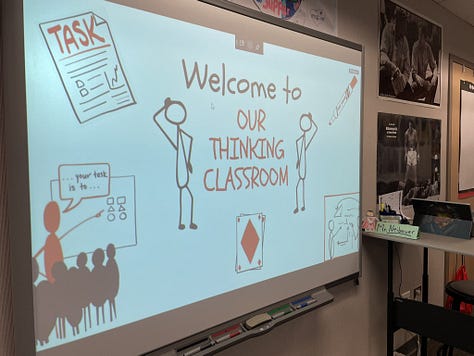

My Thinking Classroom

In the spring of 2022, our building’s instructional coach walked into my classroom and handed me a bright orange book. I just read this book and I think you will love it!

She knew that I had been feeling stale about teaching math. Although I had worked hard to make lessons and student discussions engaging, our district’s standardized mathematics curriculum left much to be desired. After years of teaching from the teacher’s guide, I was tired of my routine: teach a whole-class lesson from a workbook page, give students time to work independently at their desks, review answers, and assign another workbook page for homework. Repeat Monday through Friday.

By the time Spring Break arrives every year, I’m already beginning to daydream about what I might try for the following school year. Usually, this involves redesigning the layout of my classroom or reflecting on some of my previous learning experiences and tweaking them to make them run smoother. Every so often, I get a new idea and start designing immediately. My brain in March isn’t in a headspace to immediately begin teaching something brand new before June. So, I took home Dr. Peter Liljedahl’s book, set it aside to read over the weekend, and let it blend in to my large TBR pile.

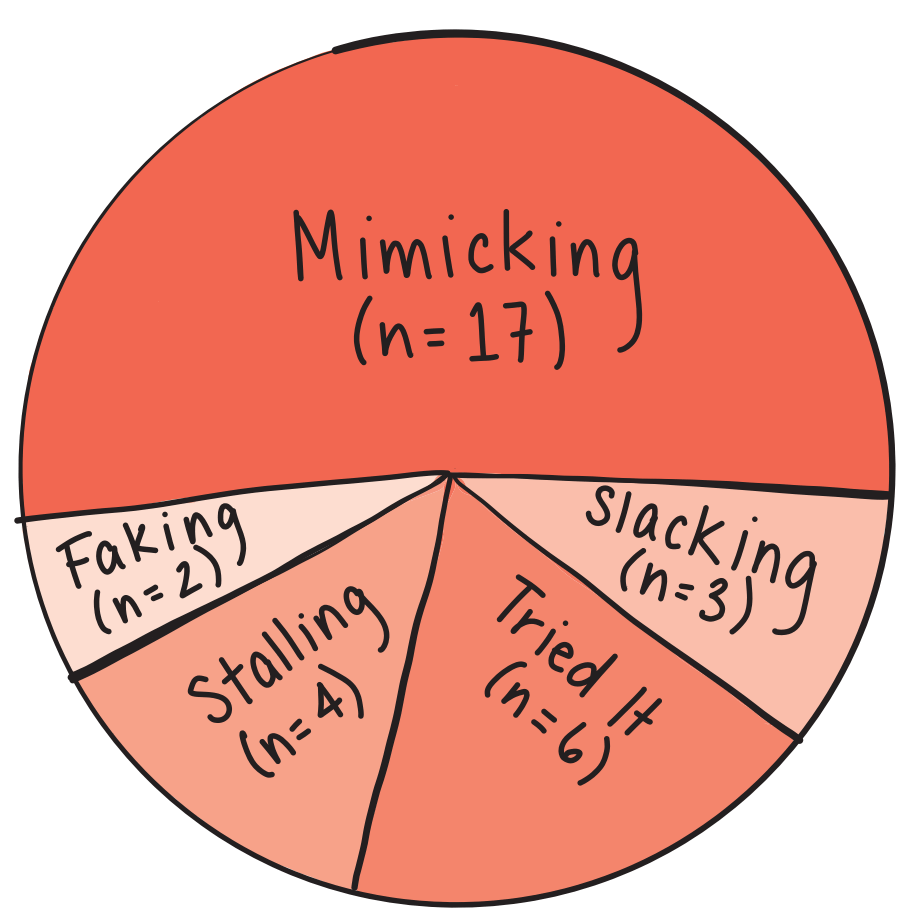

It wasn’t until the last weekend in March when I spotted the bright orange cover of Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics, Grades K-12: 14 Teaching Practices for Enhancing Learning and began reading. I read it over the course of an entire Saturday. I was hooked by Liljedahl’s premise: thinking is the precursor to learning and most students are not thinking in mathematics classrooms. At best, they are mimicking the teacher’s thinking at the front of the classroom. Learning math can be challenging, and when students don’t understand, it is easier to fake comprehension than to vulnerably engage with the struggle. Liljedahl observed 40 teachers teachers across 40 different schools and discovered a pattern: students were not engaging in critical thinking, but were instead mimicking their teachers during “now-you-try-one” tasks commonly known as “I do, We do, You do” tasks. This led to students having minimal short-term success and lack problem-solving autonomy or long-term mastery.1

This matched what I was seeing with my own students. As we worked through the prescribed problem-sets, a small number of my teacher-pleasing students would try the problems independently, but most would stall or avoid doing the work altogether. Once I reviewed the problems at the board, most of my class dutifully copied down my thinking into their notebooks. When it came time for an end-of-unit test, those same students would miss those exact problems they avoided during instruction and practice. In chatting with my students, I learned that they didn’t study because they felt that they knew the material. During the test, they claimed to forget how to do the problems. To me, it was clear: they never understood the problems in the first place. They were just mimicking my thinking and believing they understood the concepts.

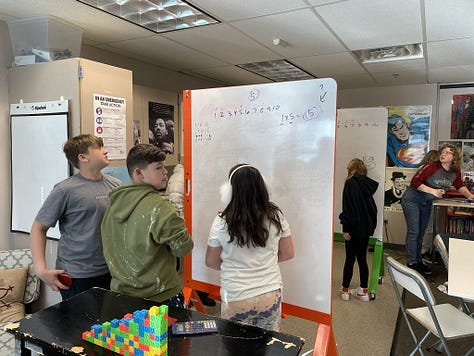

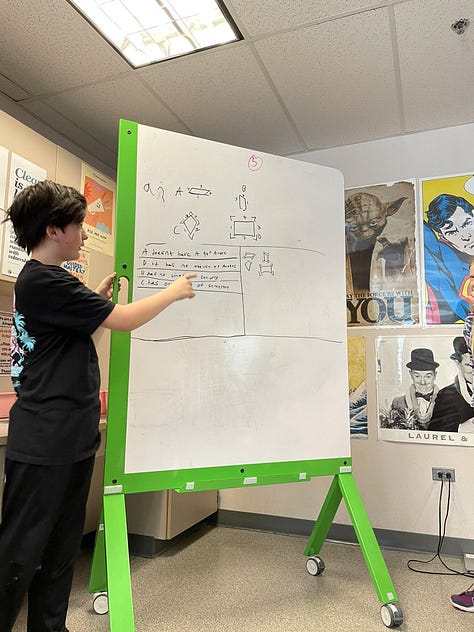

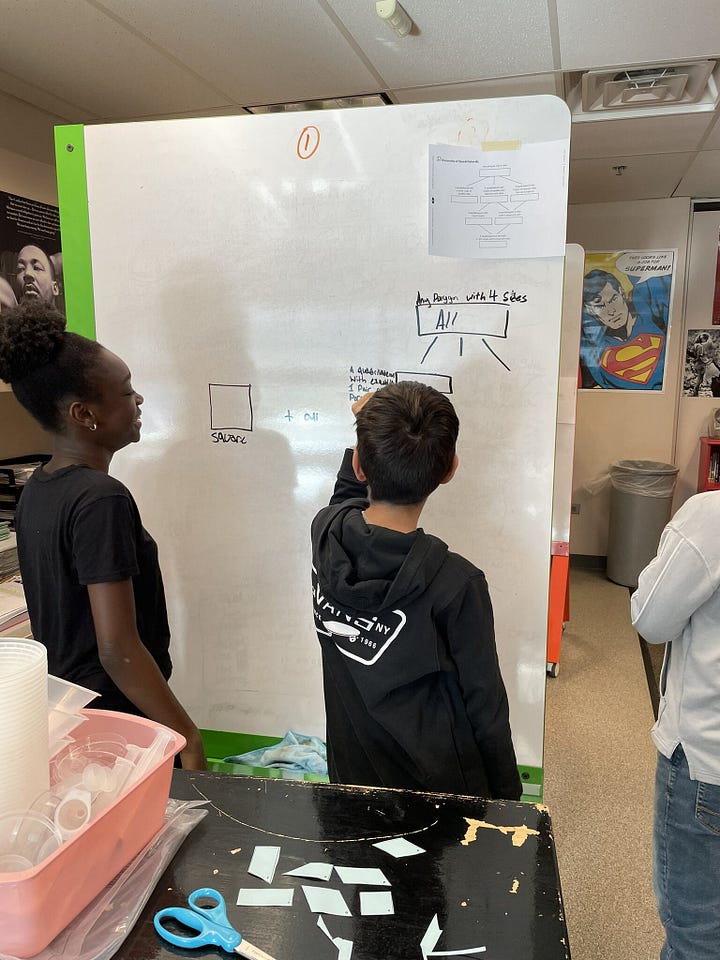

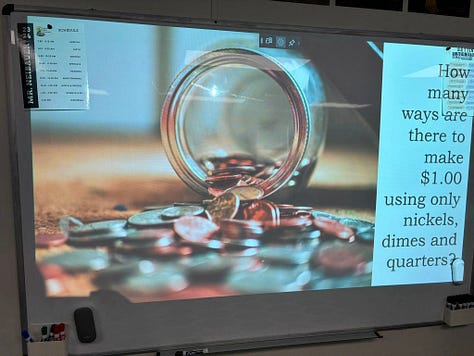

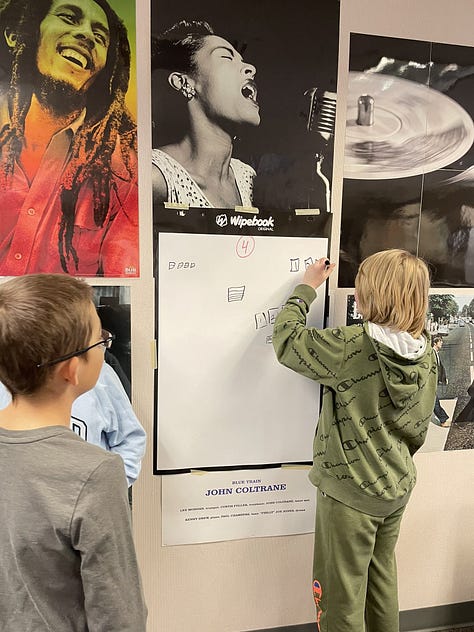

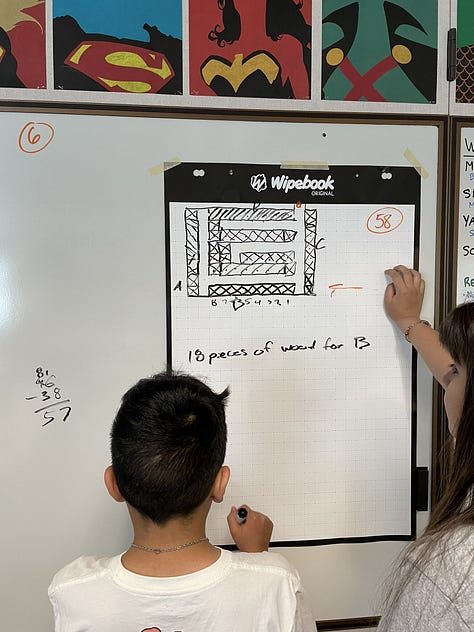

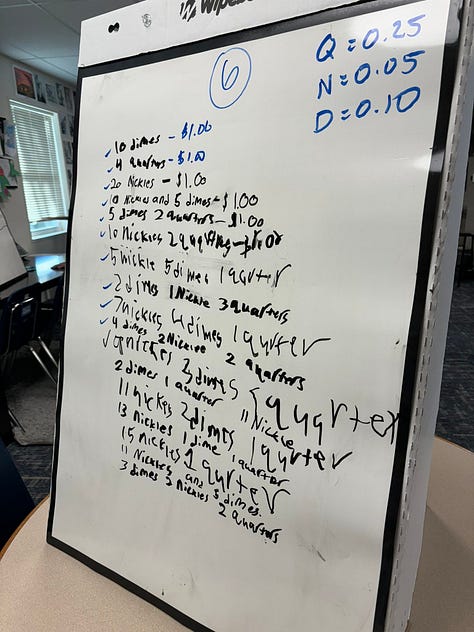

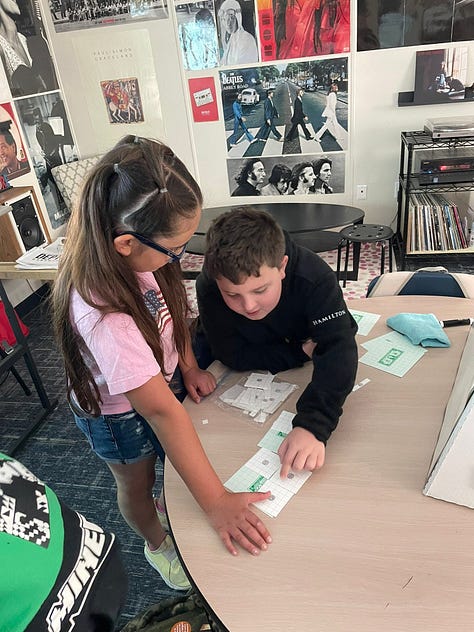

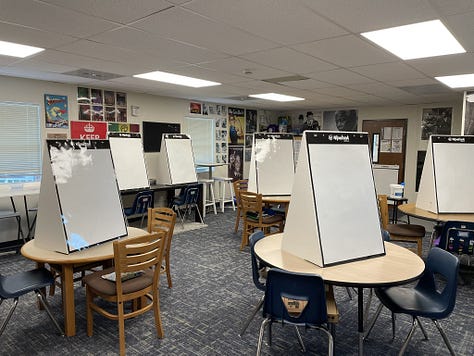

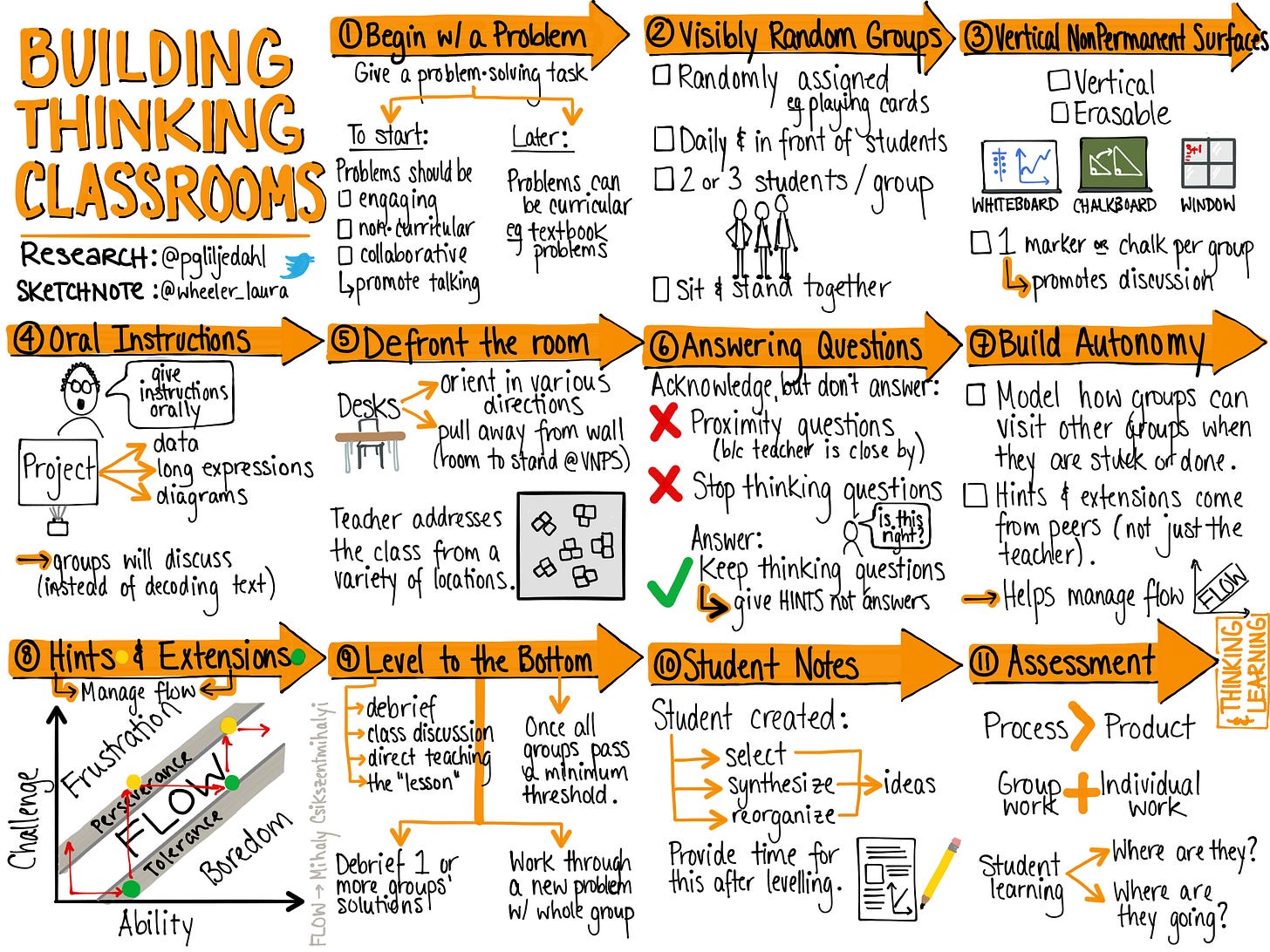

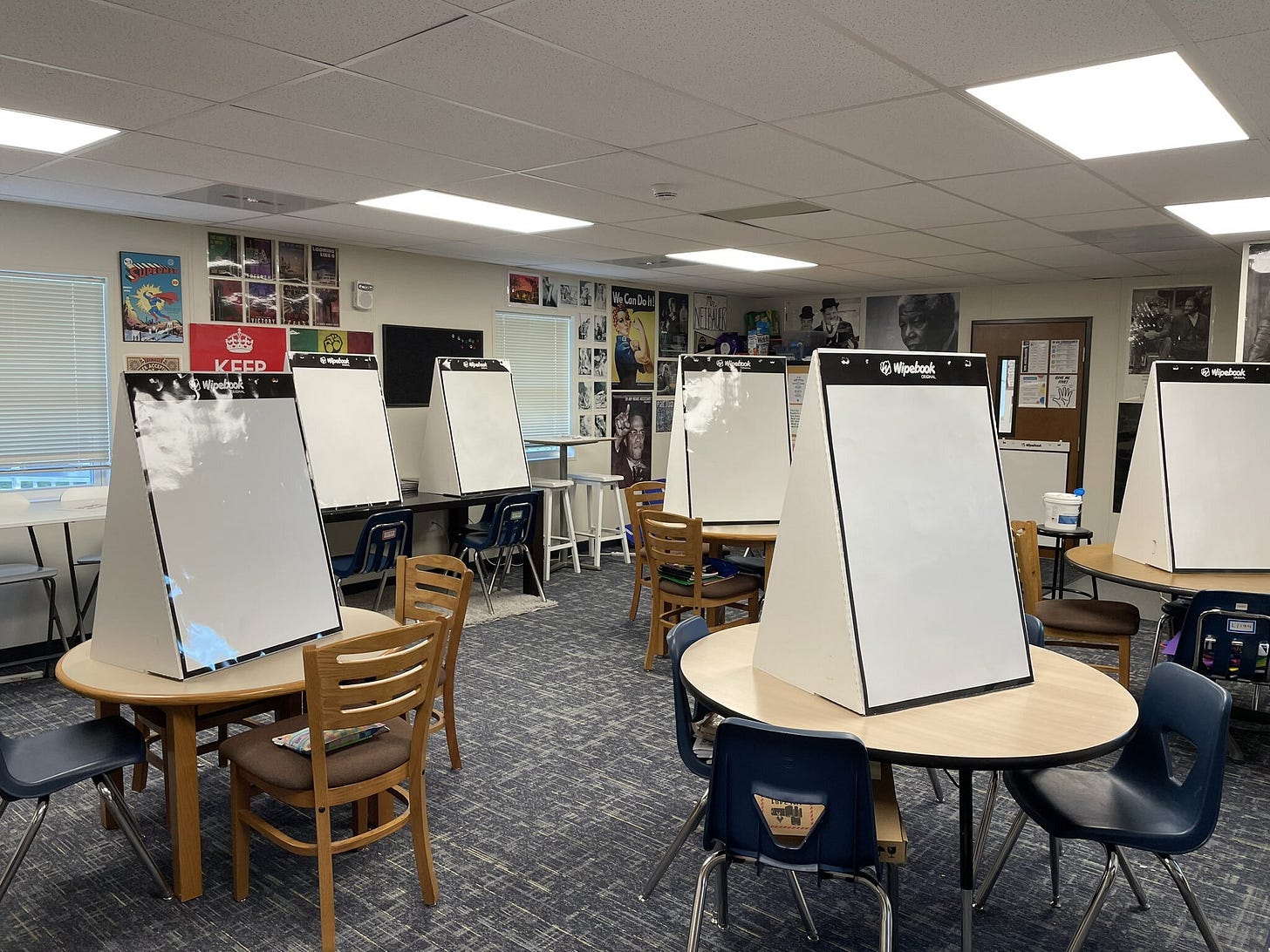

So, despite it being late in the school year, I decided to jump in and redesign my mathematics classroom around Liljedahl’s 14 optimal practices. Since he provides numeracy tasks and good problems for teachers to use with their students, the first thing I needed to get were some Vertical Non-permanent Surfaces (VNPS). Liljedahl found that when students are given a thinking task in visibly randomized groups, there is increased collaboration, improved student engagement, more dynamic thinking and group accountability, which leads to growth in mathematical thinking.

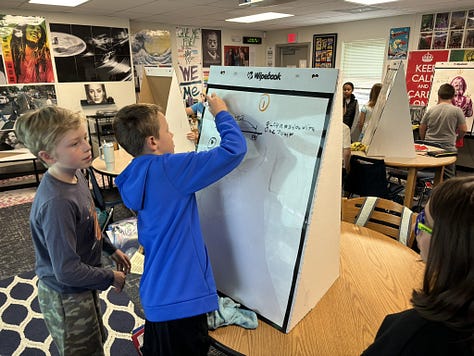

I found some old dry-erase boards in our building’s after school daycare. They were heavy and mounted on wheels, but I rolled them into my classroom, picked one of Liljedahl’s thinking tasks, put my students into randomized groups, and watched.

The first thing I noticed was how hard it was for my students to remain standing for an extended length of time. Liljedahl found that when students remain standing, they are more alert and less likely to disengage from mathematical thinking. Having fifth-graders stand for 30 minutes was a challenge2, but one I was willing to push through if it meant my students were more engaged and learning mathematics.

Throughout the rest of that school year, I found my students participating more in class and sharing their thinking. When students got stuck, I gave them hints and extensions to maintain the flow of learning. I pushed them to keep thinking through each problem until we were able to collectively synthesize their learning as a class, and then consolidate it into their math notebooks. Over time, I felt the energy of my mathematics instruction change. I was more engaged, and so were my students.

I have since been using Liljedahl’s thinking tasks and creating my own problems using resources from Rich Tasks - Math For Love, Math At Home, Illustrative Mathematics. Tap Into Teen Minds, Make Math Moments, youcubed, and GFletchy. Overall, I feel like my math classroom is more dynamic and engaging. I use a workshop model instead of a lecture format. My students are more curious about what they are learning and I believe they are thinking deeper about mathematics in general.

In the three years that I’ve been using Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics, I have learned a lot about what makes for an engaging and rigorous mathematics classroom. The main thing is that no strategy or system or program or book is perfect. In fact, there are plenty of skeptics that question the validity of Liljedahl’s research.3 While I have been following most of his guidelines for creating a thinking classroom, I have not adhered completely. In fact, I have yet to master his grading practices and I don’t consolidate the mathematical concepts in the exact way he suggests.

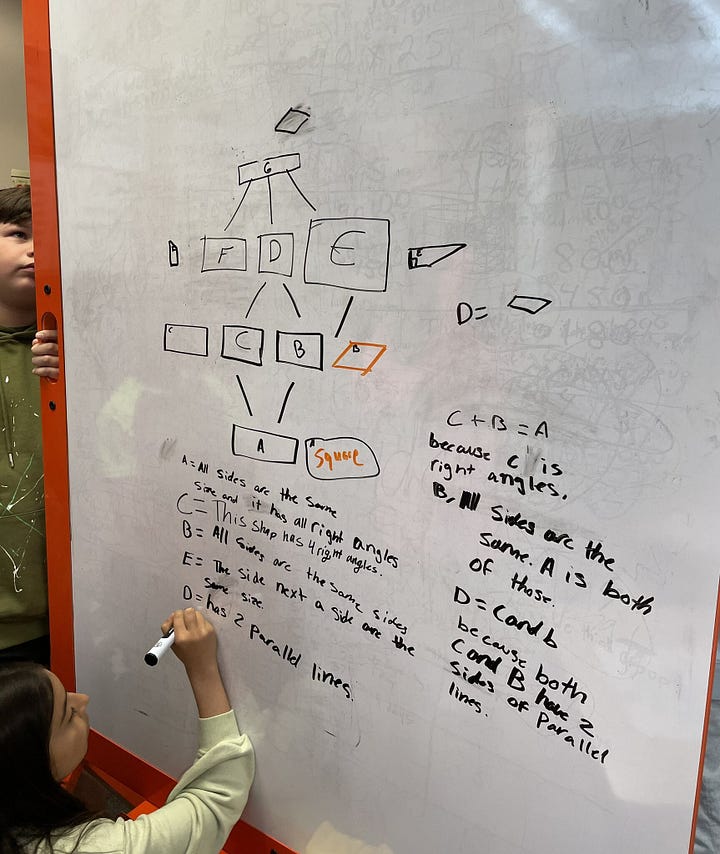

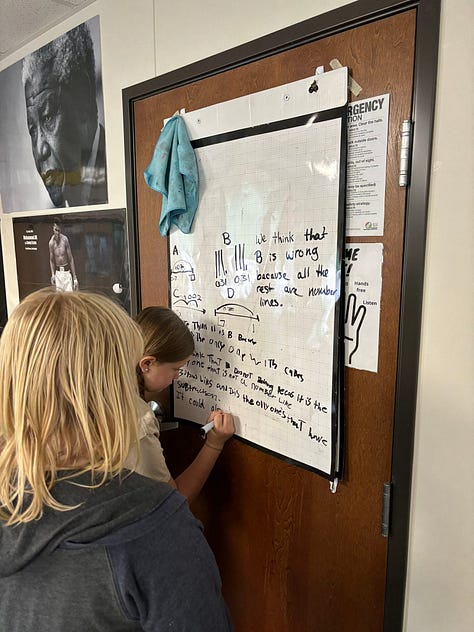

In a thinking classroom, consolidation takes an opposite approach—working upwards from the basic foundation of a concept and drawing on student work produced during their thinking on a common set of tasks.

I find that what works best for my students is to tailor his 14 practices to the needs of my students, and base them on my own pedagogy and our shared experiences collaboratively learning. I take what I like and what works, and leave the rest.

Take what you like and leave the rest.

We have 75 minutes for math. Our thinking tasks usually last for 30-40 minutes depending on the day or problem. During this time, I visit each group multiple times offering hints and extensions. I reserve the last 10 minutes of class to bring students back to their desks and record our collective thinking in their math notebooks.

Here is a snapshot of what my Thinking Classroom looks like during the week.

Monday

My math block is first thing in the morning. Since Mondays are always challenging for my students, I begin every day (especially Mondays) with a soft start. We don’t begin math until everyone has eaten breakfast and had time to share their weekends and adjust to being back in school. Once I share some announcements, I break students into their randomized groups and transition them to their easel whiteboards.

Tuesday

On Tuesdays and Thursdays, when students enter the classroom, there is usually a workbook page assigned for them to start working on while they finish their breakfast. Whether you call it a Warm Up or Bellwork/Bell Ringer or Do Now, having a few problems for students to work on gives me time to socialize, take attendance, and prepare for the upcoming thinking task. I never expect students to complete an entire worksheet, but instead, want them to pick 1-2 problems that will help them get ready for our upcoming task. After some independent/collaborative work time, I review the answers to the warm-up and have a few students share their thinking with the class.

The first half of this time-lapse video shows a typical Tuesday or Thursday morning.4

Wednesday

Wednesday is a shortened school day for everyone. School dismisses an hour early for staff meetings and professional development, so I don’t have a full math block. Instead of trying to cram a thinking task into the morning, I reserve Wednesdays for taking notes. This Note Day is my chance to make sure that students have written down in their math notebooks some important concepts, formulas, or diagrams/pictures from the concepts we have been learning throughout the week. This very much goes against Liljedahl’s recommendation of having students write their own notes to their future forgetful selves. I appreciate his strategy, but since I plan to have students use their notes on their math tests, I want them to have a combination of their own thinking and the concepts, formulas, or pictures that I feel are important. It may be mimicking, but I allow it for one day so that students practice taking notes and asking questions.

Thursday

Thursdays look similar to Tuesdays. The bell rings. Students enter. The directions on the board tell them to begin their warm-up. We review said warm-up and students begin collaborating on a new thinking task. I try to have each thinking task build on the one before, leading to the content standards I teach throughout the unit. When our warm-ups dovetail with the thinking task, it makes for a nice learning flow.

After 30-40 minutes of students collaborating at their easels, I bring everyone together to synthesize the thinking in the room. Students take turns sharing their group’s thinking. I let this be student-led, giving them minimal guidance of what they should attune to and write down when they return to their seats and math notebooks. Liljedahl calls this a levelling process where teachers highlight particular parts of the work on the boards and students select for themselves what they record in their notes.

Friday

On Fridays, I do not have a formal thinking task planned. Instead, I have students work independently to practice specific mathematics skills we have been learning. I meet with small groups to reinforce instruction from the week. Students can choose to work independently on Khan Academy, ST Math, or Zearn Math. Some choose to work in their math workbook, but most choose one of the gamified programs. This year, I have been lucky to co-teach with an English Language Supports (ELS) specialist and a Neurodiverse Gifted & Talented (GT) teacher. Instead of only working with their specified population of students, I encourage them to lead small groups of any students who need extra support in mathematics. Having more adults helps a lot!

Even if I am not following Peter Liljedahl’s Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics to the letter, I am grateful for how these thinking tasks have reinvigorated my teaching. Since publication in 2020, Building Thinking Classrooms has exploded in popularity among teachers and school districts. He has partnered with Wipebook to offer discounts on their dry-erase flip charts and easels. I don’t know whether this method of teaching mathematics will last in ten years or if the science of learning completely supports it, but I do know that it is working for me and my students. Despite continued complaining about having to stand for 30-40 minutes, and some students wandering away from their randomized groups, I see more engagement and growth in mathematics. I’m not trying to put myself in the middle of The Math Wars. I’m continually learning and improving as a teacher of all subjects. As a math teacher, every time I learn something new, (e.g.: instructional hierarchy framework to improve student learning) I try to incorporate it into my ever evolving pedagogical practice. This is the work of teachers. There will never be an endpoint when I’ve learned it all and can confidently call myself the best teacher. Instead, I choose lifelong learning, taking what works best for the students in front of me, and leaving the rest.

Have a great week!

— Adrian

Resources

The Thinking Classroom: An Interview with Peter Liljedahl

This is probably one of his best interviews about thinking classrooms. Jennifer Gonzalez asks probing questions about the application for this method and what it could look like in different settings. Recently, Liljedahl published a supplementary book, Mathematics Tasks for the Thinking Classroom, Grades K-5.

Here is another great piece written by Michael Pershan that offers a counter-perspective. It may even explain why I glommed onto Liljedahl’s book so easily. I appreciate how Pershan doesn’t provide all the answers; just great questions!

In this video, teachers explain the basic mechanics of a thinking classroom. One modification I have made is to provide students with specific roles in their groups and model for them certain habits of discussion.

Tim Brzezinski has created an incredible resource for those teachers wanting to teach Thinking Classrooms properly. Liljedahl has an entire chapter dedicated to grading in a thinking classroom and Brzezinski’s video outlines his Google Sheets gradebook that he uses when assessing his high school students.

In this episode, Liljedahl speaks to consolidating in a thinking classroom. His examples are very clear and push me to improve this aspect in my own classroom.

This is such a great episode! After listening to SpringMath founder, Amanda VanDerHeyden, I’m going to incorporate more mastery work in my math classroom so that students can achieve mastery on discrete skills, helping them learn more complex tasks and generalize and apply learning to problem solving.

If you want a deeper discussion of The Math Wars, check out this episode on The Disagreement podcast. Holly Korbey from The Bell Ringer and Kevin Dykema (President of National Council of Teachers of Mathematics) are guests.

Even when starting the year with thinking tasks, this still remains a challenge for my students. They just want to sit down!

I particularly liked reading Michael Pershan’s analysis of Liljedahl’s research because it gave me pause when thinking about how a curriculum becomes “evidence-based.” I have also found other teachers who question the vilification of mimicry as a learning strategy.

The second half of the video shows us transitioning into our writing workshop.

Really like your statement that you're not sure if it's scientifically supporter or if it will stick around, but it's working for you. Amen. That book is basically an action research project and you applied those ideas, the way it's supposed to work. If we wait to "prove" stuff in education we'll never help the students we teach now. And truthfully, we'll never be able to construct an experiment to prove anything in classrooms--too many variables plus some ethical issues--so be intententional, collect data, report with integrity and we'll move the needle one classroom at a time. Thanks for writing this piece!

What a wonderfully dynamic classroom you've got, Adrian! The movement that goes on in your Tuesday and Thursday mornings is properly inspiring.