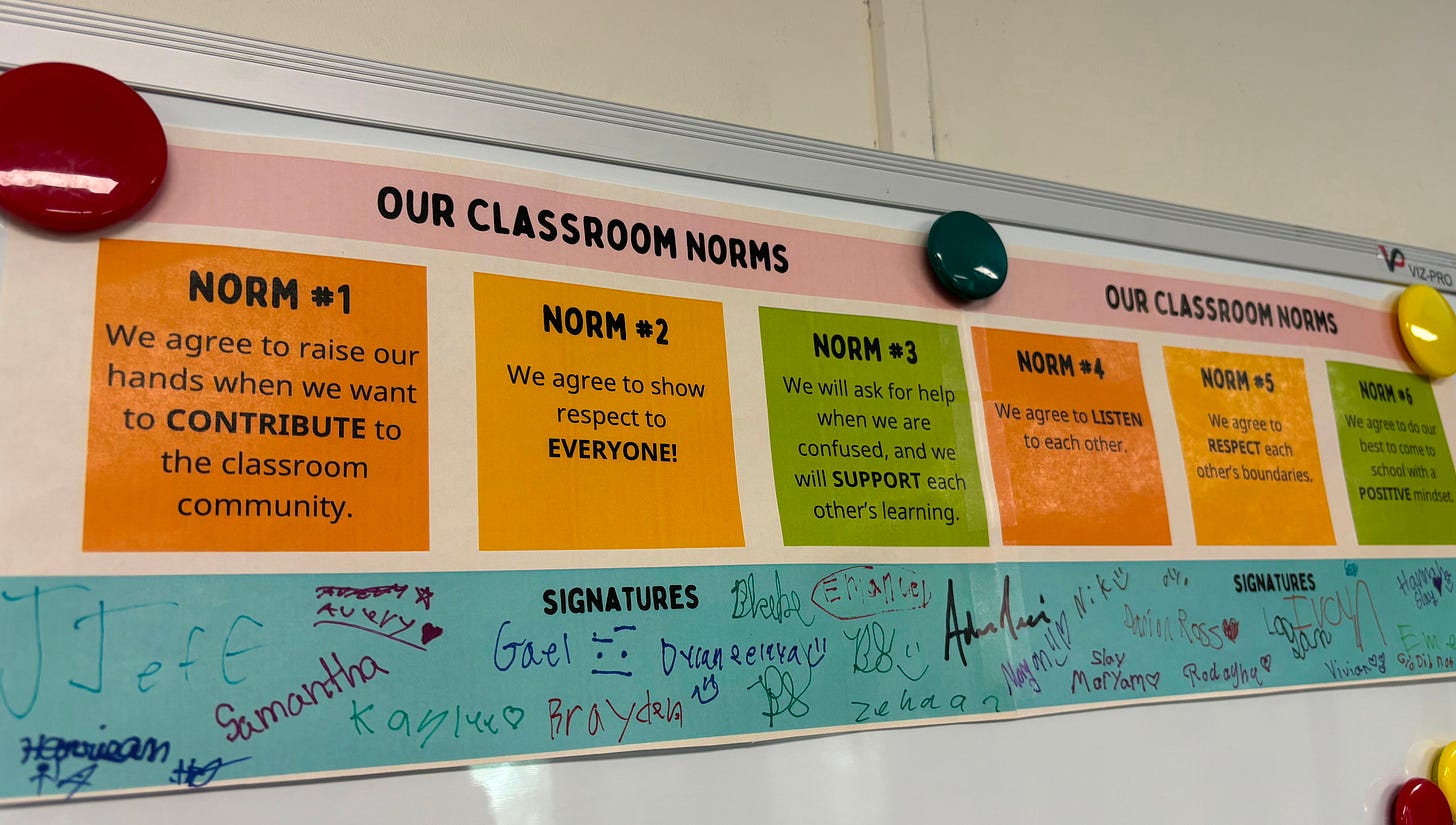

As a class, when we follow these core values, we create a classroom ethos of We over Me. The needs of the classroom community supersede the wants of the individual. When we work together to be successful fifth-grade students, everyone benefits, and everyone is more likely to get the support they need. It takes time to establish this at the beginning of the year because students come to me vying for my attention. We spend quite a bit of time practicing interdependence through jigsaw activities, productive group investigations, and team building. Over time, students begin to see that I may not be the best resource to support them. When everyone has a stake in everyone’s learning, academic growth is higher and more meaningful.

Compliance versus Reconciliation

Whenever I asked my father why I had to do something, he always said, Because I said so! I hated that answer as a kid and I still hate that answer today. My father demanded compliance and if I questioned his authority, I was punished. I was to obey him no matter what. I have observed classrooms where students are quietly sitting at their desks with their heads bowed over a worksheet. I mean, NO ONE is talking. The quiet is scary! It’s like everyone is frozen. A administrator may say, Look at their engagement! This is not engagement, this is fearful compliance. Even if I allow for the validity of the worksheet, learning is vulnerable and an innately social act. Compliant students who fear punishment, are not engaged. All this shows me is an imbalance of power.

My classroom has sociality at the center. I believe in building knowledge as a community and modeling intellectuality for my students during all of our learning experiences. I focus on building my students’ self-awareness instead of blind obedience. When conflicts arise and students make mistakes, I work to restore any trust that may have been broken. I model asking for forgiveness and seeking to make amends so that our community balance is restored. Rarely are conflicts so egregious that restorative practices cannot help. In those instances, I work independently with my students so that they are able to return to our classroom learning environment.

Either/Or versus Both/And

I grew up with good guys and bad guys; good and evil; right and wrong. These binary options limit the nuance of humanity. I vividly remember sitting in my red wingback armchair, reading the end to Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. When I learned about Severus Snape, I was shocked! He’s supposed to be the bad guy! He had been bullying and harrassing Harry for thousands of pages. My head was spinning weeks after finishing Deathly Hallows; how could a character be both a villian and a hero?

This is precisely what makes Severus Snape such a dynamic and interesting character. Snape never asked to be either a good guy or a bad guy. He made choices and had to live with the consequences of those choices, and that feels authentically human to me. In fact, Snape is probably one of the most human characters in the series because he secretly carries a both/and mindset throughout the novels. He holds his contradictory thoughts and feelings simultaneously, making him a rich and thoughtful character.

When I was a student, teaching and learning were either/or. If the teacher is right, then the student is wrong. There is only one correct way to solve a math problem. This type of learning environment never felt good to me (authoritarianism never does) as a student. Even with my privilege as a white, cis-gender, male, I never felt comfortable questioning authority, asking for clarification, or sharing my divergent thinking. Instead, I kept my head down and tried to give the teacher what she wanted.

As a teacher, I refuse to allow for binary pedagogical practices. I am not a perfect teacher who never makes mistakes, and I expect my students to hold me accountable with the collective wisdom in the room. Collectivist thinking requires contradiction. That is how democracy works. As a classroom community, we work to arrive at ideas and answers to the messy day-to-day business of teaching and learning. As a teacher, I may come to my students with more life-experience and expertise, but not necessarily more wisdom. I encourage my students to challenge my thinking in a respectful way in order to raise the rigor of our academic discourse. Contradictions can be uncomfortable, but we agree to sit in our discomfort, work toward consensus, and when necessary, accept non-closure. These values make for a richer classroom.

Time is Scarce versus Be in the Moment

At the beginning of summer, it takes me weeks to feel more like myself. Slow mornings makes it easier to feel more human; like I’m reteaching myself to be present.

During school, teaching can feel dehumanizing, like we are mechanized automatons programed to function in efficient minutes. Literacy: 120 minutes. Math: 90 minutes. Social Studies and Science: 60 minutes each. If I need to use the bathroom, I’m forced to calculate. Do I have time to make this copy and use the restroom? Probably not, so I’ll use the bathroom while students are silently reading. I hate it when we are having a wonderful discussion about what we are learning, and my eyes reflexively look at the clock to see if we have time for this discussion before transitioning to the next thing. It pulls me out of the present moment and into a never-ending scarcity loop.

Despite the common misconception that the rise of mass schooling led to the spread of industrialization in the 19th century, public education was not designed to support the Industrial Revolution. Training future factory workers was not the point of public education,1 though it can feel that way. Standardization reinforces a zero-sum game of minutes. If I take ten minutes to read aloud to my students, that is ten fewer minutes I have for my math lesson. Agendas, timelines, and curriculum maps are all used to keep school running in a timely manner.

The problem is that isn’t how life works. We all make space for unexpected things. I could be on my way to lunch with a friend when I get a flat tire and need to reschedule. One of the biggest lessons I learned from teaching during the pandemic is that you do not need 90 minutes for an effective math lesson. Learning takes time, but it can can be quick and occur in bursts. It is more important to me that I teach my students to be in the moment, then it is that I force them to understand a concept before the bell rings. I’m never on pace with our curriculum maps. If a specific concept takes longer to teach, so be it. If we go off topic, but grow closer as a community of learners, we will be okay. Wherever we are is where we are meant to be.

Transactional versus Transformational Relationships

Related to the zero-sum game of public education are transactional relationships. I will do this for you, if you do something for me. In transactional relationships, everything comes with a cost, including kindness. Transactions are embedded in the teacher expression, don’t smile until Christmas. If I smile too early in the school year, I am giving my students a kindness that they have not yet earned. Students must be obedient if they are to earn my generosity. These misguided values center teaching and learning for the purpose of completing a transaction as efficiently as possible.

Instead, I focus on building transformational relationships with my students. Students do not need to earn my kindness and respect; I give it freely. I build relationships, both internally and externally, based on trust, understanding, and our shared commitments. We may function within a system where time is scarce, but I make time for things that matter. There will always be time for learning and relationships.

There are many ways to decenter whiteness and white cultural values and habits. It is important to remember that dominant cultural values and habits can be internalized by people of all colors and ethnic backgrounds. We all need to know and use them to navigate society in U.S. dominate culture. I invite you to explore the resources below and deepen your understanding of whiteness, white supremacy, and intersectionality.

Have a great week!

— Adrian

Resources

How to recognize your white privilege — and use it to fight inequality | TED Talk by Peggy McIntosh

I can’t believe this TED Talk is over ten years old! Scholar and activist Peggy McIntosh discusses white privilege and how it can be used by those with power to ensure a fairer life for others.

White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack | Peggy McIntosh

This article was my first exposure to examining my own racial privilege. I highly recommend grabbing a journal and completing the mental exercise.

On the the last few pages are notes for facilitators who are teaching McIntosh’s work. These are interesting notes that I think make for a deeper reflective process.

Characteristics of a Dominant Culture

This PDF comes from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institute for Clinical and Translational Research. It is adapted from the work of Tema Okun, White Supremacy Culture — Still Here. I love the side-by-side comparison of dominant white cultural values and other ways of being. Here is another version of the same worksheet.

White Supremacy Culture | Tema Okun

Tema Okun’s website is chock full of resources for exploring whiteness, white supremacy and intersectionality.

Why Talk About Whiteness? | Emily Chiariello

Learning for Justice (formerly Teaching Tolerance) is my go-to resource for equity and social justice work to improve my pedagogy. This article by Emily Chiariello is a good starting point when asked the question, why are you talking about whiteness? Learning for Justice also has a toolkit for Why Talk About Whiteness here.

I’ve been using this video a lot in my work to create a positive racial identity, in myself and my students. Ali Michael, Ph.D., is the Director of K-12 Consulting and Professional Development at the Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education at the University of Pennsylvania and the Director of the Race Institute for K-12 Educators. She is the author of Raising Race Questions: Whiteness, Inquiry and Education, another book I highly recommend everyone reads.

The purpose of public education was general knowledge, citizenship, maintaining social order, and reinforcing obedience.

Tricky treasures….such a perfect phrase. Such a better description than the ones often used, and no doubt this group of treasures leans into the excitement of learning and curiosity. You are lucky to have each other.

“I mean, NO ONE is talking. The quiet is scary! It’s like everyone is frozen. A administrator may say, Look at their engagement! This is not engagement, this is fearful compliance. Even if I allow for the validity of the worksheet, learning is vulnerable and an innately social act. Compliant students who fear punishment, are not engaged. All this shows me is an imbalance of power.”

I say this in an attempt to expose my own areas for improvement and, hopefully, learn more…

The biggest example I see of this is in maths. The lesson ends with an independent task. The reason I prefer them to work alone is so I can see that they’ve done their own work and I can identify gaps. I think this is the right thing to do…

If I spend hours poring over the books to identify gaps.

In reality, I have a gist of what the children collectively need and we follow a scheme that works incrementally through the skills being taught at Year 6 level.

So, do I still need them to work independently on the worksheet at the end of a lesson? Can I get them to work together? Is that more likely to help the lower-attaining mathematicians develop in their arithmetic skills?

Help! 😂