April can be a tough month for teachers. Standardized testing is either just beginning or wrapping up. For many of us, we still have a few months before the end of the school year. Spring weather tends to be warmer, so the act of sitting in a classroom learning (or teaching) often feels like drudgery.

I finished state testing last week and have five weeks until the last day of school (or 24 days if you’re counting). This school year has been especially challenging. If I’m being honest, these last four years, post pandemic, have been some of the hardest in my 20-year career. If I’m being really honest, I’ve always struggled with classroom management. I favor building strong relationships with my students over abject compliance. Many of my colleagues have sticker charts, passport marks, totaled minutes on the board, marbles in a jar; all in an attempt to cajole or force their students to sit still and listen. My free-flowing classroom, where students are working independently or collaboratively in small groups, can become unwieldy at times. However, I remind myself that my job is not to tame students. My job is to empower and challenge students so that grow into independent and decent human beings.

Behavior management has never been my strength as a teacher. I provide a lot of opportunities for independent accountability, and sometimes, this leads to students being off task or disengaged. I like to think that I’m good at making learning fun and engaging; that my students feel loved and valued. Unfortunately, this school year, I’ve struggled with every aspect of teaching. Even though I don’t seek student compliance, this group of students has been my most defiant, both behaviorally and academically. They have pushed back on almost everything I have asked them to do. I’ve tried lots of different things to help my students be more engaged and present in the classroom, including intention journaling, student reflection, and amplifying the good we see throughout the week. My student have resisted it all.

Recalcitrance

From Late Latin recalcitrantem (nominative recalcitrans), present participle of recalcitrare “to kick back” (of horses), also “be inaccessible,” in Late Latin “to be petulant or disobedient;" from re- "back" (see re-) + Latin calcitrare "to kick," from calx (genitive calcis) "heel" (see calcaneus).

There is this scene in Paul Murray’s book, Skippy Dies, when Howard Fallon, a history teacher who was once a Seabrook student, laments to a colleague about his students’ lack of interest in learning about WWI. Howard is exasperated, and slightly offended, that his students don’t seem to care about anything he teaches, saying, “I don’t know what they care about, frankly. Apart from maybe getting on TV.” Now, replace TV with Minecraft or YouTube, and this is exactly how I have felt this year. What really got my attention, however, was his colleague’s response. I got goosebumps when I read this scene and heard his advice.

The old man swirls the ice in his drink. ‘I wouldn’t write them off just yet, Howard. In my experience, when you can show them something tangible, bring them out of the classroom so to speak, it can have quite an amazing effect. Even a recalcitrant class, they can really surprise you.’

Father Slattery goes on to give some pointed advice.

Well, you have to teach them to care, don’t you? That’s what it’s all about.

I took a deep breath and read that line again. I closed the book, thought about it some more, and then reread the entire passage. I sat with that advice for a few days, not fully knowing what to do about it or how I felt. My job is to teach students, to create a safe and positive learning environment so that they want to learn.

What if my students just don’t care about school? Can I teach them to care? How?

I believe this is the core of why I’ve struggled so much this year. Before the pandemic, I felt that I could always get my students somewhat excited about what we were learning.1 Yes, there have always been aspects of school that are banal and obligatory. Still, I could motivate almost every student. This year, I haven’t been able to motivate my students to learn much of any academic content. Teaching has felt impossible.

David Labaree, author of How to Succeed in School Without Really Learning and Someone Has to Fail: The Zero-Sum Game of Public Schooling attributes, at least part of this academic apathy, to what he calls the “American School Syndrome.” He believes that as a system, public schools “have never really been about learning. The impact of school on society has come more from the form of the school system than from the substance of the school curriculum.” He goes on to say that teachers can create a classroom community and shared social and cultural experiences, but in the end, the content has never really mattered much. What matters is how education promotes democratic equality, social efficiency, and preserves a student’s zone of opportunity. Discussing these appropriately would require a separate post. I’m not convinced that my ten-year-old students are thinking much about social efficiency or how to be a democratic citizen. However, I do wonder if the answer to the question, Why do I need to learn this? has become more irrelevant since the pandemic. Remote learning gave students and parents a peak behind the curtain, and many are convinced that having a love of learning isn’t necessary. Just get through school and get a job and be successful.

My enthusiasm isn’t contagious anymore. Students see me get excited about teaching the American Revolution, or a particular poem, and they choose to ignore me, opt out of the experience, or refuse. My students don’t want any cognitive dissonance. Their attentional presence seems to have atrophied. They only want to chat with their friends and be online. The “I don’t want to” responses have been replaced with “No! I’m not doing that!! You can’t make me!” My students are right; I can’t make them care about school or do anything they refuse to do, but can I teach them to care?

Teaching my Students to Care

I know that my students are caring individuals. I treat them with respect and dignity, and even though they can be disrespectful and disruptive, there have been moments of caring kindness. A couple of weeks ago, my students demonstrated just how caring they are. I had to step out of class to take a phone call about our family pet, Stanley. Unfortunately, he has been suffering from seizures, and in the moment, I thought we were going to need to put him to sleep. My students knew about Stanley’s seizures, but they didn’t know exactly what I was talking to my wife about.

My students showed me a level of caring compassion that took me by surprise. I was overwhelmed with their love and support. This moment brought us closer together as a class, and I am so grateful for it. We spent the afternoon sharing stories about beloved pets. Each time a student teared up, other students stood up to comfort them.

Now, how can I take this level of caring for each other, and apply it to caring about school? Hungarian psychologist, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, states that students are happiest (and learning the most) when “they are in a state of flow — a state of concentration or complete absorption with the activity at hand and the situation.” When you enter a flow state, you are so absorbed that nothing else seems to matter. The challenge of what you are trying to learn is at the same level as your skill or current understanding of the topic you are learning about. You are not bored, disinterested, or anxious. You are in a state of heightened and continuous learning. Teachers can increase the opportunities for flow states in their classrooms by showing students the relevance of what they are learning to their lives.

I have designed many learning experiences this year, but have yet to see my students in flow. What is assumed in Csikszentmihalyi’s description and the above graphic is the willingness to participate in thinking. I have had moments where I’ve engaged my students’ curiosity about a specific phenomenon or challenge, but it hasn’t lasted for more than a few minutes before they disengage and begin to socialize with each other.

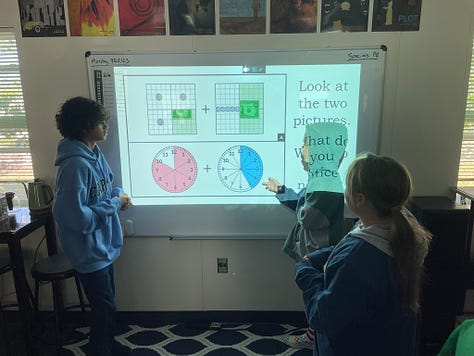

I’ve limited the amount of time I spend giving directions so that I can maximize students’ thinking time. In fact, I’ve restructured my mathematics instruction to be more of what Peter Liljedahl calls a Thinking Classroom, getting my students up on their feet, collaborating, and thinking through challenging problems everyday.

The more I push my students to think, the more push-back I receive. My students’ recalcitrant behavior has made many days feel more like a fight than a collaboration. I’ve tried to connect the curriculum to my students’ lives, but they just aren’t buying it. They just don’t see any relevance to being in school. It is an obligation they hate.

Every colleague I’ve spoken to, attributes this recalcitrance to this particular group of students. It’s like this group of fifth-graders was deemed “difficult” in Kindergarten, and everyone has just suffered through them every year. I get sad whenever I think about this. I’m not sure who is responsible, or even if it is worth examining. I’ve spent time reflecting on my level of ownership to my students’ engagement versus their own accountability. In January, I sent an audio clip to

podcast and they were nice enough to respond thoughtfully to my meditative monologue.It’s not worth trying to find blame as to why my students kick back. I’m more concerned with trying to help my students have a positive school year where they feel safe and valued. Ideally, I want them to learn academic content, but if that hasn’t happened this year, I want my students to at least be curious about learning and work to challenge themselves each day to be better than the day before. I want them to value hard work and see the relevance of being a lifelong learner.

In Japan, there is a specific term for this type of relevance: ikigai. It embodies the idea of happiness in living. In the United States, many understand ikigai as an overlapping intersection of what you love, what you are good at, what the world needs, and what you can be paid for. Ikigai is something deeper, however. It’s the reason people wake up in the morning. Ikigai is composed of two words: iki, which means life and gai, which describes value or worth. According to Akihiro Hasegawa, a clinical psychologist and associate professor at Toyo Eiwa University, the origin of the word ikigai goes back to the Heian period (794 to 1185). “Gai comes from the word kai (“shell” in Japanese, considered highly valuable), and from there ikigai derived as a word that means value in living.” Over time, ikigai evolved to be thought of as a comprehensive concept that incorporates such values in life.

Hasegawa points out that in English, the word life means both lifetime and everyday life. So, ikigai translated as life’s purpose sounds very grand. “But in Japan we have jinsei, which means lifetime and seikatsu, which means everyday life,” says Hasegawa. The concept of ikigai aligns more to seikatsu and, through his research, Hasegawa discovered that Japanese people believe that the sum of everyday small joys results in more a fulfilling life as a whole. I want my students to see learning as a joyful act.

I may not be able to teach my students to care about Geometry or the Revolutionary War as deeply as I do (or at all), but perhaps I can teach my students in these final weeks of fifth-grade about finding their ikigai. I’m currently designing a learning experience where my students reflect on their reason for being. Even if I failed at helping my students grow academically, I want them leaving my classroom with a strong sense of self. I want them to know that learning doesn’t have to be boring. I may not be able to teach them to care about school, but I’m going to spend these last 24 days teaching my students how to care for themselves. I won’t stop trying to get them to care about learning math or becoming a stronger reader. I want them to be independent, not needing me to constantly push them to think and work hard. As David Labaree says, “One of the cool things about being a teacher is you make yourself unnecessary if you do your job well.” I don’t know if I was that great of a teacher this year, but perhaps I can still inspire a love of learning; even if they kick back and fight me every step of the way. They may be cantankerous, but they’re mine.

Let me know what you think!

Have a great week!

—Adrian

Resources

Do Students Care About Learning? A Conversation with Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

A great conversation with one of the great educational psychologists.

As always, John Spencer does a wonderful job explaining Flow Theory.

Creative Schools: The Grassroots Revolution That’s Transforming Education

This book is incredible! It is filled with motivating anecdotes, observations and recommendations that helps me stay positive when I’m feeling down.

Want to see a Thinking Classroom in action? Check out this video.

Ikigai: A Japanese concept to improve work and life

I’ve read a lot about Ikigai, and this article does a great job of simplifying and explaining the concept to Westerners unfamiliar with the idea.

This podcast has helped me process David Labaree’s main premise in his book, Someone Has to Fail.

Students Care More About Education When You Care About Them

Everything in this article affirms my beliefs about teaching and learning. One area I am working on for next year is giving my students more ownership in their learning.

Hearing Daryl Williams Jr. explain these three types of students has helped me reframe my approach with trying to motivate my students. I haven’t read his book yet, but I think it would make for some great summer reading.

Memory is a funny thing. What I remember versus what it was actually like may not match. I’m positive that I’ve had challenging students before and have struggled to motivate everyone. This year just feels harder.

I'm sorry about your dog and hope that he's on the mend - I've been worrying about you since your past post!

Regarding students, I always think about how I'm "planting the seed for future learning" when students push back in the classroom.

Sometimes it takes years for students to appreciate school and their former teachers. As a high school teacher of Seniors, I promise you that it comes. So often kids will talk about how terrible they were in upper elementary and middle school and how much the appreciate (and feel sorry for!) those teachers.

I’m going through the same thing this year. Behavior is the worst I have seen in 21 years of teaching. I’m thinking of a new career. I bought some books to read over the summer about post-Covid teaching and group work, etc. But right now I feel pretty dejected.