A New Student

Welcoming the Newest Member of our Classroom Family

I have experienced 24 first days of school as a teacher. Before that, from Kindergarten to the first day of my doctoral program, I have had another 43 first days of school.1 Being a new student in a new class is exciting and scary. If you are lucky, you may see a familiar face from a previous class, but the majority of your classmates are strangers. You know nothing of them or your new teacher. You show up with a bag of school supplies as prepared as you can be for the start of a new year of learning. In K-12 classes, the first day is a liminal space: on paper, you are officially a fifth-grader, but on the first day of school, you are no longer a fourth-grade student, but you are not yet identifying as a fifth-grade student. Sitting in your seat, between past grade levels and present classrooms, you often feel uneasy; stomach butterflies and sweaty palms. Standing in front of a new batch of students as a teacher feels equally unnerving. On the first day of school you welcome your students, waiting in suspense, to a new year.

Moving to a new school once the school year has already started, and walking into a classroom that is humming with ritual and routine, is particularly challenging. It is like walking into a theater once the movie has started, trying to figure out what has happened, who the characters are, all while trying to follow the plot. Welcoming a new student during the school year can feel jarring to the flow of the classroom community. They may walk in during the middle of a science unit or three-quarters of the way through a read aloud or novel study. New students come with their previous classroom experiences with which they hold in comparison to their new class. Whether it is August or October, being a new student in a new school is scary.

I like to onboard my new students. Instead of showing them to their desk and shoving a bunch of textbooks in their face, I interrupt all classroom activities to welcome them as the newest member of our classroom family. I always prepare my students ahead of time, letting them know we will be getting new student in the coming days. Depending on how much notice the front office gives me ahead of their arrival, I have my students make welcoming gifts. These can be simple construction paper signs or cards that say WELCOME! If we have a lot of time to prepare, I will accept student volunteers to show them around the classroom and explain how our Mr. Neibauer runs things. Students love being docents, guiding a new student, answering her questions, and giving her insider information about the school building. Having a new student is an opportunity to strengthen the existing classroom culture.

Last week, I received a new student from another country. I found out I was receiving a new student only after we returned from a field trip the day before, so I had no time to prepare my students, except to tell them that our newest classroom family member would be arriving tomorrow. It is important for all of my students feel like they belong in our classroom, so I stayed after school creating a simple onboarding package of stickers, fun erasers, a bracelet with the school logo, and a tee shirt from our feeder high school. I made a welcome sign and set it up at her new seat before calling it a day.

I arrived early the next morning to tidy the classroom and ensure everything was set for her arrival: directions on the board, music playing on the turntable, extra school supplies at the ready, and me stationed at the front door with my cup of tea in hand. When she arrived, she was immediately surrounded by ten girls who escorted her to our classroom. I had barely introduced myself when the girls took charge of helping her unpack, open all of her school supplies, and label everything. While I was saying good morning to the rest of my students, the girls were busy making sure she was ready to start class before the bell rang. I sat back and watched as my newest student was warmly enveloped by the rest of the class. Everyone participated, delegating responsibilities to each other. I was even sent to get the supplies bin I had forgotten.

School started. I discussed the upcoming day and introduced our new student to the class. We transitioned to our morning Family Meeting, sitting in a circle on the floor. My original plan was to debrief the previous day’s field trip, but watching how my class welcomed our newest member, I knew what we needed to discuss.

Let’s go around the circle. What is one thing you think J needs to know about our classroom?

One by one, students shared their tips and tricks for navigating Mr. Neibauer’s fifth-grade classroom. Some shared about how she could get a Jolly Rancher candy. Others shared our familiar routines. One student stood up to show her our classroom agreements. And still another student warned her about Mr. Neibauer’s triggers. By the time it was my turn to share, I had nothing. Without preparation or prompting, my students had completely welcomed our new student into our classroom community.

Natural Caring

Children are naturally caring. Nel Noddings, American feminist, educator, and philosopher, argues that “compassion is a quality shared by all individuals” and that to be a caring person is to act morally. In her Theory of Care, Noddings emphasizes four elements of ethical caring: engrossment, compassion, motivational displacement, and reciprocity. Engrossment defines the ways in which the one providing care is present to the needs of the one receiving care. Engrossment requires mindful effort.

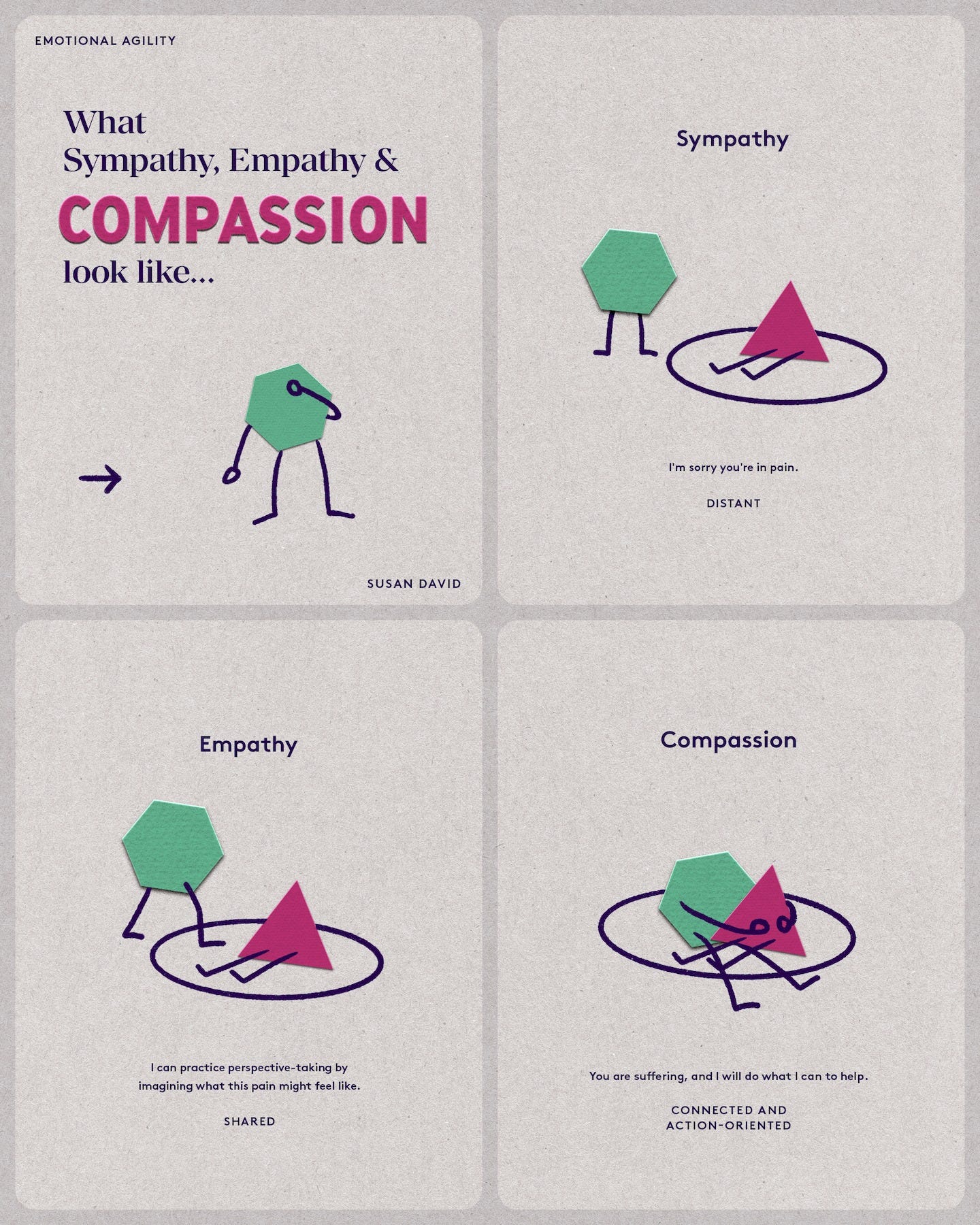

As I watched my students surround our new student, they were exhibiting engrossment. They recognized our new students’ needs and set out to fulfill them as best as they could. Seeing our new student smile, assured me that she was receiving these actions as caring, not controlling. This is compassion at its most pure. Susan David, author of Emotional Agility, defines compassion as being connected and action-oriented: I see that you are suffering, and I will do what I can to help. While my new student was not overtly suffering, she was nervous about being in a new country, coming into a new school, and walking into a new classroom with new people. My students instantly recognized this and set out to help her adjust as quickly as possible.

Noddings believes that natural caring for another also requires motivational displacement, the carer’s motive energy flowing towards the cared-for. Noddings expaings, “When I care, my motive energy begins to flow toward the needs and wants of the cared-for.”2 Therefore, the carer responds in a helpful way to the cared-for.

It was clear watching my students help our new student that their motive energy was actively flowing. All they wanted to do in the ten minutes before the bell rang was to make sure that their newest classmate was prepared for the day ahead.

Finally, Noddings explains that the one being cared for also has a role in a caring relationship. This “recognition or realization of care” (termed reciprocity) is how the cared-for indicates that caring has been received. Reciprocity does not need to be verbalized. When the bell rang and J, our new class member was seated and ready, I could easily see that she knew she had been cared for. The warmth she received from her classmates emanated from her. She may have still been nervous, but she was happy.

Noddings believes that natural caring interactions are essential to human life. I believe that natural caring is essential to academic achievement and student learning. If students are to learn, they must first feel safe and then cared for. Otherwise, teaching and learning become dehumanized practices in a dehumanized space.

We should want more from our educational efforts than adequate academic achievement and … we will not achieve even that meager success unless our children believe that they themselves [sic] are cared for and learn to care for others.

Nel Noddings, Teaching Themes of Care

Forming caring relationships with 30+ students at the elementary school level, and 100+ students in grades 6-12, is a daunting task. Public education, in its current state, does not allow the inclusion of themes of care in the curriculum, nor does it allow time for teachers to address the social-emotional needs of their students. Raising test scores remains the sole priority of school districts, expressed by administors and school boards. Money and resources are continually dumped into standardized test preparation, so-called high-quality instructional materials (HQIM), and professional development designed to dehumanize and standardize the classroom environment.

Care need not be time-consuming. The amount of care I witnessed in the first ten minutes of the school day was impressive; and yet, the responsibility never fell to just one person. Everyone participated, contributing a small amount of care, making the collective experience great. Throughout the rest of the day, whenever our new student had a question, she knew who she could turn to, and it was not always the teacher.

I do not need to establish a deep, lasting, time-consuming personal relationship with every student. What I must do is to be totally and non-selectively present to the student – to each student – as he addresses me. The time interval may be brief but the encounter is total.

Nel Noddings, Caring, a Feminine Approach to Ethics & Moral Education

I wish public education was structured with care at its center. Noddings believes that “care must be taken seriously as a major purpose of school” and that “caring for students is fundamental in teaching; developing people with a strong capacity for care is a major objective of responsible education.” Unfortunately, what I mostly see, under the guise of care for teachers and students, are platitudes and shallow lip-service to improve the mental health of staff and students. Self-care BINGO cards and bags of Skittles in teachers’ mailboxes with pinned notes saying, Over the rainbow GRATEFUL for you, do not show natural caring. The intention here is not the same as the impact.

Noddings argues that education from a perspective of care requires four explicit behaviors: modelling, dialogue, practice, and confirmation. I may not explicitly teach my students lessons on care, compassion, and empathy. However, my daily interactions with students make clear that care is a central part of my pedagogy. I model for my students what it means to care for them. I show them that I care in my attentiveness to their needs and how I advocate for their well-being in the classroom. I openly dialogue with my students about care and caring for each other. I repeatedly tell them that I care about their success in my class and in life, and that I care about them as human beings. As a class, we regularly engage in caregiving activities to develop students’ individual and collective ability to care. Noddings states, “If we want to produce people who will care for another, then it makes sense to give students practice in caring and reflection on that practice”, and so I give my students daily practice being a caring individual. From cleaning up at the end of the day to helping each other out in small groups, I remind my students that we are a classroom family that cares for each other. Finally, I try to always give my students the benefit of doubt in their actions. This is what Noddings refers to as confirmation. A successful caring relationship between me and my students depends on the relationship between the cared-for and the carer. Sometimes I am doing the caring for my students, and at other times, students are caring for me. It is this reciprocal relationship that matters most. All of the other stuff — the challenging weeks, the basal textbooks, the recalcitrant behaviors, the disengagement from learning — is spherical to care.

When our new student arrived, I witnessed Noddings’ care ethics in action, and I could not have been more proud of my students. I am confident that my new student will fit right in with our caring classroom community.

Have a great week!

— Adrian

Resources

This hour-long interview with Nel Noddings is well worth your time. If you are pressed for time, watch this clip, Teaching for More Loving Human Beings.

On May 4, 2010, Dr. Nel Noddings visited Arizona State University to speak with graduate students. This entire interview, albeit lengthy, is wonderful. If you are looking for just one clip to watch, I suggest Part 4: Education is Not a Race. However, if you have the time, I’ve linked each Part below.

Alfie Kohn: The Caring Subversion of Nel Noddings: An Appreciation

From the beginning, Noddings has been a fierce critic of standardization. “The worst feature of current moves toward standardization, is the insistence that all kids meet the same standards, regardless of their interests and aptitudes.” This short blog post by Alfie Kohn is a great read.

How to Create a Culture of Care in Your School: Lessons From 10 Years as Principal | Education Week

I always appreciate with administrators make clear exactly what they do to improve the culture of their school buildings. This piece by former principal, Matthew Ebert, has great suggestions for creating a culture of care in your building.

How Teachers Can Make Caring More Common | Harvard Graduate School of Education

Again, I love reading concrete ways to create a climate of mutual respect and caring in my classroom. Harvard’s Graduate School of education outlines very tangible steps for creating a more caring environment, as well as as some great resources for teachers to improve their pedagogy.

Not counting all of the first days of each individual class I took in high school and college.

Noddings, N. (2005) ‘Caring in education’, the encyclopedia of informal education, www.infed.org/biblio/noddings_caring_in_education.htm.

What a teacher you are and what a caring classroom you’ve cultivated! 💕

Love this--and thanks for the video resources!