Opting Out

My annual standardized testing philosophical crisis.

I’m a hypocrite. For decades, I’ve never put credence on standardized testing. I’ve always supported my students opting out of their annual battery of tests. I see very little value in spending three weeks stressing over a number on a test, which will bear very little fruit in the future. I do litle test preparation, aside from showing my students the platform they will be testing on, and making sure they know how to use the tools. Do not be fooled. I place no value on the outcome of these tests, but I take standardized testing seriously. Very seriously. I have no choice. My livelihood as a teacher depends on my students scoring well. When I transform from human teacher to draconian proctor, it feels terrible. I try to bolter my students with speeches: if you can’t get out of it, try to get into it.1 But it sucks. The banality of standardized testing is very real.

Yet, as a parent, I’ve always forced my own children to take standardized tests. I’ve convinced myself that I want to know how my children are performing, even while simultaneously knowing that the results do not accurately represent my children’s intelligence. I tell myself that I want my children to do hard things because in life, we have to do hard things, even when we don’t see their value. We can’t opt out of life.

Since my children were old enough to test, I’ve straddled the line between parent and teacher. I have always supported my children first. I’ve taught them to be good students. Play the game. Learn the stuff. Get the grade. In the past, what has been best for my children coincides with what is best for my students, and vice versa. No more. I proctor my students, pushing them to take their locked down tests in earnest, but internally, I’m struggling to find the point of it all. My rose-colored glasses are cracked and dirty. I’m struggling to see the benefit for any child to suffer these tests.

My children are old enough now to see this transactional facade. Do grades really matter if I’m not going to college? Do I need to go to college? I’ve taught them that if they learn for the teacher, they will also be learning for themselves. And that is enough.

Standardized testing culture tells my kids (and students) it isn’t enough. You must also perform well on these tests to prove you learned. No test score. No proof. No learning.

So, when my teenage son and daughter pressed me once again to opt them out, I reluctantly resisted. I reiterated how the test may not be important to me or them, but the school and district needs those scores for funding. Teachers rely on standardized test scores to legitimatize their teaching to administration. As teenagers are prone to do, especially teenagers of a teacher, they poked holes in my hollow rhetoric.

This hard thing I’ve been making my children do in the name of abstract accountability and funding they will never see, has been causing them real harm. Both of my children are dyslexic. My son has internalized such a deficit mindset that he believes he is retarded.2 Years of standardized testing have not only reinforced how stupid he feels, but have convinced him that he won’t be successful outside of school. My daughter, overwhelmed by the pressures of testing, calculated that the cost of these tests on her mental health did not outweigh the benefit of a meaningless score.

I eventually capitulated and opted both of my children out of their tests, and then woke up the next morning to proctor another round of standardized tests for my students, forcing them to take the tests seriously, encouraging them to try their best and show them what you know. I have fewer parents opting their children out this year. Perhaps it’s because of the latest rebranding as a “great opportunity to take timed standardized tests, which benefits [students] when they are taking ACT, PSAT, SAT or AP exams.” Maybe it’s the testing parades our school organized in order to rally students behind taking 15+ hours of tests. My daughter’s middle school provided “special treats” and a “choice activity” to all those who took the tests, which “provide the school with a lot of data on how teachers can continue to serve all students.”

I’ve seen firsthand, the results of opting out of standardized tests en masse. Students, post-pandemic, now see so many aspects of learning as optional. From appropriate school behavior to productive academic struggle to conflict resolution, students have grown accustomed to having a choice not to comply. Why obey the teacher or follow the school rules when there are little to no consequences for my actions? Why try hard on this math problem when the teacher will just move on whether I understand it or not? Why struggle to read when I can just watch a TikTok summary? Given the easy way out, most people, especially kids, will take the path of least resistance and more screen time dopamine.

I worry that by providing so many opportunities to opt out, we’ve atrophied students’ ability to engage in the discomfort of learning. Not all learning is instant gratification. Most things, especially those that matter, take time and work to fully understand. I don’t want to call my students lazy, but they don’t see a point in engaging in any struggle. Learning requires struggle. I’m honest with my students. I tell them that at some point during the year, they will struggle. The struggle isn’t the place to stop and give up, but instead, the point at which I want them to settle in; to be habituated with their discomfort because that is where their learning and growth happens.

Dan Siegel, a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, calls this the Window of Tolerance. It is used to describes the optimal state of stimulation in which we are able to function in everyday life. When we exist within this window, we are able to learn effectively, play, and relate well to ourselves and others.3 On either side of the window, one can enter hyperarousal or hypoarousal. Hyperarousal is characterized by anxiety, panic, or anger. Your body is in fight-or-flight mode, with symptoms like rapid heartbeat, quick breathing, and muscle tension. It’s a survival response to perceived threats. Hypoarousal involves low energy, numbness, and disconnection. Your body is in a state of conservation, often described as a shutdown in response to overwhelming stress or trauma. Unfortunately, I’ve seen more and more students come to my classroom emotionally dysregulated and unable to learn because of previous trauma.

Post-pandemic, I’ve also seen more students unwilling to engage in any sort of academic struggle. In some cases, my students suffer a learned helplessness where they have internalized continuous messages that they’re destined to fail. In far more cases, though, my students don’t see the point of engaging in any struggle whatsoever. They are used to an educational system that will push them through whether or not they can read at grade level. I realize that there are a myriad of reasons explaining my observations. From learning loss to a collective crisis in adolescent mental health fueled by an addiction to screens, students are disengaged and uninterested in trying.

This is most evident during standardized testing season. In the last five years, I’ve seen high school seniors boycott testing by opting out in droves, and increasing numbers of parents of elementary school students choosing to opt out each spring.

As a parent, I appreciate my children’s ability to advocate for themselves, especially when it goes against what the school system is telling them. I’m not worried about my children giving up when things are hard. Dyslexia makes many aspects of learning challenging, but my children are lucky. In our household, we value dyslexic thinking.

Very early, my children learned that they would have to work harder to make the same gains in school as their classmates. While my son still struggles with having a positive academic identity, my daughter defies anyone who stands in her way. We work hard at home to counter the deficit messaging they hear at school. We value their brilliance.

As a teacher, I worry about the message we’ve collectively sent to our students: if something is too difficult, or you don’t like it, you can opt out. And so I now find myself in a strange situation: simultaneously supporting my own children in opting out of their standardized tests, while using incentives and empty rhetoric to motivate my students to not opt out and get a high score on their standardized tests.

“If there is one unavoidable truth in this world, it’s that there is no substitute for putting in the work. Working your ass off is the only thing that works 100 percent of the time for 100 percent of the things worth achieving.”

I’ve always tried to follow this maxim. My German-immigrant grandmother was the hardest working person, I’ve ever met. She was illiterate and showed me, through example, the satisfaction of working hard and fully completing the jobs she had to do. From growing her own food, to cleaning her home, to working evenings cleaning the local bank, she never half-assed anything! As a teenage runner, I was not the fastest, but my work ethic set me apart from my teammates. I put my head down and got to work. As a struggling student, I learned that even when I struggle or dislike a task, I try to give 100 percent because doing otherwise falls outside of my system of values.

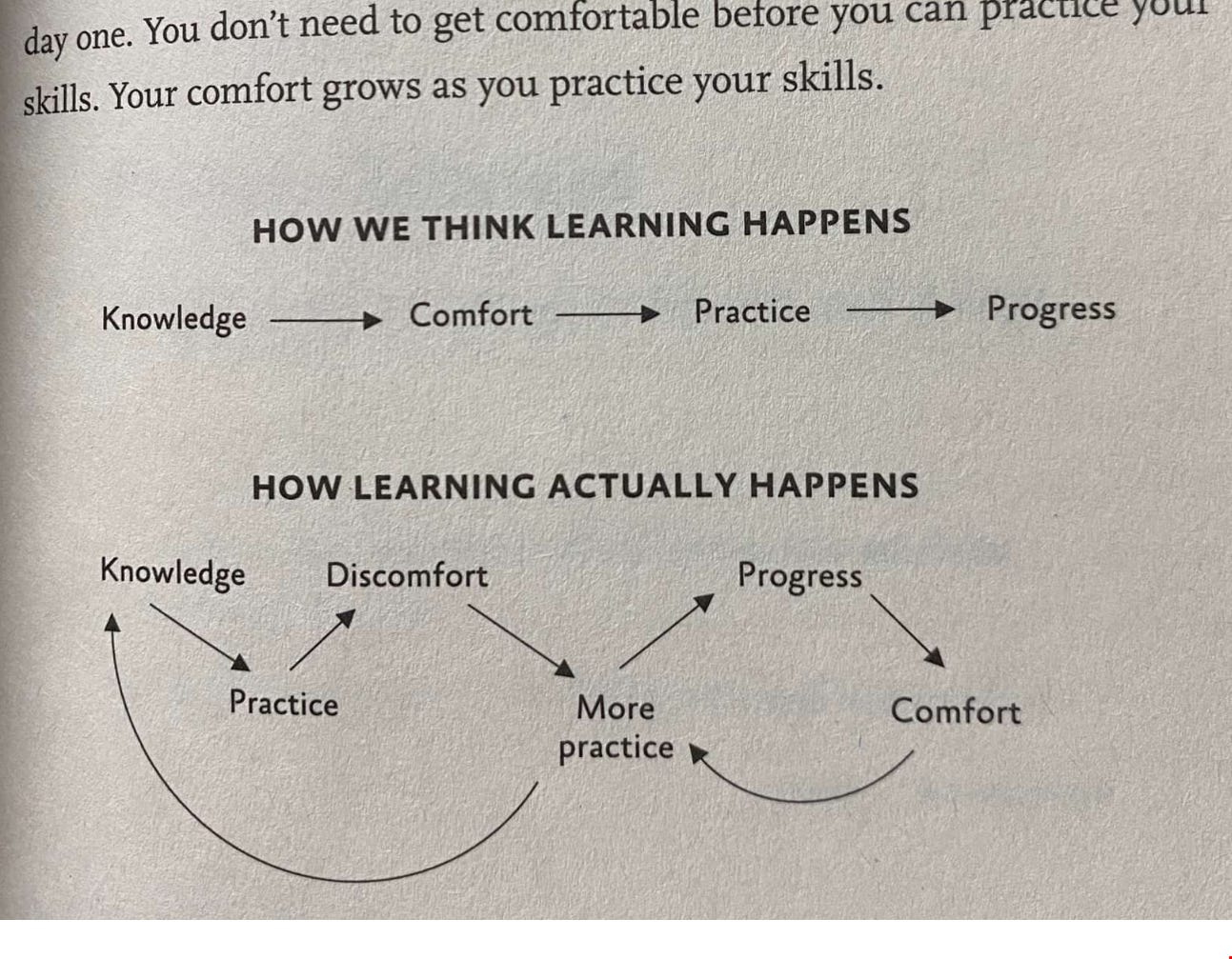

I want my students to know that, as much as I’ve tried to make learning fun this year, sometimes they need to roll up their sleeves, experience some discomfort, and work hard, doing things that are not fun. No one is going to hand them anything. They will need to work hard for it. Success never comes in huge leaps; it takes consistent work. It’s a myth that learning is a straight line from Point A to Point B. Learning is messy. There are going to be falls and times when you want to give up. Adam Grant, author of Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things describes how your comfort in learning grows as you practice various skills. We may think that learning happens in a linear way from knowledge to progress, but in fact, learning is circuitous.

Learning requires discomfort and discomfort for long periods of time is not fun, especially for students so accustomed to the addictive quick rewards of online gaming and social media. Students (and adults too!) want to accelerate their learning by lessening their discomfort. The truth is that there are no shortcuts in learning. We all want to be able to plug into the Matrix and quickly download new skills and knowledge. But I believe that there is more value it working hard and never giving up.

“Nothing in the world is worth having or worth doing unless it means effort, pain, difficulty… I have never in my life envied a human being who led an easy life. I have envied a great many people who led difficult lives and led them well.”

Theodore Roosevelt

I believe that effort beats talent every single day. I tell my students that if they work hard every day, they will be successful in middle school, and in life. Am I wrong in telling them to work hard on standardized tests? It feels dishonest because even though I want them to have experience doing difficult things, I don’t fully believe that getting better at taking standardized tests is vital to life success. I realize that many colleges still require SAT and ACT scores, and many graduate level programs still require the GRE. And yet, I didn’t score well on my SATs and I still went to the University of Colorado, Boulder, an R1 State University. I avoided taking the GRE and was able to earn both a masters and doctorate. I had to work hard in each of those programs, and I don’t think learning how to take a standardized test helped me at all.

Wharton School professor, Adam Grant, says,

When you encounter a result that challenges your lived experience and your conviction, you have two options: one is to say that can't be true and then fall into a trap of confirmation bias and desirability bias. The other is to say, ‘I wonder if my experience might be leading me astray? I wonder if I've formed the wrong conclusion?’

I know that I shouldn’t generalize based on what I see in my classroom. It is possible that my lived experience as a classroom teacher these last 22 years has led me to form an incorrect conclusion. Are there benefits to standardized testing that I don’t know? I’m curious what you think and what you see with your own children and students.

Have a great week.. even if you are standardized testing!

— Adrian

Resources

Just Whose Idea Was All This Testing?

From Socrates to NCLB to Diane Ravitch and The National Assessment of Educational Progress, this is a good summary of the history of standardized testing.

While this interview is long (1:20), I found it very informative. Michael Strong is the founder of The Socratic Experience, a virtual school that equips students through Socratic dialogue. His book, The Habit of Thought: From Socratic Seminars to Socratic Practice, is a bit dated (1997), but I find it very applicable to teaching and learning today.

The Window of Tolerance: How to Better Handle Stress

Having this graphic of the Window of Tolerance has help me better understand how my students respond to stress. This article from Neurodivergent Insights offers a clear explanation of stress and how best to handle the different types.

How to Counter Learned Helplessness | edutopia

I’ve seen in increase in learned helplessness among my students. edutopia is always a great place to help me better understand something I am seeing in my classroom, and to get tools for how to help my students. I recommend you read this article in tandem with Tips for Teaching Realistic Optimism.

I’ve just started reading this book, and I’m already seeing parallels to my own fifth-grade students. I particularly like the four modes of learning that students use to navigate through the shifting academic demands and social dynamics of school: RESISTER, PASSENGER, ACHIEVER, and EXPLORER.

Brené Brown and Barrett Guillen on Living Into Our Values

This podcast with Barrett Guillen is fantastic! In it, they walk through a values exercise that I use with students and my own children.

This quick clip of the Lives Well Lived podcast, Adam Grant explains what he learned when reading a meta-analysis on student attention. Here is the link to the entire episode. It’s worth a listen!

There are so many resources for both teachers and students on this site. They have a great teacher training program that helped me better understand dyslexia. You can even enroll in their University of Dyslexic Thinking.

I heard this line from Denis Morton, a Peloton instructor. I liked it so much that I stole it and have been using is whenever I make my students do something they don’t want to do.

I hate using this word, but he sees his dyslexia as an intellectual disability instead of as a superpower. He’s 16 and when emotions run high, he uses this slur to describe himself.

I think this is related to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow Theory. He states that students are happiest (and learning the most) when “they are in a state of flow — a state of concentration or complete absorption with the activity at hand and the situation.” When you enter a flow state, you are so absorbed that nothing else seems to matter. The challenge of what you are trying to learn is at the same level as your skill or current understanding of the topic you are learning about. You are not bored, disinterested, or anxious. You are in a state of heightened and continuous learning.

1. This most likely is my favorite thing you've written, as it is infused with your own generosity and willingness to live in the margin between strong convictions. What a gift this piece is for any educator or parent (or both) to encounter.

2. It also is incredibly relatable for many teachers, I imagine, who have to "amplify the stakes" in our rhetoric about testing in the classroom despite knowing that, for students, the stakes are often quite low, if not harmfully so.

3. That this is an annual thing, too, a pedagogical, existential crisis that you can block off on the calendar annually? That feels dystopian. (But also so accurate.)

Thank you for this sharing, particularly at this moment in the year, and particularly the pairing of your teacher/parent perspectives.

This is an excellent piece. As an educator and a researcher, I find standardized testing to be a horrible but necessary evil. What I hate about it are all the things that schools and administrators generally prioritize-that it is used for funding, for teacher compensation, and that it tells us something real.

I wish we could instead use standardized testing in the following two ways:

1-To see the rate of growth for a student from one year to the next.

2-To understand the overall proficiency of a cohort group within a school.

To make these two things happen we need to radically reframe how, why, and in what way we think about standardized testing.

First, it should be a lot shorter. Taking time out of the classroom for a week of assessment is actually limiting student growth. I think yearly assessment makes sense but limit the amount of time students are allowed to test. If a school day is 6.5 hours, make it so that no more than 1/2 of a school day of time can be used for end of year assessment a year. This would mean most students would have no more than 2.5~3.5 hours over the course of 5 days. By limiting the time allowed for assessment, you show both students and parents, these are tests to understand what you know, but the priority remains learning-through the last day of school.

A second thing that needs to happen, start tracking individual student growth, year-on-year. It is more important than seeing if a student is ahead or behind at their expected level. Instead, if we showed students and parents what they demonstrated/accomplished over the year in tangible terms, I think less parents would be frustrated by the process. I have seen this work especially well for students with learning disabilities. If you can say, "Look this year you were able to master this skill, that you struggled with last year," it creates motivation to continue and a desire to participate in assessments in the future. Right now, students and parents do not have that, they are a lesson in futility because they do not provide any meaningful information or use. Just as you show in your diagrams, learning is not linear, but we assess it like it is. Adopting this as a practice in standardized testing and requiring the testing providers (that we pay millions of dollars for assessments) to articulate this in clear ways for parents will allow individuals to understand the variability of learning.

Third, with respect to cohort groups, this gets into the weeds with more customized educational pathways in combination with data. If you have a class that is only 20-30% proficient in a particular discipline or topic, that should drive class and cohort placement, instruction, and, if necessary, retention. But, and I want to stress this, it is not about individual students, it is about cohort groups; classrooms, subjects, etc... If an entire class of 7th grade math students really struggled with pre-algebra concepts, that information should be used for planning. The reason this makes a difference is it does not negate the growth a student may have shown. If a cohort is not doing well, and they are just pushed along, both the parents and students become disengaged from the system. It creates apathy towards the learning and instructional process. This is one way school is not like the workforce. If you fail an electrical certification exam, you do not just get to be an electrician-you have to retrain or complete additional coursework. We need to treat assessment in schools using the same standards. When parents understand that these tests are not important for teachers, but for their children and for the collective planning of the school, independent of school finances, then they will also be less likely to allow their children to opt-out.

I know this sounds like a lot, but when I was still in the K12 classroom, this is something I did, including creating custom visualizations (again-should be provided by test makers) to show what students had to learn between assessments. It is also a practice I championed when I took over as a testing coordinator. This allowed for more robust conversations with parents about why we do this thing once a year. Funding might be what makes testing a necessary evil for adults, but if we do not use it and take action on it then testing is unnecessary for students and families. Perhaps by changing the purpose and product of testing we can get students and parents back on board.