Discover more from Adrian’s Newsletter

I remember getting my first online notification. I can’t remember what I was doing online. I’m pretty sure I was trying to figure out where Carmen Sandiego was hiding when I heard those three iconic words of the late 90s: You’ve got mail. I don’t remember what my new electronic mail message was, but I remember feeling a jolt of excitement that someone, somewhere was trying to communicate with me.

As a teengager, I loved this new computer technology. I could chat with anyone! At least, that is what I believed. I especially loved commenting in chat rooms where I could hide behind my buddy icon and send my thoughts into the void. It was that sound that I remember most. Whatever I was doing, I was immediately redirected to a new message.

27 years later, notifications are pervasive. We receive notifications on every piece of technology we own. There is something about the seeming immediacy of a notification. Think about when your CHECK ENGINE light turns on. Those bright orange, all-caps letters tells you that you need to check your engine now. You don’t’ want to be stranded on the side of the road because you ignored your car’s alert. Your car is trying to tell you something and you better listen.

I believe that society has been swimming in that sentiment for almost 30 years. Whatever it is, it is trying to tell you something and you need to listen. NOW!

I didn’t realize it as a teenager in the 90s, but I was conditioning myself to always be checking for soon-to-be notifications. Inbox email was the digital equivalent of the physical communication (remember envelopes?) we were all used to before computers. When someone would write you a letter, it would eventually travel to your mailbox where it would sit until you saw that rusted red flag sticking up, letting you know that you’ve got mail. Many of us would check our mailbox every afternoon, but if you forgot for a few days, no big deal; you were in for a pile of letters, bills, and junkmail that accumulated. Maybe it is part of my personality, but I never liked the feeling of letting mail accumulate. Maybe it was because I hoped to win the $1M prize from Publishers Clearing House, but even today, when no one is writing me a letter or sending me money, I check the mailbox every day, looking for something exciting.

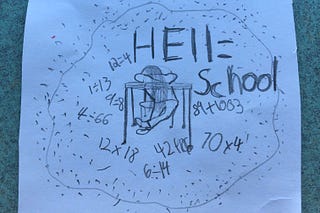

Decades of notifications have had detrimental effects on our society, especially our students. I see this first-hand in my classroom. About 80% of my students own a cellphone and bring it to school every day. This year, I was moved out to a mobile classroom with very little space and no coat or backpack hooks for my fifth-grade students to store their belongings. Students keep their backpacks hanging on their chairs creating a mature, middle school vibe to the classroom. Unfortunately, this means that cellphones are within reach, even if they are in their backpacks.

Dr. Jeanine Turner, author of Being Present, explains from her fifteen years of research, interviews, and experience from teaching students and executives, that putting cellphones in backpacks does not help people be more focused. In fact, the “asynchronous nature of messaging, where we can have emails piling up, texts we need to respond to, we can never be fully present in a conversation” because we are constantly thinking about potential notifications running in the background.

Turner discusses her experiences with college students and executives, but I see the same effects on my ten-year-old students. Even if I make my students put their cellphones away, years of instant notifications and the instant gratification of video games, YouTube, TikTok, and social media, have fundamentally changed how my students interact with with their peers and with me as their teacher.

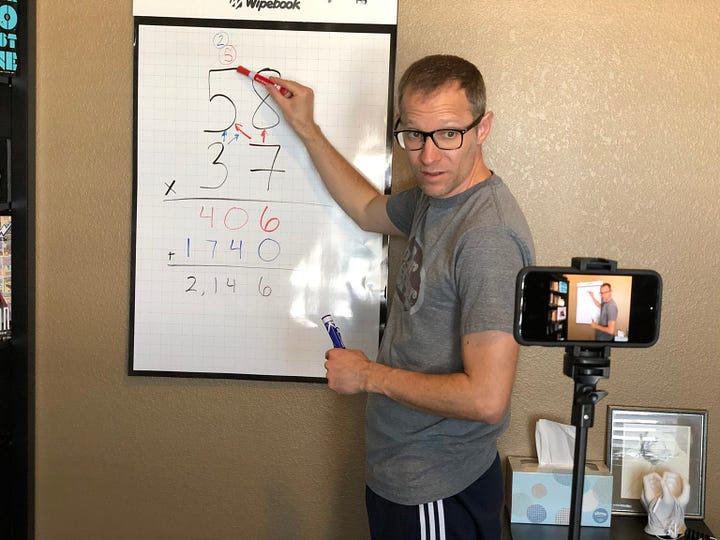

As a teacher, I can’t compete with TikTok. I can’t assume a captive audience anymore. Especially post-pandemic, students have more agency to not pay attention. I am always competing for their attention and losing most days. I’ve limited my “lecturing” to 3-minute directions or interrupting my students with a redirection or an important focus. These feel like commercial breaks that my students ignore. Having a competitive presence in my classroom is not working. I often stop talking and wait for my students to be quiet and feign attentiveness. Oftentimes, it takes 10+ minutes of me waiting impatiently before I can begin teaching again. And then, I’m often interrupted 90 seconds later and have to wait again. This cycle is exhausting. I never feel like I get into a teaching flow, and I’m certain that the quality of my teaching is suffering because of my students’ constant interruptions. It’s like I’m teaching in the background like I did with virtual learning.

Remember virtual learning? I may have been teaching to my students, but with most of them represented as black boxes on my screen, there was no guarantee that they were fully present. In fact, many students admitted to having my lectures and activities play in the background while they were playing Call of Duty.

Students got used to self-selecting what they pay attention to, and it wasn’t school. Today, students are very comfortable choosing what matters to them and where they focus. I can no longer force my students to be present on my terms. Dr. Turner calls this “entitled presence.” A traditional classroom dynamic (i.e.: competitive, strong power dynamic, authoritarian) demands a specific type of student engagement. Many students no longer feel that this type of learning environment is worth their time. They’d rather check to see if their favorite YouTuber has posted any new content. Students know that they are forced to be in school until they are 17 years old, so they treat classroom learning as background music. The teacher is teaching in the background while they are playing Minecraft or texting with their friends. Learning is seen as something they can attune to or disregard as they see fit.

Nostalgic Harangue

Please allow me a brief moment to step onto my soapbox. When I was in elementary school, there were no cellphones. We had a computer lab with bulky desktop computers that we used for typing and playing Oregon Trail. That’s it. I went to school because I had to, but also because I could hang out with my friends. For the most part, I payed attention in school because I didn’t have anything else vying for my attention. I couldn’t watch TV until I got home from school and my homework was complete. I had some intrinsic motivation to learn, but mainly I did so because going to school, paying attention to the teacher, and learning were normalized.

Today, it feels like students have more agency to opt out of school. Couple that with a never-ending pull of their attention and unlimited immediate gratification, it is no wonder that they do not see school as worth their time. Why pay attention to Mr. Neibauer when I can watch MrBeast? Why engage in the learning experience when I can play Minecraft? Why push myself to do something challenging when I don’t want to?

I am struggling to motivate my students to engage with their learning. They don’t have the same intrinsic motivation I assume that I had when I was ten years old. Honestly, if I had been given a choice to go to school or stay home and watch MTV, I probably would have skipped school. Still, I feel like I would have chosen going to school more often than not. Many of my students today are opting out of their learning and choosing from infinite choices of instant gratification. Doing well in elementary school so that you can do well in middle school so that you can be successful in high school so that you can go to college so that you can get a job so that you can be a successful adult is no longer a viable sell to students.

Sell, Sell, Sell

If I can’t compete with TikTok and YouTube influencers, how do I sell myself to my students? How do I convince them that our learning experiences are worth their time?

Dr. Jeanine Turner’s research in social presence offers a useful comparison: competitive space versus invitational space. A classroom that is structured around competition and the teacher’s entitled presence requires the teacher to demand engagement from their students. The teacher talks. Students listen. A classroom that operates as an invitational space is collaborative and flips the teacher-student power dynamic. This type of classroom invites students to co-create what kind of classroom they want to have. It’s a dialogue where everyone contributes and everyone is committed to the learning environment, the learning, the people, and the relationships. Students are more likely to tune into their learning if they are a central part of designing their experiences. Instead of listening to the Mr. Neibauer, 5th grade lecture podcast in the background, they will be more present and engage with those in the classroom. Instead of trying to sell me or my pedagogical practice, I need to sell students on building a classroom community, empathy for their peers, the value of vulnerability, and most importantly, I need to sell students on themselves.

Strengthening Attentional Presence

My students’ ability to be socially present in my classroom requires practice. Years of instant notifications and gratification have atrophied students’ ability to control how they attend to others. In my classroom, I can control the use of technology, being more intentional about how, when, and how much students use it. I can also help my students be more aware of how they are budgeting their attention. If they are reading, are they focusing on the text or paying attention to an extension on their computers? I believe that daily meditation helps my students be more mindful of themselves. It is difficult for a ten-year-old to remain still; harder yet to quiet their mind, letting thoughts, urges, and stressors come and go. Still, this is a practice that, even if I cannot force student to participate in, is a healthy part of our learning environment.

I think that the more I talk with my students about technology, attention, and cultivating a more active social presence in the classroom, will help students make better choices. I only have them for six hours per day, and compared to the other 18 hours (50%+ of which is on their phones), I don’t anticipate any major wins for more engagement in my classroom. No matter the outcome, I want students to understand that learning needs to be in the foreground for it to be effective. I worry that students are fighting an impossible fight for their attention against their phones. Infinite apps never quit; there will always be a new TikTok video, text message, and social media post. I guess we will need to take things one day, 1,000 interruptions, at a time.

Have a great week!

—Adrian

Resources

Do Phones Belong in Schools? - The Harvard Gazette

What happens when a school bans smartphones? A complete transformation

This is just one article of many in a Guardian series about the time we spend on our phones – and how to get it back.

Want help getting off your phone? Sign up to Reclaim your brain: our free email to help you spend less time on your phone

Make Time by Jake Knapp and John Zeratsky

This is a great book (and accompanying newsletter) about optimizing the time you have in your day. I really resonated with the sections on technology distractions.

How Smartphones Have Changed Student Attention, Even When They’re Removed

This EdSurge podcast is where I first learned about Dr. Jeanine Turner’s book, Being Present. This article highlights the key points of the episode.

If you want to listen to Turner discuss her book at length this hour-long webinar is great.

Cellphones in Class are a Disaster - edutopia

I related to many of these 2023 big themes that emerged from edutopia’s comments and conversations, especially the cellphones in class summary.