Discover more from Adrian’s Newsletter

Happy Sunday!

Today, I’m sharing my summary, reflection, and discussion questions for Chapter 2 of

’s Becoming and Everyday Changemaker: Healing and Justice at School. If you missed ’s post last week on Chapter 1: How we move through change matters, you can find it below. Feel free to comment and add to the conversation!In each post, either Marcus or I will provide a brief summary of the week’s chapter, a reflection, and a series of discussion questions designed to spark a conversation in the comments. Feel free to jump in at any point! You can also find our entire fall reading schedule and vision (with links to each chapter’s post, reflection, and discussion) here.

In Chapter 2: Why trauma makes change hard(er), Venet discusses how the collective trauma of the 2020s, including COVID-19 pandemic, Supreme Court rulings, and ongoing racism and violence toward marginalized groups, has affected everyone.

Even if you have not experienced trauma personally, you live in a traumatized society. Collective trauma impacts us all, which means the collective trauma impacts all of our efforts for change (p. 33).

Our communal stress makes change efforts even more challenging since collective trauma effects individuals, communities, and society. Venet then discusses her holistic understanding of how trauma, change, and safety interact. Trauma can influence top-down change efforts from principals and other leaders, as well as teachers’ own efforts to lead from their positions in the classroom.

She concludes the chapter outlining ways that trauma influences our capacity to initiate change in our individual contexts.

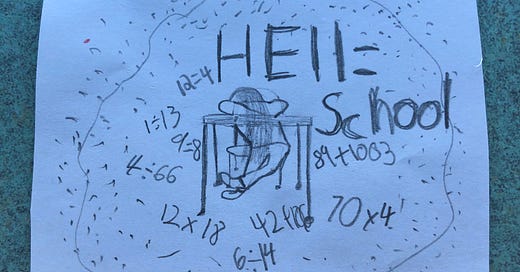

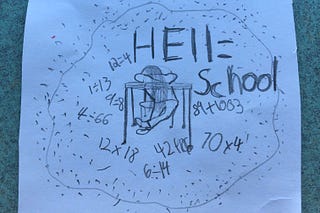

Since returning to the classroom in 2020, I’ve struggled quite a bit with teaching. From the first year back, masking and social distancing, to more recently with remote learning and the subsequent learning loss, I’m not the only teacher struggling to engage students. Every educator I speak with feels like their students are stunted at the social-emotional (and sometimes academic) level of the year they went into lockdown. For example, in many ways, my current fifth-graders act like first-graders in how they interact at school, both academically and socially. Teachers are quick to blame the pandemic, but it wasn’t until I read this chapter that I realized why. We are still living through an era of collective trauma that started in 2020 with COVID-19. Although I am familiar with trauma-informed teaching practices, I didn’t realize that everyone, myself included, has experienced varying levels of traumatic experiences. Understanding these experiences helps explain why teaching and learning (and change efforts) have been so challenging. It’s not just the pandemic. It’s all of it.

I appreciate how Venet discusses change and stress. The term changemaker is often associated with the Silicon Valley bros engineering technology to change the world. However, all change is hard. Change is unsettling. Change can be big, but it can also be personal, local, and immediate. For my students, every Monday is more challenging than the rest of the week. Why? Transitions are hard! While positive stress can aid in learning, when it “overwhelms the resources we use to cope”, it becomes trauma.

Most of the chapter discusses top-down change efforts in public school buildings, such as mandated curricula, staffing changes, and other systemic directives. I felt every word of this section! I’ve sat in countless staff meetings where we are unexpectedly told that we are adopting a new curriculum. Every new initiative is sold as important and must be implemented with fidelity. The problem is that when everything is a priority, nothing is a priority, and the status quo remains unchanged.

These last few years have felt like survival mode. As Venet says “learning is challenging when we are in survival mode” (p. 51). It’s impossible to feel empowered when teachers feel like our agency is taken away. Since 2020, I’ve been expected to implement numerous standardized curricula (including a new social-emotional curriculum like Oriana), seen a redoubled effort to raise standardized test scores, and struggled to engage my students, while trying to heal their past trauma wounds.

No wonder I’m exhausted!

Now it’s your turn!

We highly encourage you to jump into the comments, sharing your reactions, thoughts, questions, anything you’d like about Chapter 2. Remember, the above discussion questions are just a guide. Feel free to share how this chapter resonates with you and your own experiences.

Next week,

from will share his thoughts on Chapter 3: Change opportunities. See you then!

"What would it look like to integrate an understanding of trauma into our change process rather than assuming everyone is entering the process from a place of groundedness and well-being?" (34)

This question from Chapter 2 is what I'm wrestling with this morning. I recognize how so often I've observed and experienced how my own capacity to change as well as those around me felt like it required "being at a good place"—feeling supported and affirmed, being provided with time and resources, etc. Once we "checked those boxes," then myself and others could make the changes necessary.

But reading this chapter, I realize that through a trauma "lens" (34) those boxes are never going to be fully checked—not for any of us. So the process and path to change needs to be available to all of us with our unchecked boxes, too, or else that change is destined to fail. (What that process and path looks like? That's the challenging thing!)