Hot Mess Soup

Navigating absurdism in public education

If there is one novel that captures the overwhelming ridiculousness of teaching in 2025, it is Catch-22 by Joseph Heller. Written in the eight years after WWII, and finally published in 1961, Heller tells the story of Captain John Yossarian, an Air Force bombardier desperately trying to escape combat and stay alive. Heller, himself, was a bombardier in the U.S. Army Air Corps and flew over 60 combat missions in Italy.

While I make no attempt to compare my experiences as a public school teacher with those of combat veterans in any conflict, I do feel like I am navigating a hot mess soup.

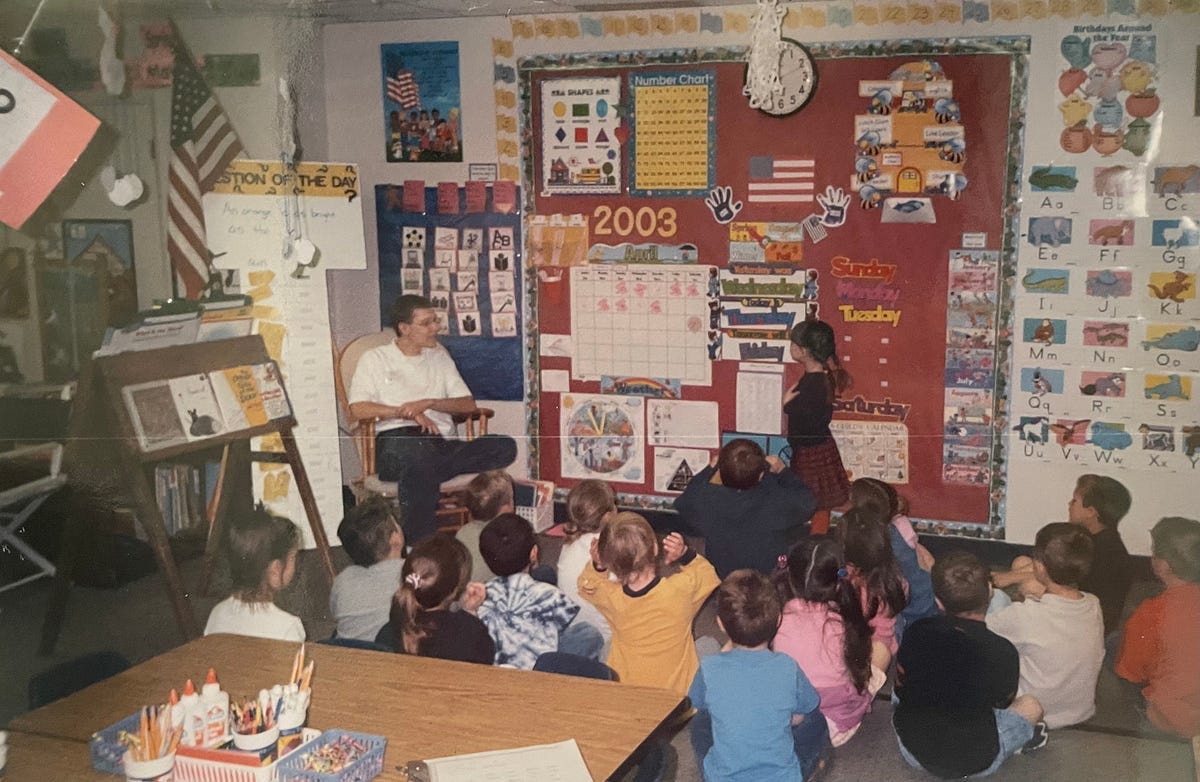

As with gradual chaos, it’s been slowly getting worse for some time. I first sensed that teaching was becoming unmanageable in 2005. I had been teaching for a few (messy) years and was still trying to figure out how to teach. I may have been armed with reams of educational theory from my college courses, and even had some classroom experience as a student teacher, but those first years in my own classroom proved difficult. I arrived bright-eyed with notions of “hands-on learning” and creating a “learner-centered” classroom. I was hit with the stress of being responsible for the academic growth of 30+ students as measured by our state’s newly adopted standardized test. What started as week-long practice sessions to prepare students for the exam, soon became months of teaching to the test and taking practice exams. Once the spring semester started, I was coaching students on what to eat for breakfast on the day of testing in order to score well and passing out mints because we were told they helped students better focus. I covered up instructional posters and reassured crying students that their scores would not negatively impact their lives.

When the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) Initiative arrived in 2010, I was really struggling to do all the things. Not only did I need to prepare my students for the spring standardized test, I was now flipping my classroom, uploading learning content and resources to our district’s Learning Management System (trying to mimic a MOOC), and, even though we were already a decade into the 21st century, trying to teach my students 21st century information, media, and technology skills. The CCSS promised to create “clear, consistent K-12 learning goals in Math and English Language Arts (ELA) to ensure all students graduate ready for college, careers, and life.” CCSS guaranteed a focus on deep understanding, critical thinking, and real-world skills. What it did was homogenize classrooms, fragment learning into testable skills, and discriminate against students living in low socioeconomic areas.1 It was the start of the mess, but I did not recognize it; this was teaching in the 2010s.

Then Steve Jobs released the iPad. Teaching and learning were now about downloading apps. Apps made everything more accessible. You could just click and instantly be connected to a website, game or video. Learning content became synonymous with accessibility to the internet and constant connectivity online. Digitized learning was now connected to a specific website, app or product. For example, if I wanted to learn a new language, I could download DuoLingo. If I wanted to improve my grade in Pre-Algebra, I would visit Khan Academy and watch a few videos. As a teacher I could create digital flashcards on Brainscape and review games on Kahoot! The word, migrating, once used for people and animals, was now used for data. My students started asking Google the answers to their questions instead of me.

Again, I didn’t think much of it. I was swept up in the tsunami of digitized and democratized learning. I was innovating my classroom to give my students an edge. Soon, they received their own device for use in the classroom. Computer labs shrank into computer carts and then shrank again into smartphone hanging pouches.

For ten years, I never thought about the consequences of ubiquitous technology. Slowly (and then quickly) I watched my students’ attentions spans dwindle and their impatience and irritability grow. Over time, they could not sit long in cognitive dissonance and struggled to corroborate online information. They wanted to get an answer and move on to to the next game. Studying one website for a research project became having 30 open tabs; today, students are back to using just one tab: ChatGPT.

During that decade, the hot mess turned into a stew. There were so many things floating around that I had to attend to, and the temperature was rising. As my class size increased, my teacher agency shrank. Early in my career, I felt overwhelmed by the amount of pedagogical freedom I had in my classroom. I was trusted to teach reading, writing, math, science, and social studies using any instructional materials. Being a novice, I leaned on my colleagues and learned about various curricula they were using and having success. This was before Teachers Pay Teachers (TPT), so I trusted my teammates’ expertise. Ever so slowly, mandated initiatives and standardized curricula began to edge out my novel studies and science projects connected to the mathematics concepts students were learning. Our district began piloting various curricula, starting with a new mathematics curriculum. It took five years before every teacher was trained and teaching it with fidelity. In five years, I was overburdened with learning and teaching a new mandated curriculum in every subject area. This was the matter of course before the pandemic hit in the spring of 2020.

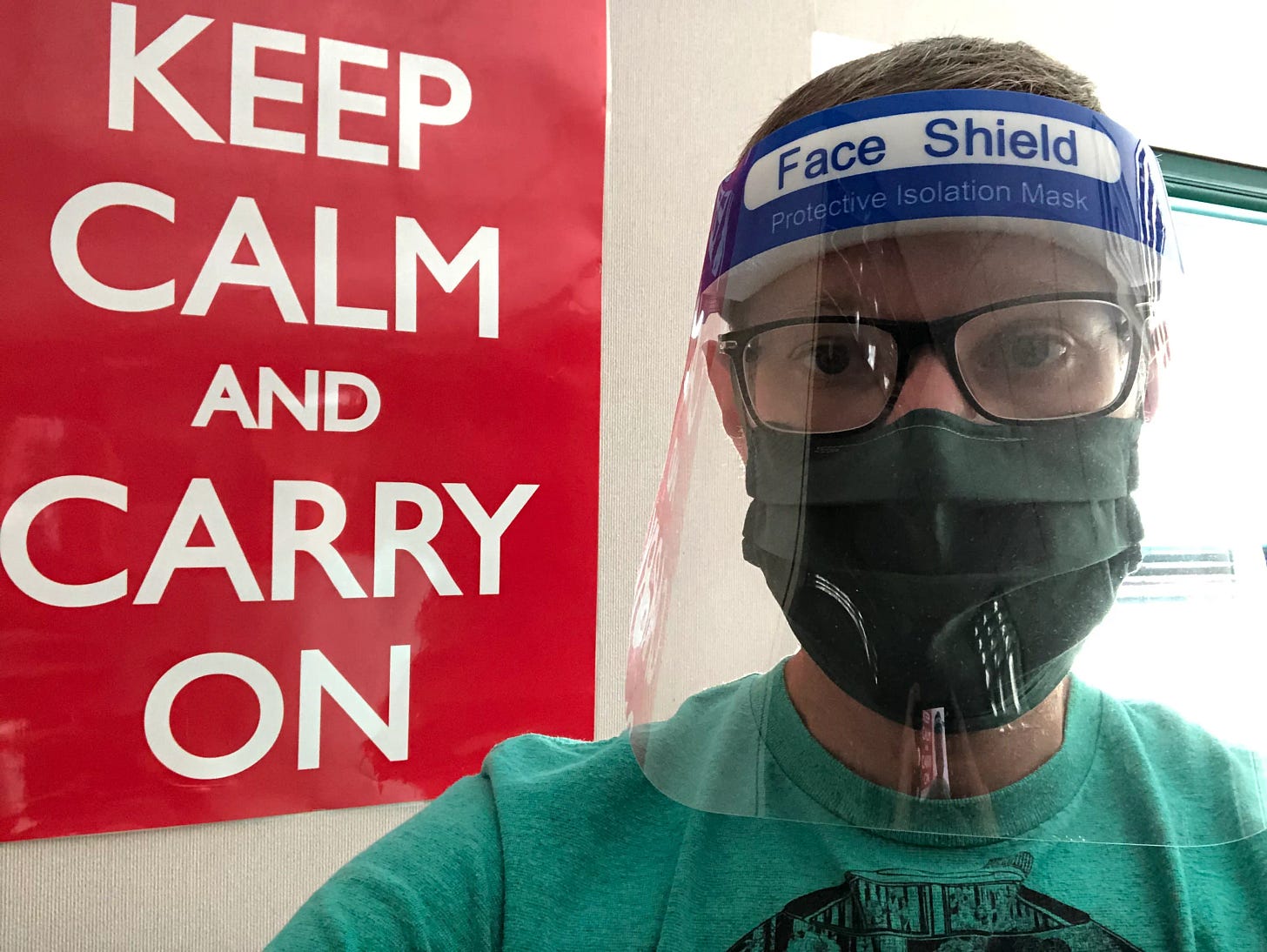

Teaching in a pandemic remains the hardest thing I’ve ever done as a classroom teacher. I felt like a first-year teacher all over again. Everything was difficult. Students were resistant. I was fearful and became a germ obsessive-compulsive, authoritarian teacher. All day I told students to keep physically apart, keep their masks covering their faces, and wash their hands. Learning took a backseat to health and safety. Once we emerged a couple of years later, the term “learning loss” was everywhere. And so, unsurprisingly, the school system tightened, and kept tightening for five more years.

So many things have turned the teaching profession into a hot mess soup. In addition to sweeping initiatives and standardization, school shootings remain a constant fear. When I first became a teacher, there were 20 deaths in the U.S. resulting from school shootings. Today, over 390,000 children have experienced gun violence at school. It has become as ubiquitous to school life as technology. Students are desensitized to this unnatural violence; they commonly practice active-shooter drills and think of them like obligatory fire drills and severe weather warnings.

This is where I find myself, teaching in 2025. After decades of nonsense, it feels impossible to claim any sort of pedagogical expertise among the myriad stressors and anxieties I have experienced in my career. Throughout my quarter century as a classroom teacher, I have encountered all number of overreaching, illogical contradictions. Like Yossarian, I have felt trapped in a sane-insane circle of logic and irrationality. I’ve been told to teach whole novels and give students books to read, and then directed to replace those books with textbooks and give students endless practice finding the main idea of excerpted texts. I’ve been encouraged to give each of my students a school laptop, and then questioned as to why they are skimming and scanning blue screens instead of deep reading. I’ve plugged my students into their devices, and then been lambasted for not being able to keep my students engaged after I disconnect them. Such is the Catch-22 of public education: schools lack basic instructional resources, and teachers are criticized for not doing enough to educate students. I feel caught between the impossible demands of following a standardized reading curriculum that kills any joy of reading, while trying to convince my students that books are magical. How can I support my students who need extra time learning or differentiated instruction when every minute of my regimented day is spent pushing them through the curriculum pacing guide?

Of course they’re crazy … you can’t let crazy people decide whether you’re crazy or not.

Doc Daneeka, Catch-22

This year, especially, feels particularly impossible and absurd. Every time I feel like I might settle into a routine in my classroom, the rules of engagement change and I’m expected to do more with less and less. This is the central paradox Yossarian feels. Colonel Cathcart constantly increases the number of dangerous combat missions required for soldiers to go home, preventing anyone from actually going home. As soon as my students and I get through one 15-Day Challenge, I learn there are more required. Sometimes I feel like I’m screaming into the void of The Twilight Zone while everyone around me maintains their Stepford-wife compliance and conformity.

Navigating the Absurd

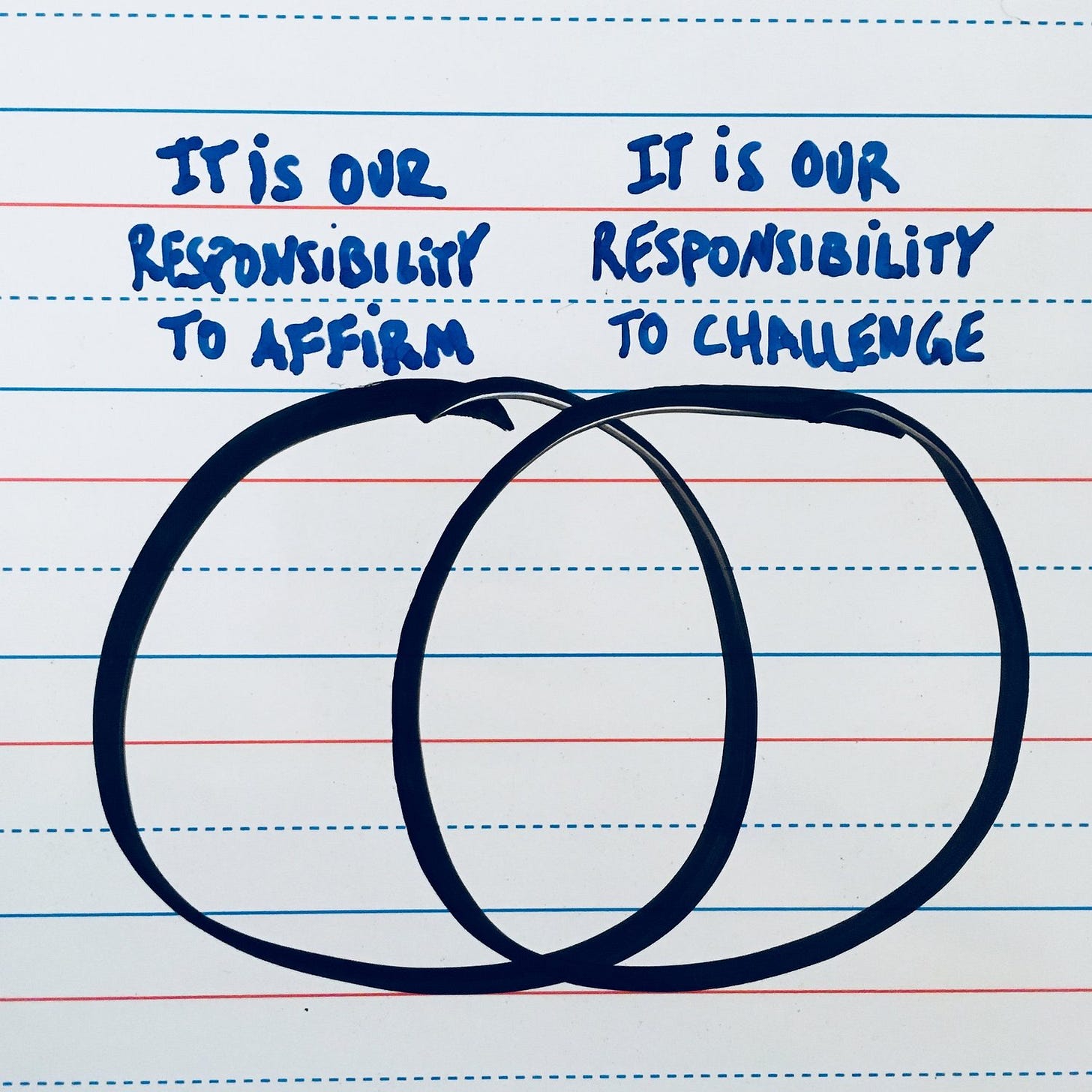

Teaching is filled with absurd paradoxes. In Alex Shevrin Venet’s book, Becoming an Everyday Changemaker, she discusses embracing absurd contradictions in public education. She uses Vent Diagrams to help people navigate such incongruities. Venet explains that to create a Vent Diagram, one writes two contradictory truths, leaves the center unlabeled, and considers how one might “move from the overlap.”

The creators of Vent Diagrams explain how this activity helps break binary thinking.

Venting is an emotional release, an outlet for our anger, frustration, despair -- and as a vent enables stale, suffocating air to flow out, it allows new fresh air to cycle in and through. We’re trying to make ‘vents’ in both senses of the word: tiny windows for building unity and power, emotional releases of stale binary thinking in order to open up a trickle of fresh ideas and air.

Teaching has always been a both/and. Teaching is both an inspiring profession and a challenging career. Teaching is both a calling and a job. Teaching is both an impossible struggle and inherently joyful. Teaching is both rewarding and exasperating. And so the challenge becomes how can I move into the space between hot mess soup and the best school year ever? Instead of burying my head in the sand until June, how can I embrace my responsibilities while navigating the absurdity of this school year?

I’m not running away from my responsibilities. I’m running to them.

Yossarian, Catch-22

Absurd Hero

In Albert Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus, he ends with the famous quote,

I leave Sisyphus at the foot of that mountain . . . Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of the night-filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

Camus presents Sisyphus, not as a nihilist, but as one who, despite the absurdities of his circumstances, continues to create value. Sisyphus makes the best of a bad situation, and in that effort, discovers happiness. Camus’ essay shows us that absurdity is no cause for despair; instead, confronting the absurdity of one’s circumstances allows you to lead an authentic life. So, we should not pity Sisyphus, but admire his lucid tenacity. He knows that forever rolling a boulder up a hill is ridiculous, yet, he finds freedom in that struggle. This is what Camus refers to as metaphysical rebellion: the refusal to surrender to absurdity through despair, but living with and despite one’s absurd fate. If Sisyphus can be happy in such a nihilistic situation, perhaps I, too, can choose to be an absurd hero for the remainder of this year, teaching passionately and authentically through revolt, freedom, and passion.

Turning to Dickens for Help

I may not know how this school year will end, but if I have learned anything from reading Dickens, it is that there is usefulness in seemingly useless things, and one can be happy despite severe hardship. In Charles Dickens’ Hard Times, Dickens uses the juxtaposition between Mr. Gradgrind and Sissy Jupe to show readers that concrete, useful facts ultimately prove useless in the abstract real world. In Coketown, Gradgrind oversees a school where instructors, under his directive, drill students with facts as the sole curriculum, famously opening the novel with the declaration,

Now, what I want is, Facts... Plant nothing else, and root out everything else.

Gradgrind even raises his own children using the same philosophy, prioritizing measurable utility and economic efficiency over the welfare of his children.

Sissy, the daughter of a circus performer, comes to live with Gradgrind and his family. Dickens uses her character to represent imagination and love, which is an especially stark comparison given the bleakness of the industrial factories in Coketown.

Gradgrind’s utilitarian education may see extreme, but teaching in 2025 means enduring standardization and reducing students to quantifiable data points. Rereading Hard Times, I am reminded that I have a moral responsibility to preserve my students’ humanity, and so, I take inspiration from nonconformist Sissy, and balance “Facts” with “Fancy” in my classroom. Any chance I get, I add levity to the school day. This looks like blasting Michael Jackson’s Thriller while we dance and clean the classroom or watching one of my favorite Laurel and Hardy shorts during snack time. I still take my students on a walk around the school building because, as Austin Kleon says, “demons hate fresh air.” Instead of using the prescribed personal narrative example given to students before writing their own, I recreate a live storytelling event like The Moth Story Slam, and tell my own harrowing catfish story.

It may not seem like much, but a little human “Fancy” goes a long way.

I am not expecting this school year to have a perfect “happily ever after” ending. Dickens ends Hard Times with Gradgrind having a change of heart, but I’m not expecting the standardized school system to change any time soon. In my reality, this school year will end with standardized tests and a continuation ceremony. In Catch-22, Yossarian escapes absurdity by deserting and fleeing to Sweden. I am not going anywhere. My responsibilities lie with my students, not with the system. If I must remain simmering in this hot mess soup, I plan to keep making small moments of joy. Because that is what teachers do.

Have a great week!

— Adrian

Resources

What Happened to the Common Core? | Harvard Graduate School of Education

This article by the Harvard Graduate School of Education is a lengthy read, but offers an interesting look at the Common Core Initiative, just four years into implementation. In hindsight, it’s clear that public education has always suffered from the same problems: inadequate funding and lack of teacher support.

Vent Diagrams is a collaborative social media and art project started by educator E.M./Elana Eisen-Markowitz and artist Rachel Schragis. This website has excellent examples

Defending Public Education | American Federation of Teachers

I appreciate the suggestions offered here by Randi Weingarten, president of the AFT. However, as a classroom teachers, strategies like “Revive and Restore the Teaching Profession” are big and unlikely to happen in my lifetime. However, AFT does a good job of outlining the current state of affairs for public education.

Why Transforming Public Education Is So Damn Hard | Andy Calkins, NGLC

The Next Generation Learning Challenges (NGLC) is a non-profit initiative, backed by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, that supports educators in reimagining K-12 public education using technology and innovative models, focusing on personalized, student-centered learning for college and career readiness. If you are a systems thinker, this article is for you. Why do we fail to see the system we are living in? The answer might surprise you!

You can also check out NGLCs most urgent challenges in public education.

Albert Camus on Rebelling against Life’s Absurdity

Philosophy Break is a website and app that seeks to make philosophical topics more accessible. Personally, I prefer Jared Henderson’s Substack Commonplace Philosophy, however, I did enjoy this article by Jack Maden on Camus and rebellion.

John says, Be in relationship with other people and pay attention. Hank says, If I can cultivate interest. If I can cultivate curiosity. That’s enough for me. When reflecting on the absurdity of this school year, it’s easy to go down the what’s the meaning of life rabbit hole. Leave it to Hank and John Green to counter nihilism with such levity. I love this video! It’s hilarious and deeply insightful.

Just a quick TED-Ed PSA for why you should read Charles Dickens.

If you are looking for something more thorough (and more convincing), read Henry Oliver’s post about Dickens’ Bleak House.

Never forget that one moment of joy circumvents so much gradgrinding. You are the teacher who told me in 7th grade that I was a writer. You encouraged me to think for myself. Teaching is maddening (I love the Catch 22 analogy) and you never know when you turn the switch on in your children’s brains. But you do. I experienced it myself. You really really do. I salute you.

Being stuck in a stressful situation that you are powerless to change is one of the most potent triggers for chronic stress, burnout, and depression. I hope you are able to do things to counteract those outcomes. I am curious, how do your colleagues feel about the 15 Day Challenge?