Discover more from Adrian’s Newsletter

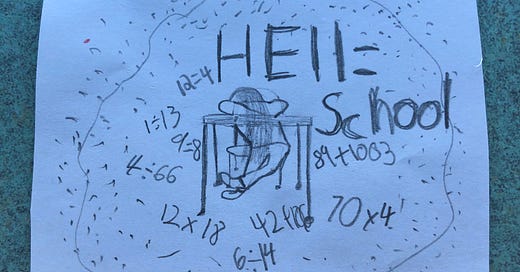

I became an educator because I believe in its power to transform the lives of children. I know that children have the capacity and capabilities to change the world, making it a more just and equitable society for us all. Unfortunately, at a certain point in my teaching career, I began hitting more and more obstacles and experiencing more conflict in my job. I never lost my moral center, but it was increasingly conflicting with how colleagues and administration operated within the public education system.

I didn’t want to burn out. I needed a drastic change.

In 2015, I left the classroom to become an instructional coach. Designing and delivering professional development was a large part of my job. For five years, I tried to create professional learning experiences that helped teachers tap into their expertise and experiences to change the educational system. However, most of our professional development focused on mandated initiatives. Each time I hosted a professional learning session, I was struck by the disconnect between what we were discussing and the actual problems teachers faced in their day-to-day teaching.

Four years into my new job, I met Angie UyHam, founder of the Cambridge Educators Design Lab, at SXSWEDU. During her session, EdLab Remix, she shared her success with using human-centered and community-driven design to address pressing challenges in education. UyHam, along with her colleagues, were creating brand new models of professional learning in their respective school districts. What was most impressive was that UyHam’s Design Lab in Cambridge Public School District was able to successfully change the historically top-down, decision-making approach in professional development. They were able to successfully create opportunities for teachers to invent novel solutions and leverage community partnerships. I was mesmerized with possibilities! UyHam’s passions about the intersection of education, innovation, and social change matched my own. She was able to successfully transform how her public school district identified and addressed systemic problems.

If she could do it in her school district, why couldn’t I do it in my own?

What if we had an experimental lab that helped classroom teachers find solutions to their most stubborn problems (like Google X or Lockheed’s Skunk Works)? This innovation lab would be able to take the pains that teachers feel and the problems teachers see, and reframe them into design challenges for them to solve. What a crazy idea!

I knew that this would definitely face uncertainty. Executing a good idea can be difficult in the best of situations, and I didn’t know how I could pull this off as a instructional coach. I needed to use my classroom teaching experience of engaging and empowering students, combine that with design thinking, and apply it all to the biggest and most pressing problems teachers face in the classroom.

Then, I learned about Jake Knapp’s Design Sprints.

Time to Sprint!

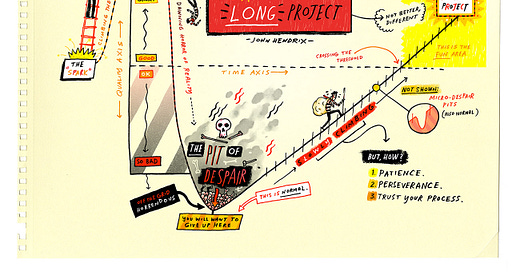

Jake Knapp, author of Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days, is a self-professed process geek. Landing a job at Google allowed him to experiment with everything. He had opportunities to think deeply about how he and his team were efficient and successful with certain projects (Google Hangouts), but struggled to get other projects off the ground. He realized that the key ingredients were individual expertise, time to prototype, and a hard deadline. This formula became the rough blueprint for what he called a Design Sprint. With every new project Jake refined his process, using the format on projects such as Google Chrome, Google Search, and Gmail. He distilled his sprint to an aggressive five-day process that worked for all sorts of websites, marketing strategies, and innovative projects.

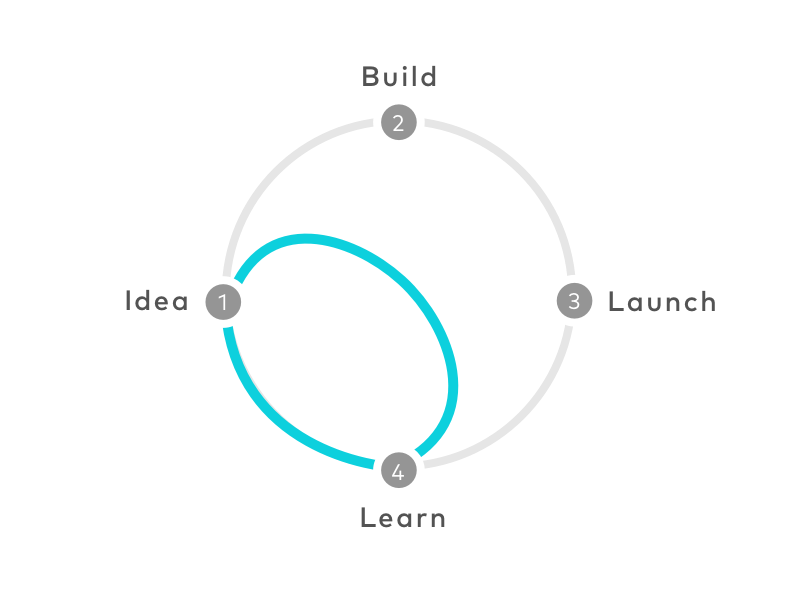

The point of a Design Sprint is to build and test a prototype in just five days. “It’s like fast-forwarding into the future so you can see how customers react before you invest all the time and expense of building a real product.” Design Sprints are not about solving small problems more efficiently, but quickly trying to solve a difficult problem.

The bigger the challenge, the better the sprint.

Jake Knapp

The professional development I was factilating was not innovating my school district. At best, I was helping create pockets of creative teaching instead of widespread system change. I couldn’t think of a bigger problem or a more important project than helping my school district be more innovative and culturally responsive. Redesigning public education, at scale, and creating a culture of anti-racist moonshot pedagogy is an audacious goal. As an instructional coach, I wanted to replicate with teachers the experiences I was creating for my students as a classroom teacher. Instead of facilitating a prescribed training, I wanted to make a real difference in improving the classroom learning experiences for student in our school district.

So, at the beginning of the 2019–2020 school year, inspired by Knapp’s Design Sprint and UyHam’s Design Lab, I co-created the X Lab with my colleague, Jon Pierce. The X Lab was designed to be an idea accelerator for teachers. The X represented the exponential outcomes we hoped for. I believed that if we could adapt a Design Sprint for teachers to solve problems in their classrooms and school buildings, then this educational Research and Development (R&D) Experimental Laboratory experience would have an impact on not only their schools, but our entire school district.

Stubborn and systemic problems in education persist year after year after year. Racial achievement and opportunities gap in public education, as well as equal access to high-quality learning experiences for marginalized students, prevent public education from having a positive impact in the lives of all children. Our current educational system only allows teachers and administrators to try and solve problems by learning separate, standardized, and discrete skills. I wanted to give teachers the opportunity to actively solve their own education problems and implement collaborative solutions in their classrooms. I wanted the X Lab to be a separate place where the things that seem impossible (and sometimes even crazy) in the classroom are field-tested so that teachers are handed a guidebook for doing the impossible.

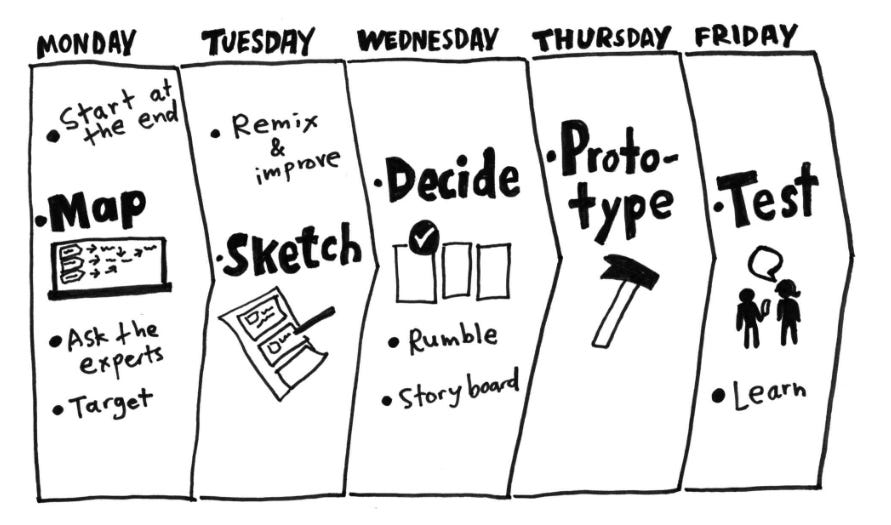

I knew it was going to be tough to have teachers clear out an entire week for professional learning. Would taking five days off from teaching, and making sub plans for an a week really be worth the hassle and effort? Jake Knapp believes in the 5-day sprint. Each day is designed for a single focus: Monday is for mapping out the problem and picking an important place to start. On Tuesday, participants sketch solutions and battle them against other ideas. Wednesday is for synthesizing the first two days and deciding on a testable hypothesis, getting ready to prototype. Thursday is for prototyping. On Friday, participants test out their prototypes with real people.

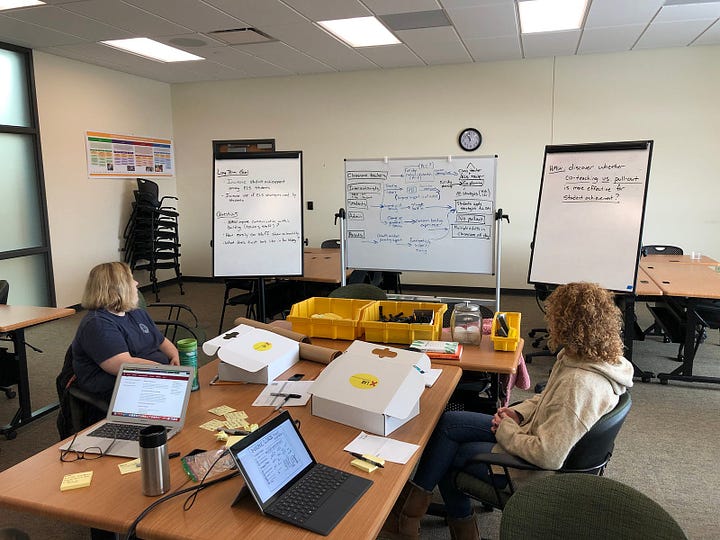

The best advice I received from UyHam was to start small. During her first year, she worked exclusively with 3–5 teachers in her building before scaling larger. I was able to find a few brave volunteers who could be out of their classrooms for professional development for two full days. Compressing the Sprint schedule to two days seemed reasonable if I didn’t forgo the prototyping phase. Maybe I could work with teachers in their buildings to test out their prototyped learning experiences after our two-day intensive? I trusted Knapp’s process and knew that the only way for me to see if Design Sprints could work in my school district was to try. I wanted the X Lab to be completely opt-in and collaborative. I knew that if we dedicated the time, trusted the Sprint process, and focused on our students, then our solutions would have a real impact.

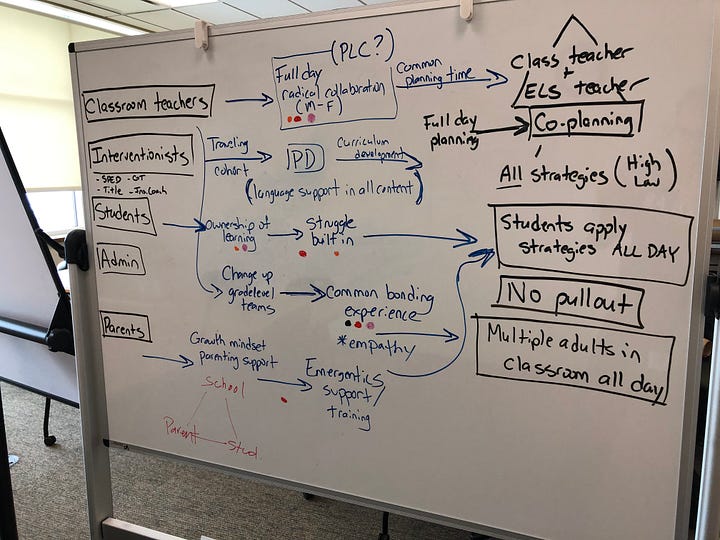

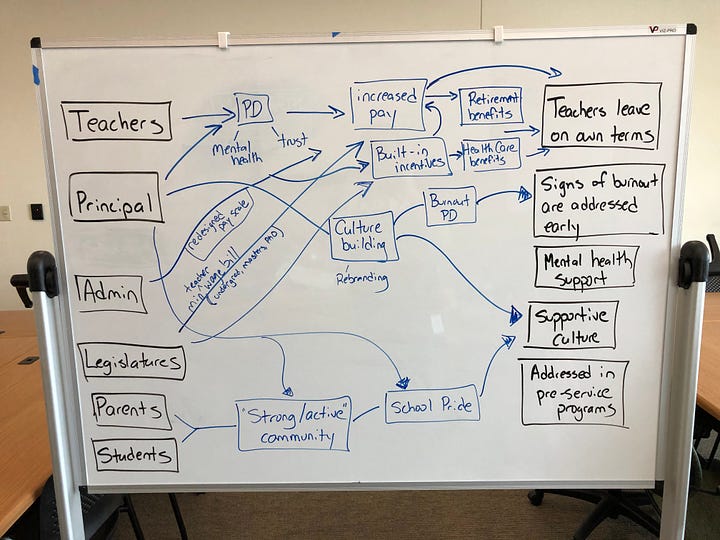

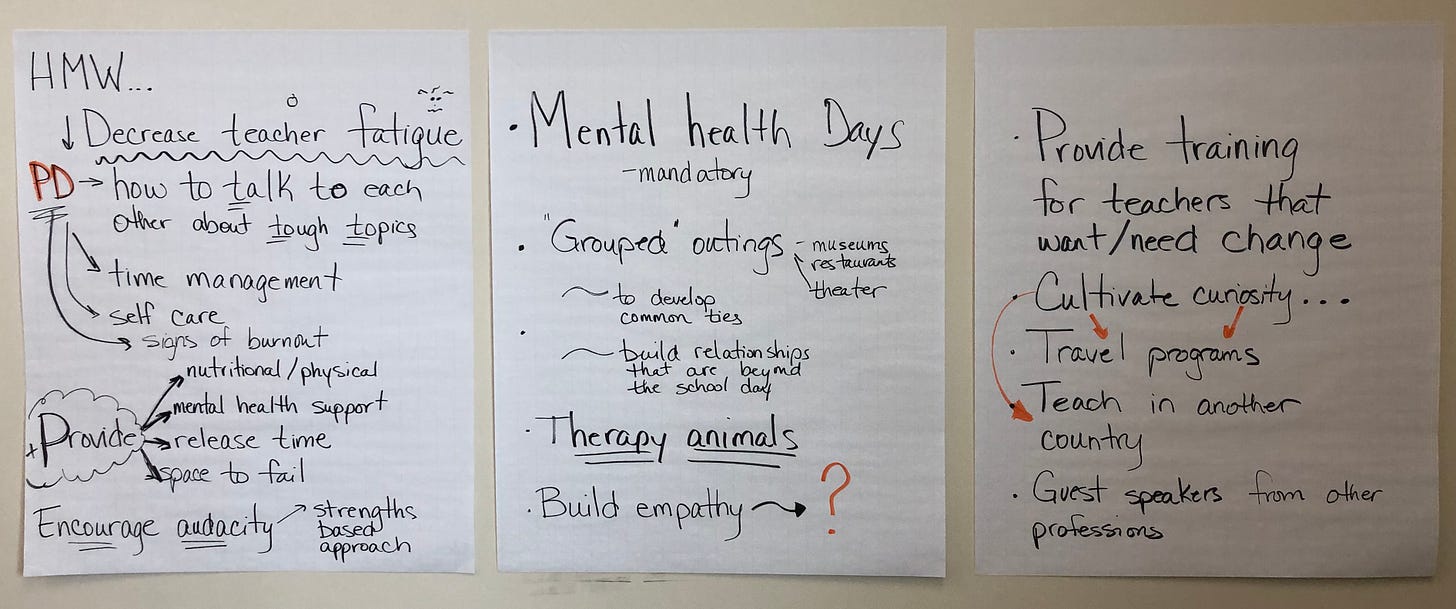

Our goal for the X Lab Pilot was be student-centered, optimistic, radically collaborative, and experimental. We committed to creating learning experience that would be culturally responsive, field-tested with students, rapidly prototyped, and ready to implement in the classroom. Teacher participants spent three days (they were so excited after Day 2, they wanted another day to debrief) exploring questions such as:

How might we increase student achievement among students who use special services?

How might we improve the culture of our building?

How might we decrease the number of teachers leaving the building after five years?\

I learned a lot during that pilot year. By having a truncated schedule, we divided the prototyping process over the course of a semester. This lack of continuity created a slow start once we met again. We didn’t have the same momentum we would have had if we sprinted without interruption. Running parts of the Design Sprint also proved to be difficult as not everyone was as engaged via video conference versus in person. No matter what, I learned that even with the bumps, using student-centered design thinking to run a Design Sprint with teachers was exhilarating. Just putting educators in the same room with the job of creating impactful design solutions for their buildings was amazing to watch. We were able to reframe the way we look at educational problems as a district. The Design Sprint encouraged us to see problems as opportunities and to collectively find solutions together. It promoted partnerships between teachers in different schools and represented a powerful system for local, sustainable, and creative innovation. The teachers who started on Day 1 may have felt the start of burn-out forming, but those same teachers felt invigorated when they left. They reaffirmed with their moral centers that brought them to public education.

Design Sprints with Students

Now that I am back in the classroom, I’ve always wanted to try a Design Sprint with students. This year, a colleague and I are hosting an after-school club we hope will promote student agency in our school building. Voices for Change will have a focus on collaboration and building community, empowering students to identify issues within their school and create actionable change. We want to help students grow their skills to be active, solution-oriented student-leaders in their school building.

What if we used design sprints to help students identify challenges within their school, prototype solutions, and help them bring kindness, justice, and inclusivity to the building?

We are still in the early stages of planning and recruiting students for this learning experience. One resource that we feel will be helpful in teaching students how to be active changemakers in their school is Learning for Justice’s Speak up at School. By teaching students how to Interrupt, Question, Educate, and Echo, we hope to inspire students to create lasting change in their community. Similar to my X Lab pilot experience, I believe that giving students time to map out problems, sketch solutions, decide on a testable hypothesis, prototype, and test out their ideas, Voices for Change could be the student equivalent to the X Lab. I’m excited for the possibilities!

Have a great week!

—Adrian

Resources

Jake is probably the best person to explain a Design Sprint.

How to Run a Design Sprint at your School in 9 Steps

Ariel Raz is an incredible educator at Stanford’s d.school. Check out how he as used Design Sprints in Stanford’s K12 Lab.

Adapting Design Sprints For Education

Another great example of designers using Design Sprints with educators.

Design Sprints for Kids: Unlocking the next generation’s creativity

This is such a great story of how a seven-year-old used a Design Sprint to achieve her Brownies Inventor badge.

Another great story of a family who used a Design Sprint during the Covid quarantine.

This site has a lot of great resources for educators looking to increase student agency through leadership lessons.

A YouTube playlist that shares examples of biased or hateful comments. These are thought-provoking and can help you have a plan in place to help you speak up.

I worked as a learning experience designer before teaching. Design sprints are great!