Reality Bites

Are we really preparing students for the real world?

I’ve watched Reality Bites roughly 1374 times, most recently with my ever-growing teenagers. My oldest graduated from high school in May and is set for the Marine Corps in July. Since he is not going to college, I thought it would be fun to watch, as a family, the post-college messy attempts of my favorite GenXers: Lelaina, Troy, Vickie, and Sammy. Reality Bites is a 90s time capsule, filled with relics from my childhood: chain-smoking parents, landlines and answering machines, flannel shirts, oversized tees from The Gap, Snickers from the Newsstand, and Lelaina’s VHS camcorder.

As an Elder Millennial, watching Reality Bites in high school, I could never fully relate to the anxiety of life after college. I didn’t have roommates and was still living under my parents’ roof. I wasn’t trying to “make it” in the world; just trying to survive high school. Still, it has always been comforting watching the flounderings of each character. Perhaps we are all hardwired to reject our parents’ generation: Lelaina trashing her parents for trading in their 60s ideals for a BMW; Millennials repudiating our boomer parents for their authoritarian parenting, laissez faire attitudes, and prejudicial societal views. At some point every child questions their parents’ decisions (possibly seeing them as sellouts) and fights for their independence.

These swells of independence begin as early as adolescence and continue to grow through graduation. Whether a child decides to go to (and graduate from) college, we all think we know more than the previous generation. And yet, we rely on our schooling to prepare us for the real world. What does that mean? Did it mean something different in 1995 versus 2025? We want our kids to leave high school with the ability to land a steady job like Lelaina’s dad, or be a cool executive, like Michael Grates (played by Ben Stiller). The last thing we want is for our students to end up like Troy, a college dropout with a 180 IQ “eat[ing] and couch[ing] and fondl[ing] the remote control.” Even if the only thing she learned in college was her social security number, at least Vickie (Janeane Garofalo) is earning a consistent paycheck at The Gap.

At 17, I thought Troy was cool. I loved his band’s name, Hey, That’s My Bike, and applauded his rejection of “the man.” In my 30s, he came off as an arrogant douche, reading philosophy books and quoting Shakespeare. At 45, I feel sorry for him because I feel like public education failed to help him find his creative place in the world.

Hello, you’ve reached the winter of our discontent.

I’m sure that Lelaina, Troy, Vickie, and Sammy would be doing fine thirty years post graduation. ChatGPT informs me that Lelaina would likely “be a successful, albeit perhaps cynical, independent filmmaker, grappling with the challenges of maintaining creative control in a corporatized media environment while still trying to tell authentic stories.” Troy might have achieved some indie fame with his band, having a cult following, and “teaching music at a community college while still wrestling with his intellectual angst.” Sammy would be in a “stable, fulfilling creative career, like graphic design or animation” and Vickie would likely have “carved out a successful career in the fashion industry as a stylist or brand manager.” Even though Michael never broke into the inner circle of friends, ChatGPT thinks he “would have thrived in the digital age, as a top executive at a major media company.” These machine answers do not satisfy my human conscience. As a teacher, I want to know how our public education system can make reality not bite so much for all students.

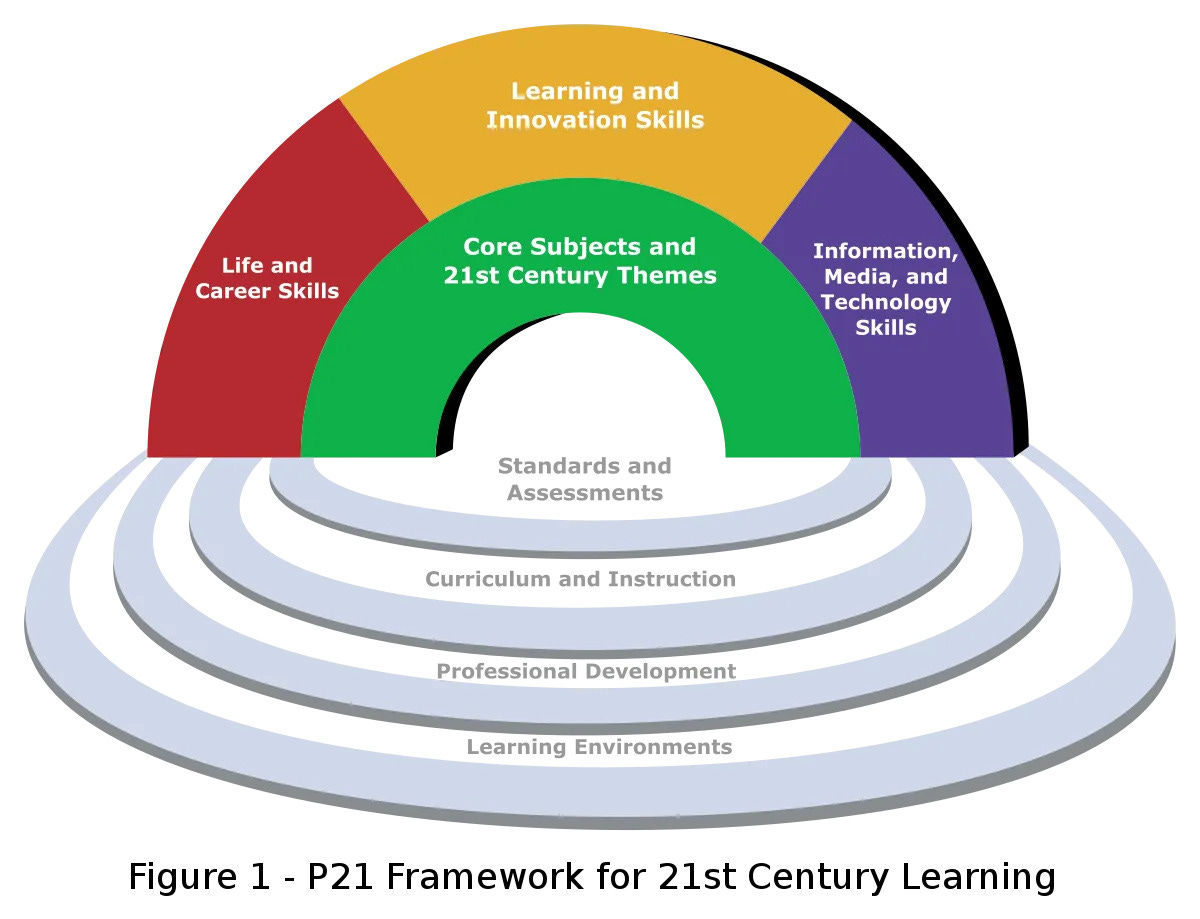

In the early 2000s, preparing my students for the “real world” meant using the P21 Framework for 21st Century Learning, teaching my students the skills, knowledge and expertise to succeed in 21st century work and life. All of my professional development focused on teaching critical thinking, problem solving, communication and collaboration using the new technologies that were quickly emerging. I was told to use P21 Framework with fidelity and highly encouraged to use technology to teach my students how to critically think, problem solve, communicate and collaborate. In order to “navigate complex life and work environments in a globally competitive information age” I needed to teach my students how to be flexible and adaptable; self-directed and have initiative; productive and accountable, producing results. I learned how to integrate 3D printers and robotics kits in my classroom while making sure my students could navigate the internet (and various online, edtech apps) with ease.

Did I prepare my students for the 21st century? It’s hard to say. 25 years later, I find that I’m desperately trying to regain my students’ focus. Multiple generations have now grown up with ubiquitous technology, which, instead of promising enhanced critical thinking, problem solving, communication, and collaboration, has eroded attention spans. I often wonder if I had resisted adopting 1:1 devices in my classroom, gamified apps, learning management systems, and all things Google, how would my students fare today? MOOCs, SMARTboards, and flipped classrooms didn’t revolutionize public education. Instead of thinking critically, I plugged in my students, and let the continuous dopamine drip wash over their brains. And it’s only gotten worse.

In 2010, when the iPad was introduced, it was all about the app. Apps made everything more accessible. You could just click and be instantly connected to a website, game or video. Before the 2000s, how did you learn new skills or improve your existing ones? You probably invested in formal or informal education. You may have signed up for a class or workshop, read a book or listened to a neighbor in your driveway or guest speaker in your staff meeting. In the classroom, teachers relied on textbooks, articles, and books from the library to supplement their instruction.

After the iPhone, content quickly became digitized and accessible online. Learning was now connected to a specific website, app or product. For example, if I want to learn a new language, I would download DuoLingo. If I want to improve my grade in Pre-Algebra, I would visit Khan Academy and take a few lessons. As a teacher I created digital flashcards on Brainscape and review games on Kahoot! I was known as the “technology teacher” who was having students do incredible things online.

Today, the infinity pool of streaming and the barrage of online notifications pull students’ attention in so many different directions. This leads to shortened student attention spans, impatience and irritability with not knowing something, and not seeing the purpose in corroborating facts found online; they record the answer and move onto the next task. Students are unable to think critically about information they find online, and for many of my students, are unable to sit in cognitive dissonance. In trying to prepare students for the “real world”, I inadvertently used technology to depersonalize learning. I encouraged skimming and clicking and created flashy academic transactions to prepare my students for the “real world.”

What made Lelaina, Troy, Vickie, and Sammy unprepared for life after college had little to do with technology. Sure, Michael had his oversized cell phone, but my favorite GenXers left college feeling cynical and disillusioned. In 1994, this had more to do with rejecting materialistic, corporate culture, and 80-hour work weeks. A fifth-grader I taught in 2005 would be 30 years old today. As a member of Gen Z1, despite having higher high school graduation rates and lower dropout rates than those who came before, they are facing the highest unemployment rate the United States has seen in decades. They are graduating from college and feeling unprepared for the real world. Even with the post-pandemic demand for workers, there is fierce competition for jobs, many of which are being replaced by AI. So, it’s not hard to imagine a young adult in 2025 feeling the same way Lelaina did in 1994; it can still take years to find a steady job and a stable place to live. Instead of admonishing the previous generation, Gen Z is worried about today’s political climate and mass shootings in addition to personal debt and housing instability. Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.2

My inner philosopher wonders, Is it possible to ever feel prepared for the real world? Seneca would argue that since so many things in life are outside of our control, one must cultivate mental fortitude and resilience to deal with uncertainty and adversity. Since we all, at some point in our lives, experience anxieties of identity crisis, disillusionment, and a search for authenticity, fortitude seems like a good skill to learn. Fortitude is a cardinal virtue, but can one teach resilience in school? Christopher Perrin, publisher, educator, and Founder of Classical Academic Press, believes you can through consistent love and explicit modeling.

Socrates believed in the importance of developing a virtuous character through seeking wisdom and contemplating the nature of life and death. Plato, a student of Socrates, emphasized the importance of intellectual training and harmonizing the different parts of one’s soul. I agree with prioritizing character over content, but how can teachers foster virtue so that students are prepared to thrive in the real world?

Be more human

One might construe my express concern about an overreliance on edtech as a Luddite reaction; a polemic against all-things digital. It is true that teaching critical thinking, problem solving, communication, and collaboration using technology these last 20 years has disillusioned me to silver-bullet answers that promise to innovate and improve public education. Teachers were trained to treat the P21 Framework skills as widgets that, once manufactured, would enable students to be successful, and in doing so, missed opportunities to help our students be more human. Focusing on students’ humanity over their academic abilities is a profound, yet necessary shift.

Bertrand Russell, believed a “good life” must be guided by love and wisdom.

The good life is one inspired by love and guided by knowledge. Neither love without knowledge, nor knowledge without love can produce a good life.3

He goes on, elaborating that love is the more important of the two.

Although both love and knowledge are necessary, love is in a sense more fundamental, since it will lead intelligent people to seek knowledge, in order to find out how to benefit those whom they love. But if people are not intelligent, they will be content to believe what they have been told, and may do harm in spite of the most genuine benevolence.4

The more public education has relied on dehumanizing technology and boxed curricula to standardize learning, the less human our classrooms have become. Unfortunately, public education is a system designed for knowledge sans benevolence. Sitting for hours in front of screens while bright colors and bouncing characters hold students’ attention does not prepare students for the real world; it prepare students to be on their screens in the real world. Skimming excerpts from online articles, locating main ideas and supporting details, makes students more susceptible to clickbait headlines, and less likely to read laterally in order to fact-check claims. Now, generative AI threatens to completely remove teachers from the classroom. While I’m not immediately concerned with my machine replacement, I am cognizant that I must make a radical shift toward humanity if I am to prepare students for the “real world”, not just a job. Educational reformer and philosopher, John Dewey, viewed schooling as a tool to give students meaning in their lives. If we are to prepare our students to live well in a democratic society, we must view access to knowledge as sacrosanct.

Knowledge is humanistic in quality not because it is about human products in the past, but because of what it does in liberating human intelligence and human sympathy. Any subject matter which accomplishes this result is humane, and any subject matter which does not accomplish it is not even educational.5

While an outright technology ban may seem appealing, I choose to teach to my students’ humanity, not their addictions. Depending on what you read, young adults are either suffering from one of the largest mental health crises in history because of our collective addiction to phones and social media, or teenagers, “have always inhabited worlds that seem foreign and foreboding to their parents” only now, it is online. I’m likely to moderate my reaction, as well as my own phone use, in response to calls to “free the Anxious Generation.” As a teacher, I can only control what happens in my classroom. I can design learning experiences that limit screen time, but once the bell rings, my influence disappears. In fact, I’ve noticed fewer parents placing restrictions on their students’ phone and internet or gaming use. Many of my students, especially boys, have unfettered access to all things online. Not only is this worrisome, it drastically affects my ability to teach and my students’ ability to learn.

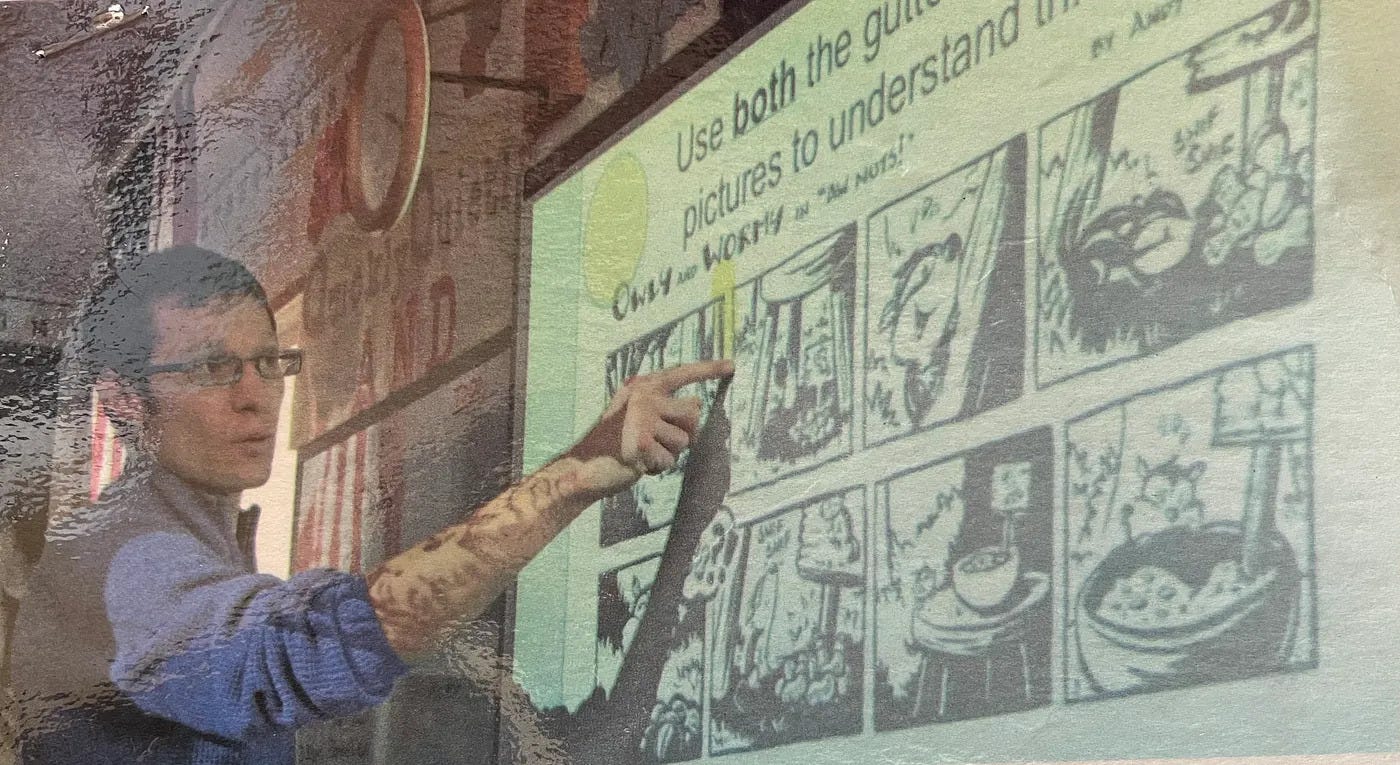

Giving students multiple opportunities to be more human in my classroom will best prepare them for the real world, and avoid graduating cynical and nihilistic. Even if it is only for a single school year, I want my students reading whole novels, figuring out who they are, and what they believe through meaningful writing experiences and classroom discussions. I want my students to know that when they make mistakes, there will always be opportunities to make amends and learn from their errors. Yes, I am tasked with teaching my state’s academic standards for the fifth-grade, but most importantly, I center human virtues such as cooperation, perseverance, honesty, kindness, patience, helpfulness, humility, and compassion. While 21st century skills may sound sexier and more relevant in the Age of AI, I believe human values are what my students need. By putting character building ahead of academic learning, I think my students have a better chance of being successful in the real world. Those ideals that lead to being a better human aren’t ones so easily dismissed by future generations. If I have taught my fifth-graders to be helpful and kind, when they are 23 and searching for themselves, I don’t picture them railing against their schooling.

How can we repair all the damage we inherited?

Lelaina Pierce

Imagine Lelaina’s valedictorian speech if she had been a product of 17 years of learning experiences where her humanity was valued more than her grades. Instead of Troy dropping out of college, moving in with Lelaina and Vickie, and being a master of time suckage, he might have felt a human drive to make the world a better place.

I am not under any orders to make the world a better place.

Troy Dyer

In 1994, the “real world” was whatever was happening on MTV’s The Real World. In 2025, the “real world” consists of mass protests against an authoritarian government, widespread trade tariffs that may or may not violate trade laws and will most likely exacerbate inflation and impact consumer spending, and huge reductions in funding for federal healthcare and education programs. Yes, we still have Love is Blind, Naked and Afraid, and The Real Housewives franchise, but the novelty of Reality TV has worn off. We are seeing what happens in the “real world” when we treat critical thinking, problem solving, communication, and collaboration as more valuable than being human. A public education system that allows its teachers and students to be unapologetically human would have helped Sammy feel more secure in his sexuality. Lelaina doesn’t want her documentary footage to be used for In Your Face, and Troy certainly doesn’t want to participate in a world where fakeness is marketed as authenticity. Life is messy and hard and can't be resolved at “the end of the half-hour… like on The Brady Bunch because Mr. Brady died of A.I.D.S. Troy tells Lelaina that things don’t work out like that.” All that matters is to be ourselves.

I can't really start my life… without being honest about who I am and… I want to be in there, too. I want to feel miserable and happy and all of that.

Sammy Gray

Maybe instead placing the enormous responsibility of solving all of society’s problems on public education, and then attacking teachers for not preparing students for the “real world”, we might recognize that we have a collective duty to make the world a better place by nurturing each other’s humanity. Each of us plays a part in ensuring that subsequent generations enter their world honest about who they are and with enough agency to act intentionally and adaptively towards their goals. The “real world” is a participative synergy between the individual and the collective. Society is a contract. We collectively agree on common rules, ideals, and practices to promote the flourishing of humanity.

No one should have to choose between their integrity, paying the bills, and making the world a better place. Boxed curricula, standardized lessons, and ChatGPT will not prepare students for the “real world.” Scoring high on standardized tests, and then cashing that in for a mountain of college student loan debt, is not going to empower students to make the world a better place. Teachers and students shouldn’t have to check their humanity at the classroom door. The world may not owe us any favors, but we have a responsibility to preserve a virtuous humanity where everyone stands proudly in their own skin, and treats each other with human dignity and respect.

Rewatching Reality Bites more than 30 years later, I worry that we are moving away from the public education system that we actually want for our children. We can’t let our students leave our classrooms feeling less than, disenfranchised, and marginalized. Teaching and learning are inherently human endeavors, and we must fight to preserve them as such. If we want our students to thrive in the “real world”, let’s help them love learning and each other. Let’s teach them how to grow themselves and make the world a better place. Let’s be more human so that reality bites a bit less.

But guess what. I'm a human being, OK?

We're human beings, people, OK?

We're not, like, intelligence quotations or whatever.

Have a great week!

— Adrian

Resources

Author, Robert Greene, has a podcast on YouTube where he discusses a variety of topics. Here, Greene shares what he feels are the most important skills for today’s world. I agree!

‘Reality Bites’ Is Thirty Years Old. Is It Dated, or More Relevant Than Ever?

There are a lot of think pieces online about the relevancy of Reality Bites. This one, written last year by Dan Solomon is my favorite.

Reality Bites (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) - 30th Anniversary Edition

I’m drooling over this 30th Anniversary, double black vinyl edition.

Majority of Gen Z Consider College Education Important | Gallup

This is hopeful article includes 2023 survey data from Gen Z college students. If college is still valued as an important commodity, I wonder how society can make it financially attainable for youth today.

Are High Schools Preparing Students for the Real World? | XQ Institute

This website as excellent graphics, illustrating high school Gen Z seniors who graduated in 2023. The implications are that students today want more opportunities for self-directed learning, in order to learn life skills like organization, problem-solving, and critical thinking.

Anne Helen Petersen’s Substack, Culture Study is an excellent newsletter. She writes as a Cultural Studies professor on all things culture. I really enjoyed reading this piece about Millenials aging and what this means for society. I highly recommend all of Peterson’s posts, but especially this one.

For those of you who are interested in exploring the history of Generation X, Andrew Potter’s nevermind Substack is filled with interesting pieces. From articles about life pre-internet to the dangers of nostalgia, Potter does a wonderful job providing history, analysis, criticism of all things Gen X. He even has a short article about Gen X, Reality Bites, and the fear of selling out.

This incredible interview with Simon Sinek and Dr. Gervais from Finding Mastery is almost 90 minutes, but well worth the listen. If you don’t have time for the entire conversation, I recommend The Value of Investing in Human Skills, Vulnerability and Trust in Building Great Teams, and The Paradox of Being Human.

Or Zoomers or The Zillenials, take your pick.

The more things change, the more they stay the same. Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr in his novel Les Guepes (The Wasps) in 1849.

The article makes you think a lot about growing up and the generational divide. https://elifeonline.io

The article evokes a lot of thoughts about the journey of growing up and the generation gap. This feeling is very similar to when I played https://sprunkiphase-3.com, a game also filled with nostalgia but mixed with the spirit of new discovery.